The Bald Prima Donna

An iconic play from ‘the theatre of the absurd’, written in 1950, is performed in an iconic, vaguely retro bar in St Kilda. As we wait for the show to begin, we listen to Vera Lynn and Doris Day, a nostalgic touch somewhat at odds with what we have come to see.

A woman perches on a chair in a cheaply furnished but respectable 1950s living room. She talks – and talks – cataloguing what the family had for dinner earlier that evening. She includes a survey of the differing qualities of locally available mayonnaise. It’s rather tedious, but ‘normal’ enough – except that a bare-chested man in a sailor’s cap, her husband, seated in a bathtub mounted on a dais and reading ‘The Spectator’, ignores her.

Strange? Yes, but it’s meant to be strange. It’s meant to make no sense at all. There will be no explanation for the bathtub – or does Mr Smith (for that is his name) have a naval background? It wouldn’t help us if he did. Mr and Mrs Smith expected another couple, the Martins, for dinner, but they didn’t show up. Now they do. Mary the Maid, a traditional (if very glamorous) figure, announces them. The Smiths rush to dress. The Martins, left alone, play an elaborate and repetitious game in which Mrs Martin affects to have no recollection of Mr Martin. The joke wears out its welcome. The Smiths return. Conversation, in which the couples talk past each other and exchange anecdotes of eye-glazing banality, ensues.

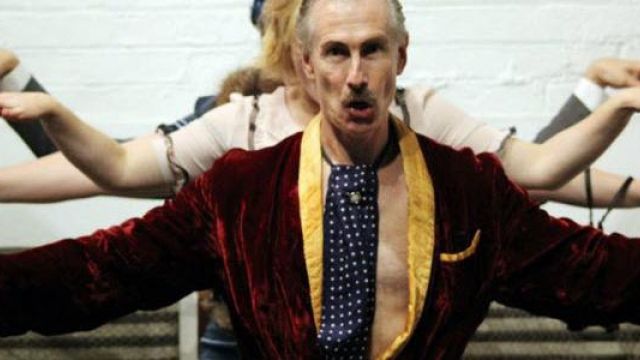

The Captain of the Fire Brigade shows up, dressed to attend a fire. It emerges that he does indeed have a fire to attend, but later. In front of the Smiths and the Martins, he and Mary the Maid exchange passionate kisses and dry hump on the furniture. The Martins and the Smiths appear appalled – perhaps because something has happened. The Smiths drag Mary off-stage and kill her – the first instance of cause and effect, but there is no consequence, of course. The Captain of the Fire Brigade, undeterred, tells long, rambling and pointless stories. Mrs Martin asks what is his point? Of course, there is no point: that is the point. Finally, the Smiths leave. Mrs Martin repeats Mrs Smith’s opening monologue re dinner and mayonnaise.

Such is the play, but Robert Horton and Jane Elizabeth Barry as Mr and Mrs Smith, Alastair Tomkins and Crystal Aarons as Mr and Mrs Martin, Lizzie Ballinger as Mary and Iain Gardiner as the Fire Brigade Captain appear to enjoy themselves and give it all they’ve got. Mr Tomkins is particularly good in the precision of his non-comprehension and weaselly attempts to be liked. The text to the contrary, Mr Martin is almost a character. As is correct for this sort of thing, no one betrays any awareness that what’s happening is ‘absurd’ – that is, no one plays it for laughs – although there were very few in any case.

It is almost painful to see these highly trained actors working so hard on a piece which, however long it stayed in the repertoire, is now dated and verging on trite. No doubt it was for some time ‘shocking’ and ‘funny’ set alongside traditional theatre that attempted to have some point and meaning, but now the general, overall and obvious point is that bourgeois life is meaningless, illogical and repeats itself ad infinitum. Yes – and?

Critic Kenneth Tynan thought that the play demonstrated the impossibility of communication through words. Ionesco vehemently disagreed: he was a writer, he communicated via words. Is the play a satire? Ionesco denied that also: the play is a reflection of reality – a meaningless or ‘absurd’ reality.

As director Heidi Manche says in her program note: ‘If you are looking for plot, a resolution, a linear time unfolding – head back to Hollywood. Real life presents shocks, dreams, regression and a topsy-turvy Rabelais [sic] kind of adventure.’ Leaving aside how pretentious this is (and it gets worse), it also feels just that little bit smug. Yes, the play is iconic, it set a precedent, it’s European, but we are left wondering, why revive this play now?’

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.