Theatre’s Poor Cousin: How Circus Fell off the High Wire.

These days Australian circus is a vibrant industry, as typified by the internationally acclaimed Circus Oz, and regular tours from International acts such as Cirque Do Soleil. But this was not always the case. For much of the last century the once prosperous industry was in steep decline. It’s one of the stories uncovered by Mark St Leon in his beautiful new illustrated book, Circus: The Australian Story. Stage Whispers is proud to present this edited extract.

In 1963, 71-year-old Mary Sole, matriarch of the Sole Bros Circus family, complained ‘bitterly’ of ‘Australians’ lack of respect for circus people’.

Doug Ashton, proprietor of Ashton’s Circus in 1971 [endorsed this view]. ‘Australians do not appreciate their circus’. As head of Australia’s oldest circus, Doug described the circus performer as a ‘true artist’, the result of hard work, years of practice, learning how to do one thing really well. There was ‘no trickery, no retakes, no stand-ins’.

In the countries of Europe, performers were ‘looked up to as artists’. Some Australian circus artists, once thought little of at home, were ‘now stars overseas’, but circus artists visiting Australia were puzzled by the Australian public’s attitude to its own circus community.

By 1973, the absence of good, well-trained equestrians, tumblers, acrobats and wirewalkers was obvious. The expectations of Australian circus audiences, once

adjudged the most critical in the world, had become attuned to progressively lower or altered standards of performance.

Between the failed tour of Bud Atkinson’s American Circus & Wild West Show of 1912–13 and the first tour of the Great Moscow Circus in 1965, no complete circus company is known to have visited Australia from overseas. Local audiences were thus deprived of first-hand benchmarks for comparison.

The increasing diversity and sophistication of alternative forms of entertainment, such as cinema (from 1908), radio (from 1923) and television (from 1956), and the weakening attachment of an increasingly motorised people to the horse and horsemanship, contributed to the malaise. On top of these problems was the emergence of animal liberation movements that exposed animal-based circuses to intense media scrutiny. …

What was happening to circus in Australia? Unrelenting urbanisation provides a significant part of the answer. Between 1911 and 1996, the proportion of Australians living in rural areas declined from 43 to 14 percent of the population.

City life provided greater diversity of entertainment for young country people moving to the cities. Looked upon as a ‘low form of entertainment’ and as a ‘poor cousin’ to legitimate theatre by the cultural establishment, many were convinced that the seeming lack of sophistication of the circus would ensure its decline as the world progressed towards higher aesthetic values.

By 1973, there were ‘only four gypsy [sic] caravans’ remaining in Australia — Ashton’s, Sole Bros, Alberto’s and Circus Royale (conducted by the Gassers, a family of Swiss origin and of relatively recent arrival in Australia). Combining, Ashton–Royale was Australia’s largest mainstream circus that year, delivering 270 performances and averaging about 1500 people per performance. Some years later, the proprietors of Alberto’s Circus complained of the burdens of public liability insurance, ground rentals, together with additional costs of power and facilities.

Not helping matters were amendments made to Australia’s Income Tax Assessment Act — ostensibly to stimulate business investment during a period of economic recession in 1974, which thoughtfully excluded the purchase of plant and equipment used in connection with ‘circus, carnival or similar performance’.

In retrospect, the closure of the Silver, Wirth and Bullen circuses, in 1953, 1963 and 1969 respectively, and the fall from public grace of the remaining Australian circus companies, proved to be not so much the end of the genre but the tentative beginnings of a new era in Australian circus. The crisis faced by Australian circus during the 1960s can now be seen as the beginning of a period of adaptation of the institution to changing economic, social and cultural realities. Within a few years, a new, contemporary circus movement emerged, challenging the form and content of conventional circus with approaches informed by the radical arts practice of the late 1960s and 1970s in such areas as the use of performing animals, the nature of training and performance, and the development of performance narratives.

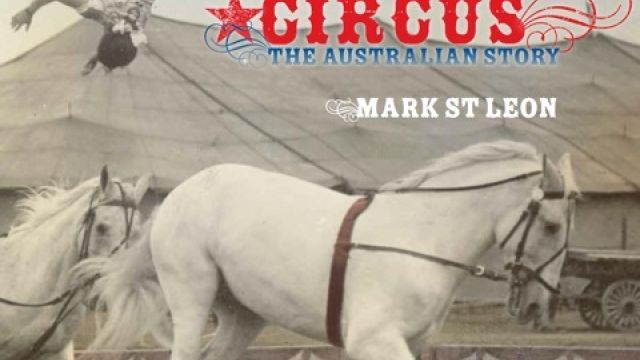

Images: Sydney-born Elsie St Leon (1884-1976), "America's premiere lady bareback rider", photographed in New York, 1908.

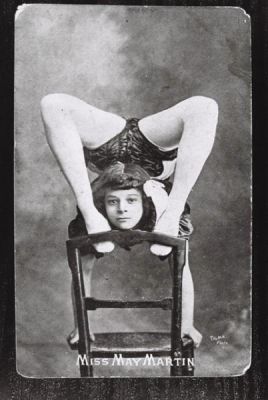

"Miss May Martin, contortionist in Wirth Bros Circus, 1906. Six years later, she made her debut in New York with Barnum & Bailey's 'Greatest Show on Earth' as 'May Wirth, the world's greatest lady bareback rider'. An image of her in action appears on the cover of Circus: The Australian Story, by Mark St Leon."

Order Circus: The Australian Story It is available for $39.95 from bookstores or online at http://www.melbournebooks.com.au/