The Complete Works of David Williamson

David Williamson - Australia’s most prolific and successful playwright - is calling an end to his remarkable career of 50 years. Martin Portus reviews his legacy.

Note: This article was originally written for the March / April 2020 edition of Stage Whispers, before Covid-19 cut short some of the seasons mentioned.

Williamson wants to go out with a bang and – if he is actually going – the fireworks are certainly aligning. First up, he’s just blown out 78 candles.

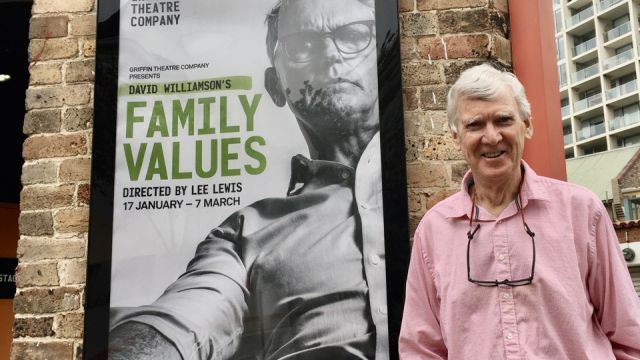

His play, Family Values, with its impassioned call to his generation to become activists against our shameful treatment of refugees, was a big hit this year at Sydney’s Griffin Theatre – and even with those pesky critics who’ve been attacking him for decades. What he calls his last play, his 57th, Crunch Time, which opened at Sydney’s Ensemble in February, is about a businessman seeking reconciliation with his sons and their help to end his own life.

And Williamson’s classic harpooning of Sydney greed and ambition in Emerald City has been revived by director Sam Strong in a QT/MTC co-production. Its costumes and music are straight out of the 1980’s and, says Williamson, there’s nothing dated in the appalling human behaviour.

Williamson – despite carping from leftist or feminist ideologues – is a great believer in the accumulated, essentially unchangeable qualities of what makes us human. A satirist, he says, can’t afford to let wishful ideological fashions get in the way of telling it like it is. The playwright is deeply informed by the post-graduate psychology he studied as he escaped his first short career in mechanical engineering.

“We are far from the perfect creatures that socialist ideology would like to make us into,” he says. “I delight in satirising my own side, that of the pious left – of which I’m still a member – who can often look ridiculous. When I’m asked why I don’t attack the other side, I say they’re beyond satire.”

Now 52 years on from writing a first play at Monash University – and some very crude engineering revues – he likes to think he’s got even better at being a dramatist. But he sounds uncertain; critics have made him defensive about his later work. Mostly only his earlier plays have been revived – like Emerald City, The Club, Travelling North, Sanctuary and The Perfectionist.

“Maybe,” he muses, “I’ve lost the raw energy of The Removalists; maybe I’ve lost the desire to show the darkest aspects of human nature; maybe increasingly I’ve wanted to show the more humane, empathetic, positive sides of human nature but without leaving all the darkness behind.”

“Maybe,” he muses, “I’ve lost the raw energy of The Removalists; maybe I’ve lost the desire to show the darkest aspects of human nature; maybe increasingly I’ve wanted to show the more humane, empathetic, positive sides of human nature but without leaving all the darkness behind.”

As the last line of his ‘last play’ suggests, even after the assisted death, “All is more or less well with the world.”

So Williamson’s problem is only that he’s quite happy – living on Sunshine Beach near Noosa, an enduring marriage, blessed in a blended family of five kids and 14 grandchildren. We know well his long personal journey into the sunshine from his plays, for which over 50 years he’s shamelessly drawn on his own experience of work, first marriages, adultery, fighting parents and generations, cultural clashes, shifting friendships, bitching colleagues and competitive grandparenting, and finally euthanasia … to say nothing of the big social issues he’s plucked from the headlines of our times.

So what now? He’ll walk Sunshine Beach, keep up learning French (a counter he says to dementia), and pound his exercise bike while following podcasts.

Of course he’s retired before, back in 2005, amid even bigger, different fireworks. He was furious at being snubbed by the new directors of the Sydney Theatre Company, Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett. His play Influence, centred on the repellent if sincerely held beliefs of a shock jock modelled on the late Stan Zemanek, had been box office gold for the STC, but Williamson was told they were no longer interested in his work. And the times, he thinks, were demoting the importance of writer.

