Happy Days

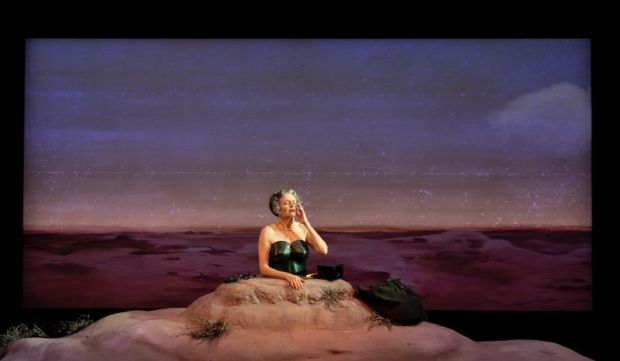

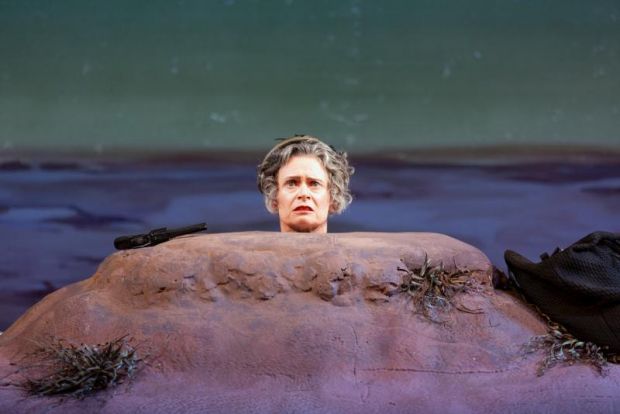

Winnie is woman ‘about 50’, buried up to her waist in a mound of earth. She is awoken by a harsh bell whereupon she begins her daily routines, beginning with a prayer. She drinks the last of her medicine. Her toothbrush has lost its bristles. Despite this predicament, to which she scarcely refers, Winnie is relentlessly, absurdly upbeat. ‘Oh, this is a happy day,’ she repeats. But she corrects, ‘This will have been another happy day. After all. So far.’ She wears a glamorous evening dress to which she will later add a hat. Beside her is a bag that contains all she has, including a revolver.

Fans of Judith Lucy may be surprised – or even shocked. We are used to seeing her as a survivor, certainly, but downbeat, acerbic, ironic and common-sense-cynical. As Winnie, the determined optimist, Judith Lucy could not be more different – and she plays this role brilliantly.

She uses her face as much as her voice – with flickering smiles of amusement at Winnie’s own jokes, at her desperation for a response, for the wan hope that she might ‘float up into the blue… perhaps someday the earth will yield and let me go…’ She gets the apparently random rhythm of the text where one cliché seems to follow the one before.

Yes, there’s been direction from Petra Kalive and voice and text coach Amy Hume, but Lucy doesn’t miss a trick. Winnie may prattle on – and on – but Lucy lets us know where Winnie is coming from as she keeps despair at bay, as she slowly dies. Lucy’s inside the text: every joke, every inuendo – salacious or otherwise – every subversive cultural quotation, every plea to Willie for attention, every regret…

The light is unrelentingly harsh. Behind her, on a cyclorama, a treeless desert vista stretches away to the horizon under a hot shimmering sky across which, during all of Act I, a single small cloud (a sign of hope?) moves left to right until it disappears. In Act II, things generally are worse. The bizarre setting is designed by Eugyeene Teh, following Beckett’s customary directions. The harsh light and the feel of heat (so hot that Winnie’s umbrella will catch fire) is the work of Paul Lim. These effects are so evocative and exactly judged that we almost forget how depressing this setting is. How hopeless, how unendurable. But Winnie endures. J David Franzke gives us the subtle music, but also the ugly sounds that break in and keep Winnie awake – and therefore talking.

No matter what, Winnie keeps to her rituals and her chatterbox monologue, occasionally directing a remark or a question to Willie (Hayden Spencer), her porcine husband. We glimpse him below on the slope of the mound behind her, wearing that (now dated) English seaside knotted handkerchief and a straw boater. He rarely answers, except to grunt or blurt a phrase from his newspaper. At one point, he sings, but refuses an encore. We may gather that once he and Winnie were ‘happy’ but, although they can exchange smutty jokes, their sex life was less than satisfactory. When awareness of any aspect of reality becomes unavoidable, Winnie will squirm past that, shrugging it off with, ‘Ah, what does it matter?’

It's clear that Winnie had a life before this, but she never questions how she got into this mound into which she is slowly sinking. Of course, we may question it, but how or why is not the point. She is where she is now – and that is the metaphor of her fate.

At the first London production in 1962, Kenneth Tynan – a Beckett supporter – wrote that the play is ‘a metaphor extended beyond its capacity.’ As a play per se, I have to agree. We might feel, ‘Okay, we get it. And…?’ Yes, there is development of a sort, and there are many reveals, but it is at times emotionally repetitious – and quite tedious despite Beckett’s sly or broad comedy, his verbal dexterity, his understanding of what some humans will do, say or feel when trapped, sinking, slowly dying and fighting off despair. But at least Vladimir and Estragon have each other, and Krapp regrets and is angry. With Beckett, I feel with some of his work, ‘Come on, Samuel, we know life is meaningless and we know we are evasive about that.’ But we also act, we do things – like he did himself with the Resistance in occupied France.

Nevertheless, a string of prestigious actresses – since 1961 to the present - have played Winnie, undaunted by what amounts to a ninety-five-minute monologue. Just some of them: Brenda Bruce, Peggy Ashcroft, Jessica Tandy, Billie Whitelaw, Irene Worth, Felicity Kendall, Fiona Shaw, Juliet Stevenson. These are big names. Judith Lucy’s interpretation of Winnie can certainly stand in this company. She’s said that her days of stand-up are over; now she wants to act. On this showing, she could have gone there years ago – but then comedians know how to play the audience.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Pia Johnson

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.