CLOC In Profile - An Amateur Musical Society Run Like A Blue Chip Company

By David Spicer

CLOC began its life in Melbourne as the Cheltenham Light Opera Company, staging The Pirates of Penzance on the smallest of stages in a church hall. Today it is a juggernaut that can make a grand piano dance on stage or simulate a plane crash.

The brains behind CLOC is its president, Grant Alley. A few years back he retired from his day job as a senior executive with Coles Myer. Now he is a full time volunteer.

“We are totally amateur,” says Grant. “Nobody gets paid.”

However CLOC is run with a frightening level of professionalism. They have a 20-year plan and thick organisational charts with detailed job descriptions. Rehearsals are planned with minute-to-minute precision.

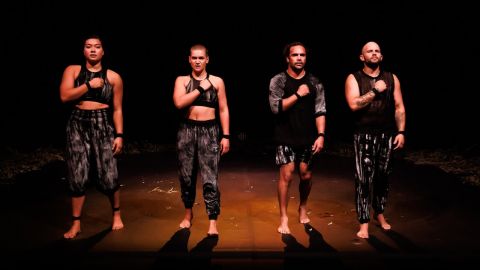

I saw my first CLOC production in May – The Boy From Oz - at their home, the

Alexander Theatre in Monash University.

I couldn’t work out how they made the Grand Piano dance on stage. The 600 kilogram instrument rested on a 30 centimetre high podium. It moved back and forward and sometimes did a spin.

“I pulled apart two electronic wheelchairs,” Grant said with a grin.

“We took an aeroplane radio control and interfaced it into a wheelchair joystick’s controls,” he said. “There is a motor on either side sitting on 4 swivel casters.”

I asked what would happen if they lost control and the grand piano headed for the audience?

“There is a serious magnetic switch all round the edge of it and a metal plate across the front of the stage. If it crosses that point it switches itself off. ”

The driver is backstage and cannot see what is happening on stage, so Grant decided to mount 4 cameras onto the piano.

“It took a controller three weeks to learn how to drive it.”

The designers of the dancing piano also had a plan B and Plan C if it broke down. There was a spare set of controls inside the piano and if that broke too – it could be pushed. As well, CLOC had a second trolley going back and forward across the stage, equipped with an accelerator and brakes.

The lights were special too. There were two staircases – each step had a row of small lights drilled into it. Each step lit individually, in sequence, as the dancers descended to the stage.

It is not surprising with production standards like this that CLOC sells up to 7000 tickets for a season.

So how did it all happen?

“What sets CLOC apart is organisation, administration and infrastructure. Other groups have no continuity - their committee is constantly changing,” said Grant.

Mr. Alley joined the committee in … wait for it …1968. CLOC Administrator Sandra Davies (also a school teacher) has been on the committee for 25 years.

Like any good corporation they even have a self-defence plan against a takeover. Committee members are elected for two-year terms and only half can be turfed out at once. This followed an attempt by some young turks to get elected and take over several years back.

The club became a takeover target when it started to stand out from the crowd in 1983.

“Our big break came when we negotiated directly with Stephen Sondheim to stage the Australian premiere of Sweeney Todd,” he said. “Since then we have only staged contemporary musicals.”

Other non-professional premieres followed: Gypsy (1979), Annie (1985), Evita

(1987), 1776 (1988), Sunday in the Park with George (1992), Song and Dance

(1997), Singin' in the Rain (1998), Steel Pier (2005) and Cats (2006).

Along the way the company has collected 99 Music Theatre Guild Awards.

This year CLOC is staging only Australian written musicals, The Boy From Oz

and Hot Shoe Shuffle, following their 2007 production of another Australian musical, Shout! The next ambition for the company is to premiere an original musical.

The resources the company now has to build sets and make costumes are jaw dropping.

I met Grant inside the CLOC shed. It is the size of a two-storey building, which CLOC built on land leased from a church. The shed is so handy, 20 minutes from the Melbourne CBD, that professional companies rent it for short stints.

Then there is the CLOC wardrobe building, complete with 8000 costumes.

And soon … the official CLOC rehearsal rooms … which they are refurbishing and taking over from a local council.

Volunteers are the heart and soul of the company. Three hundred help out each year. No need for cast working bees when you have a dozen dedicated ladies who come once a week to sew the costumes, and the retired tool makers who also come once a week to build the sets.

Naturally CLOC manages these volunteers in a corporate way.

“We work hard to grow our volunteers,” Grant said.

CLOC appoints mentors to encourage promising newcomers, they have a membership reward scheme accessed by a card, there are certificates for completion of service, and access for volunteers to free cast and crew parties.

Grant admits that the success of his club attracts mutterings from other amateur theatre companies.

"Everyone says CLOC has so much cash. We do well because we produce professional standard productions at a fraction of their cost," he said.

He told me The Boy From Oz set could have cost $150,000 to build, but he did for just 10% of that cost. The secret, Grant says, is ingenuity and persistence.

"It is true that we want to make as much profit as possible to secure our future.

But we also believe in providing affordable entertainment for people who can't afford to see professional theatre," he said.

"And I am always receiving calls from other theatres asking for help with their shows. I always say yes," he said.

With success breeding success, those calls are likely to become more frequent.