“Back then I was ditched with this new STC policy of having great actors in great roles,” he says. “And ‘director theatre’ was taking off, with smart kids playing with classics like Chekhov, Ibsen and other masterpieces which surely already had a perfected and proven structure. It was the cult of the director, the cult of Dazzle, and Barrie Kosky, and The Wars of the Roses with constantly falling golden flakes and misplayed guitars.”

A Melbourne journalist back in the 1970s warned Williamson that his first success would be short. ‘The arts is more about fashion than the fashion industry,’ he said, ‘you’ll go out of fashion,’ remembers the Tall Poppy playwright. ‘The only way you’re going to survive is to keep working and keep having people come to your plays because the critical industry will rapidly turn on you.’

"And how true that tuned out to be. I didn’t realise it would happen so fast!”

So Williamson stayed on his toes, changing subjects, being the Living Newspaper of our times. And ever reinventing, he’s always on the quest to find the latest best producer or director, or different state theatre company or alternative to premiere his next work. It’s hard to believe he can retire from this compulsive deal making, as much he can quell that emotional fire about a subject that drives him to the keyboard. Writer’s block was never his problem.

“I wrote Sanctuary (1994) in just ten days, in the white heat of passion and disgust at American foreign policy in Iraq – sometimes the momentum just takes over.”

Back in 2005, a heart arrhythmia condition also called for him to retire. But wounded, he was soon back, writing smaller, more cabaret-like shows and then a host of new plays for Sandra Bates’ Ensemble.

Arguably, Williamson was now serving an aging middle-class audience long comfortable with his comedy and sharing his own older concerns; but he denies that the demographic there on Sydney’s North Shore was any different from his old homes with the state theatre companies.

And true, there was nothing too elderly about his capacity to collar new subjects: ethical challenges to Western medicine, crossdressing footballers, Generation X professionals, Asperger’s, real estate horrors and nightmare grandchildren.

As he’s done before, he can also switch from dark dramas or frothy satires and pull out a philosophical big canvas rabbit, like his recent success, Nearer the Gods. Premiered in Brisbane in 2018, it’s due next year in Sydney. Turning from neighbourhood to the stars, Nearer the Gods is about the discovery of universal gravitation by that eccentric genius, the hero of the Age of Reason, Isaac Newton, and his nurturing colleague, Edmund Halley (he of Halley’s Comet).

“It was one of the biggest leaps by humanity in understanding the cosmos and Newton – difficult, cantankerous, Asperger’s and brilliant – and driven out of madness by Halley to see through the fog of his time.”

Williamson is obviously excited that the story’s internationality has been recognised and director Bruce Beresford is currently in London casting for the film. Of course, Williamson also wrote the screenplay.

And getting up the Newton film redeems all those dud spruiks he did in Los Angeles. His last was for a film of another big canvas play of his, Rupert, in which the global media tycoon tells his epic story direct to the audience. Williamson was unaware, unlike the men across the desk, that a fictionalised version, Succession, and two other related films around Fox executive Roger Ailes were in the works.

“Anyway, Ailes was an American and they still don’t see Murdoch as that, and Ailes had sexual misdemeanours which made him much more interesting than an Adelaide boy starting off with barely nothing.”

Celebrated in the 1980s for his early films like The Year of Living Dangerously, Gallipoli (with director Peter Weir) and Phar Lap, and with film adaptations of ten plays under his belt, Williamson had a reputation overseas as a social issue writer of conscience. As well as significant theatre hits that decade, he had another nice earner writing scripts for Hollywood – but for films never made.

“LA was my least favourite city. I used to break out into a nervous rash on the plane, knowing I had to appear every time before a panel of the director, various producers and studio executives and convince them I was a writer. In Hollywood you always have to act like a writer.”

“LA was my least favourite city. I used to break out into a nervous rash on the plane, knowing I had to appear every time before a panel of the director, various producers and studio executives and convince them I was a writer. In Hollywood you always have to act like a writer.”

Once he got close with a Korean war film he wrote for Jack Nicholson and Tom Cruise, but the head honcho with the final decision thought no one remembers Korea. The precious “green light” wasn’t given. Ultimately, A Few Good Men was the result, but Williamson was long gone.

