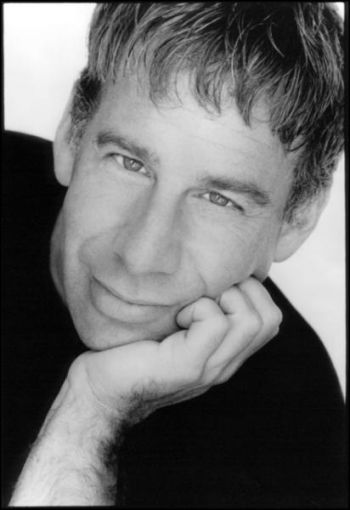

The “Other” Stephen S

Broadway Icon Stephen Schwartz in conversation with Coral Drouyn, during his recent visit to Australia and New Zealand.

For most of his career Stephen Schwartz, composer and lyricist of such smash hits as Wicked, Pippin and Godspell, has had to deal with the “Other Stephen” label in the world of Musical Theatre, dominated for forty years or more by the prolific Mr. Sondheim. Yet if you ask him about it, he simply laughs. “I love Sondheim,” he gushes. “If there had been no Sondheim in Musical Theatre, there probably wouldn’t have been a Schwartz, so any comparison is fine with me.”

I’m supposed to be interviewing this “other” Stephen but the truth is that he is so open and genuinely happy to talk about Musical Theatre, that we quickly find common ground and the interview turns into a conversation. He was in Australia and New Zealand for the Auckland opening of Wicked and a triptych of his works performed in Melbourne by Magnormos.“This new company is just fantastic,” he tells me. “Perhaps the best I have ever seen. The thing about Australian and New Zealand performers is… you all have the most amazing voices. I don’t know why they are different, but they are. Maybe it’s the training, maybe it’s the cleaner air, but vocally the show sounds better. Suzy Mathers is everything I could want in a Glinda, as is Lucy Durack. Sensational singers. You know, in New York someone said that we wouldn’t be able to cast it elsewhere because of the talents and vocal range of Kristin (Chenoweth) and Idina (Menzel) but it hasn’t been a problem; just listen to Jemma Rix. The whole cast brings something fresh to the show.”

Stephen worked for years to get Wicked ready for Broadway – a far cry from his earlier hits, which were written some forty years ago. “I really thought it took just a few weeks to write a musical. The arrogance of youth!” And, in truth, it wasn’t arrogance. Schwartz did write musicals in just a few weeks when he was in his early twenties. But let’s go back to the beginning; it’s always the best place to start a story.

When Stephen was growing up in the comfortable middle-class village of Williston Park in NY State, it was in a time when people knew their neighbours, visited each other’s houses, sang songs around the piano and cherished a sense of community. “It was the early 1950s,” Stephen explained. “My parents would often visit the neighbours, with me in tow. On one side was their friend George…Mr Kleinsinger. Now George was already well known from writing a piece called “Tubby The Tuba” which Danny Kaye recorded. Every kid in America had heard that piece by the 1950s. So George was already a celebrity, though to us he was just a neighbour. When he lived next door he was writing a musical, and he would play us the songs when we visited. When he took a break I would climb up on the piano stool and try to copy, by ear, what he’d played. My parents tried to stop me and tell me it was rude, but George saw something in me and told them, “Let him play, he’s got something, maybe a real musical talent. Don’t ever try to supress it. Better still, get him lessons.”

Stephen’s parents did get him lessons, and he won a scholarship to study at Julliard School of music while at high school.

George Kleinsinger’s musical…. Shinbone Alley (based on the column Archie and Mehitabel, about a cockroach who was a writer, and his best friend, an alley cat) failed on Broadway. “The big question was why would people pay to see singing and dancing cats?” Stephen explains with a gentle gibe towards the incredible success of Cats several decades later. Shinbone Alley does have its place in Musical Theatre history though. “We were invited to go the show. It was one of those moments in life that changes everything. I was, like, eight years old and I knew absolutely I wanted to write musicals. So, thank you George; and he lived to see my work, which he’d inspired, make it to Broadway.”

By the time Stephen got to Carnegie Mellon University he already had a degree in piano and composition from Julliard. “I took drama, with a directing major,” he says. “And of course there was a drama club, as there is for all non-jock Nerds at college.” The drama club was called Scotch and Soda, and each year they did an original musical. No prizes for guessing who co-wrote all three during his three-year degree. “Pippin was actually one of those musicals,” he says. “None of the songs survived in the Broadway version, but it was really a case of taking songs out and replacing them with better ones. I’ve done that a lot over the years. The hardest part is exploring where the songs should be, and what type of song a scene needs.“

Imagine a 21 year old, newly married, Schwartz arriving in New York, hoping to take Broadway by storm, and not knowing where to start. “I wish I could say I suffered for my art,” he chuckles, “but a lot of people had seen the college musicals and I got work playing for backers’ auditions. I guess I made an impression.” Before long Stephen had an agent, Shirley Bernstein, and a job as a music producer at RCA record company. “I guess I have something of a “pop” aesthetic, but hey, I was young, that was the music of my time. Anyway, Shirley tells me that they’re looking for a song for a play in which a blind guy plays a love song. Did I want to submit? Silly question.” That song was Butterflies Are Free, which was used in both the play and the film, and it led to Stephen’s first Broadway musical – Godspell.

