Hipbone Sticking Out

Much of the time, Hipbone Sticking Out has a good natured, mocking, teasing surface, but there’s great anger underneath. It is the biggest, most ambitious and no doubt biggest budget production from Big hART to date. Devised by the indigenous community of Roebourne (all named in the program), it is a sprawling, rambling epic narrative, funny, satirical, poignant and angry.

There are beautiful songs in ‘language’ from an on-stage choir, pop songs (‘Paper Moon’ becomes a motif) and even a burst of adapted Gilbert & Sullivan. The multipurpose set can be a screen on which to project rock art, or it is a cave, a ship, a settlers’ hut, a campsite and a gaol. The costumes – some in the brightest colours and dripping with sequins – are allusive rather than real and make pointed comment on characters from the history of the Pilbara up to the present day.

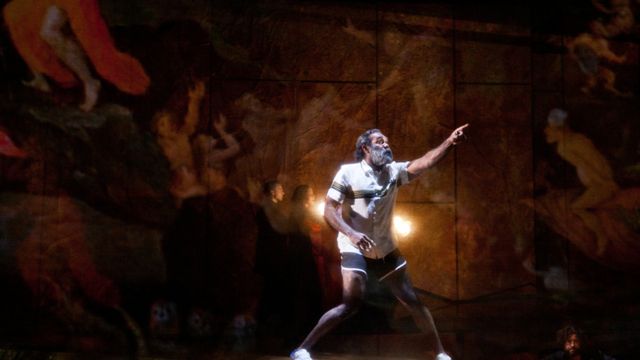

The story begins in 1983 when 16-year-old Yindjibarndi man John Patt lies dying in the Roebourne lockup. It’s a beginning that asks the question, ‘How did we get to this?’ The story then goes back and back one hundred and fifty years and further still, back to the 17th century and the ‘first contact’ between Aboriginal people and Europeans – Dutch sailors in 1606, the better known Dampier in 1688 and on to the arrival of the first white ‘settlers’ at Roebourne in 1863… The narrator is an impatient, wisecracking Pluto, King of the Underworld (Lex Marinos); he’s telling the story to a bewildered spirit John Patt (the wonderful, charismatic Trevor Jamieson), who’s in a sort of limbo, yet to cross the river to Hades. Across the eons of time, the flesh and blood John Patt lies dying…

But the concept doesn’t quite gel. Pluto, King of the Underworld, is amusing, but why drag ancient Greek myths into this story? It’s a nicely pointed irony that Aboriginal culture on this continent is a lot older than ancient Greek myths, but the two make a forced mix. Then there is the show’s mode of mixing history with burlesque – or of portraying history as burlesque. No doubt that’s to sugar a very bitter pill for audiences - but is it also to make telling the history bearable for the tellers?

Sometimes thw anger breaks through and ‘history’ dominates and comes to life – such as the sequence depicting an horrific massacre from the point of view of settlers with a conscience. But at other times, burlesque or ‘satire’ dominates as in the depiction of a rich Dutch merchant father and daughter in which the daughter wears bright pink clogs and the traditional winged hat, and is played by tall Shareena Clanton, clearly an indigenous actor thoroughly enjoying herself. This latter sequence, besides being a bit naff in intention, goes on too long, indicative of a lack of discipline in the writing. Even ‘funny’ needs to make its point and needs to be integrated with its context.

In attempting such an inclusive sweep of history, the show can feel like ‘one damn thing after another’ – that is, a linear narrative without peaks and troughs. Yes, we know where we’re going – we’re building back to John Patt in the lockup – and we can see cause and effect - but there is no dramatic build. That note may be making quite the wrong demand on this show, but I experienced intermittent disengagement: the mash-up of bits of history with the switches in tone, and the mash-up of musical styles created an unproductive distancing rather than contemplation.

In attempting such an inclusive sweep of history, the show can feel like ‘one damn thing after another’ – that is, a linear narrative without peaks and troughs. Yes, we know where we’re going – we’re building back to John Patt in the lockup – and we can see cause and effect - but there is no dramatic build. That note may be making quite the wrong demand on this show, but I experienced intermittent disengagement: the mash-up of bits of history with the switches in tone, and the mash-up of musical styles created an unproductive distancing rather than contemplation.

After an interval, and as we approach 1983 and John Patt’s death, the second half is almost a different show – and deliberately so, according to the program notes. The kick-off is a routine from Mr Jamieson in high heels and hot pants doing a number about ‘indigenous porn’ – the warm inner glow that comes from ‘concern’ about ‘Aboriginal problems’. It’s a routine that may well be mocking a good portion of the audience. After that, things are more spare, more stripped back. Mr Marinos returns, but he wears a coat and tie instead of Pluto’s cape and cowl: he’s simply the narrator.

Now we meet Mavis, John’s mother and with her comes the heartbreaking calls from limbo – the spirit of John Patt calling to his mother to intervene, to save him. ‘Mama… Mama…’ He doesn’t want to die! But he does, of course. This is the death that triggers the Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody.

After this cavalcade of theft, murder, expropriation and exploitation, however, Mr Jamieson tells the audience (twice), ‘This isn’t our story – this is your story.’ I guess he means it is well past time that we white folks acknowledged the story, but it’s not the best way to put it. This history is the Aboriginal story and ours – more’s the pity. Then at the very end, Mr Jamieson, with his gorgeous smile and sublime confidence, says, ‘This isn’t the end – it’s the beginning.’ This – and of course the whole show – got a standing ovation from the audience. It’s a sad but joyful show. It’s community theatre writ large. And it is fundamentally agit-prop. It is also a show that is as much for those who made it as it is for any audience.

By the way, Hipbone Sticking Out is the English translation of Murjuga, the name given by the original custodians for the Burrup Peninsula, which contains the world’s largest outdoor gallery of rock art. A major sponsor is Woodside Petroleum.

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.