“Bang. I was suddenly history. No more white limousine. I had to find my own way to the airport.”

Colin, the Sydney screenwriter in Emerald City (premiered in 1987 and a film just a year later) also shares Williamson’s own dream for global opportunities and the quest for that Harbour view.

“But Colin is also passionate about the need to have our own stories in Australia, told in our own accents, otherwise we will always think that real life happens elsewhere and spoken in accents other than our own.”

The Williamsons moved from Melbourne in 1978, attracted, he says, by Sydney’s opportunities, its hedonism and free, less ideological thinking, and the greater professionalism of its theatre and film making. When Emerald City premiered, they moved again, this time to a water frontage…

“My only defence when criticised for that was the Woody Allen defence that any satirist is prey to the impulses he satirises.”

But beyond the Harbour view, telling our own stories in our theatres and films is the driver of David Williamson’s long career. He still gets angry at the memories in Melbourne of how our universities and arts companies were locking out Australian stories and dominated by an English superiority.

“It’s hard for this younger generation to understand the impetus and anger that was burning in our breasts in those days.”

It’s what drove young Williamson to Betty Burstall’s new La Mama and later the Pram Factory in Carlton. He remembers a blokey, fiercely egalitarian and ideological world, more interested in fashionable actor-devised works than writers. They asked him to write the last scene of something so they could improvise the rest; they liked what he wrote, asked him for an earlier scene, and then another.

It’s what drove young Williamson to Betty Burstall’s new La Mama and later the Pram Factory in Carlton. He remembers a blokey, fiercely egalitarian and ideological world, more interested in fashionable actor-devised works than writers. They asked him to write the last scene of something so they could improvise the rest; they liked what he wrote, asked him for an earlier scene, and then another.

“It was the only play I wrote backwards. It was 1970, The Coming of Stork, about blokes in a share household.”

The explosive success of The Removalists and Don’s Party quickly followed in both Melbourne and Sydney. Then Williamson’s next plays, Jugglers Three and What if you Died Tomorrow, were premiered, respectively, by the MTC and the Old Tote at the new Sydney Opera House. He’d arrived, and quickly.

For the next 25 years Williamson was the darling – and cash cow – of any state theatre company lucky enough to get first dibs on his plays. It was his artistic and commercial choice and, for Australian playwriting, his greatest legacy.

“I did transform the local scene and made it acceptable for Australian plays to occupy centre stage in our mainstream theatres, something that hadn’t happened up to this stage. It was always presumed to be British plays or perhaps American or European ones.”

So fierce in 1990 was the competition to premiere his play, Siren, that both Melbourne and Sydney producers grabbed the play, unseen. The Melbourne production opened 15 minutes earlier than Sydney’s, thus claiming the ‘premiere’.

Offstage, notably in Sydney in the 1980s, Williamson was a committed cultural advocate, including 12 years as President of the Writers’ Guild.

And yet … he was dumbfounded when once in a pub, full of writers, one came up to him and said, ‘Williamson, you don’t know how hated you are!’.

The remark is ancient now, but obviously cut Williamson to the core, just like the impact he still shows from old feuds with colleagues and carping with critics.

The giant storyteller to his tribe forged a place for Australian stories on our stages, but then dominated those stages for half a century. Now he’s making room and moving off – perhaps.

David Williamson spoke to Martin Portus for a State Library of NSW oral history project on leaders in the performing arts; the full interview now available on the Library’s website.

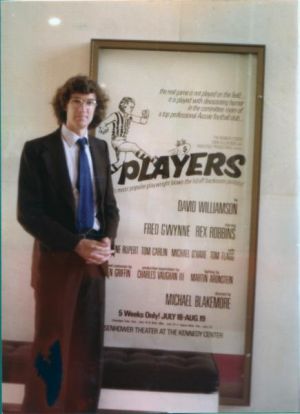

Images: David Williamson at the Stables Theatre in 2020; David Williamson with a poster for Players (as The Club was titled in America): David Williamson outside London's Lyric Theatre during the season of Emerald City; Emerald City in 2020 - Nadine Garner and Jason Klarwein (Photographer: Jeff Busby); Family Values - Andrew McFarlane and Belinda Giblin (Photographer: Brett Boardman); Crunch Time - Diane Craig and John Wood (Photographer: Prudence Upton) & the first reading of Crunch Time.