Is there any lover of musical theatre who has not seen and loved Godspell? But it didn’t actually start with Stephen. It was a play with a book by Jean-Michael Tebelak, whom Stephen had known from his Uni days. There were a few songs composed by the cast, but it was very much a fringe production by students which had a short run a Café La Mama.

“Edgar Lansbury, Angela Lansbury’s brother, wanted to bring it to Broadway, but knew it needed a rework and a proper score, so he asked me to see it with a view to taking it on,” Stephen recalls. “I said I would try to get there in the following week but he insisted I had to go that night because they wanted to open in six weeks!”

Six weeks to write a complete score? Surely that was unheard of? He agrees. “I didn’t know any better, and there was no way I was going to say no. But I truly didn’t have a clue what I was doing. Somehow it worked and suddenly I was a Broadway composer.” Stephen next found himself as the lyricist of Leonard Bernstein’sMass, thanks to his agent Shirley Bernstein. “She just happened to be Lennie’s sister. Sometimes it really is who you know.”

Pippinfollowed quickly, and again Schwartz had little time, because of Bob Fosse’s availability. Stephen doesn’t openly decry Fosse, but it’s clear it wasn’t an easy time. Stephen was the newcomer….Fosse was God on Broadway. “He changed the ending of the show,” he recalls, “it was litigious, and all over two words. He made the ending dark and without hope. The last line, with Pippin on-stage is “Trapped…but Happy”. He cut “but happy”. I was shocked. It’s not what any of us wanted to say. Fortunately the revival has a new ending and it’s just perfect.”

Then came The Magic Show. “Oh, I had five weeks for that,” Stephen laughs. “It was a commissioned show written especially to showcase illusionist Doug Henning. I don’t think anyone foresaw 2,000 performances on Broadway. There I was at 25 with three of the longest running shows ever on Broadway. Common sense told me it couldn’t last forever.”

When the bubble burst Stephen had a long period of not being able to get things up. It happens to everyone in this business, but it was a new experience for him. “When I left college I had a fallback plan,” he tells me. “I gave myself five years to get something on Broadway. If I failed I would give up altogether and become a psycho-analyst. I’ve always been interested in psychology and I think I would have been happy looking thoughtful and asking ‘How did that make you feel?’ I care much more what people think and feel rather than what they actually do.” I suggest to him that’s maybe why his characters are so strong and his lyrics are driven by emotions. “Yes…I’d say that’s fair,” he concedes. With only limited success with Studs Terkel’s Working (for which he contributed four songs and also directed) and unable to get The Baker’s Wife to work the way he imagined, “Lord knows we tried, but somehow we just missed it. Still, there were some good songs and ‘Meadowlark’ has lived on. You know David Merrick (the producer) hated ‘Meadowlark’ so much that he physically took the music out of the pit so that the orchestra couldn’t play it. Unbelievable.”

Stephen then put several years into Children Of Eden, which is his favourite amongst his shows, but, though it is much loved by Community Theatre, it never found a home on Broadway.

“And suddenly I found fifteen years had passed since the glory days, and I was no longer this “wunderkind” who could turn out a hit in six weeks. I wasn’t sure what I was doing anymore and I said, ‘Okay, I’m finished with Broadway. I’ll never write another Broadway show.’ Famous last words.” He laughs at himself. But he did take a break. Films and television beckoned; he worked with Alan Menken on Pocahontas, winning two Academy Awards. The Hunchback of Notre Dame followed, then the Prince of Egypt, and Pippi Longstocking. “It’s a different world,” he says. “On a stage, you can write a song for someone to sing while being perfectly still. In an animated feature you need a song they can sing while going over a waterfall in a canoe.”

To date Stephen has three Oscars, three Grammys, a Drama Desk Award and six Tony nominations, though he hasn’t yet won a Tony. “Let’s not go there,” he says ruefully. “I was happy doing the movies, and then the television musical Gepetto. I truly meant what I said about Broadway.” So what changed his mind? “I was on holiday with friends in Hawaii, and one said ‘I’m reading this fabulous book called Wicked…It’s about The Wizard of Oz but written from the Wicked Witch’s perspective,’ and lights and bells and whistles went off and I absolutely KNEW it was a musical, and I had to be the one to do it.”

With Stephen re-discovering Broadway as his true home, what’s next? Somehow he’s found time to write an opera and contribute lyrics to Testimony, a Choral Oratorio. “Well, the word has been out for a while that I’ve been working with Hugh Jackman on a musical with Hugh as Houdini. It’s been an insane couple of years with Hugh making three movies at the same time as trying to work with myself and Aaron Sorkin, who was writing the book, until a second series of Newsroom got in the way. So now we have to sit down and rework the timeframe and see if we can really commit to getting this happening over the next two years. If we can’t, then we move on. It doesn’t always work out the way we hope.”

Regardless of what happens, Stephen will return next year when Wicked returns to Melbourne. “It’s wonderful to have an excuse to come to Melbourne. I love it here, and Adam Guettel (The Light in The Piazza) gave me a list of truly great restaurants I still have to try. So I will be here at every excuse.” Somehow you know he means it. He’s just that kind of guy.

Click here to read Part 2 of Coral's interview with Stephen Schwartz, including more insights into his music, how he wrote Wicked’s hit song “For Good”, his solo recording career and what he thinks of current musicals in Part Two in the January / February 2014 edition of Stage Whispers.

Image: Stephen Schwartz with Suzie Mathers (Glinda) and Jemma Rix (Elphaba) during the New Zealand season of Wicked.

More reading

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.