The Pigman’s Lament

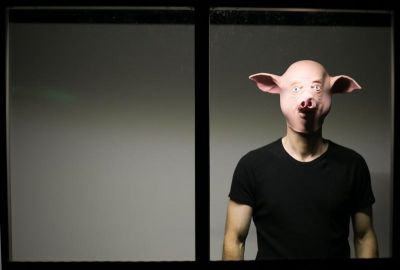

The Pigman’s Lament is an intense, surreal monologue. Raoul Craemer spent part of his childhood in India with an Indian mother, but his father was German, and his grandfather a facist who died on the Russian front. The piece focusses on the grandfather as a secret, almost shameful part of Craemer’s own history.

There is something culturally disturbing about the idea of pig/human hybrids, a theme which recurs in fantasy and horror. Tolkien’s orcs are essentially pig creatures, Doctor Who has had pigs become more human and humans become part pig, and Minecraft has Zombie Pigmen that are docile until you disturb then, after which they attack. Then there’s the sexist pig, greedy pig, lazy pig, dirty pig, schwein hund and long pig. Craemer seems to be saying that the facist in his background is like something awful that he despises and dislikes about himself, likening himself to a pig man. Through the course of the play, the monster becomes more human as Craemer tries to flesh out his character based on what little he knows.

The show is comprised of a series of evocative and frightening yet beautiful nightmarish images, and small, fascinating sub-narratives, which fit together piecemeal rather than as a traditional story. Craemer commands attention, aided by excellent production support. You can see the artistry of director Paul Castro who has a fine visual sensibility in the theatre of the absurd tradition. The design by Christiane Nowak is Dada-esque, with clean white everyday objects on a pristine reflective metallic surface forming an almost forensic setting; fitting for the dissection of a psyche. A window which frames static images or silhouettes sets up character changes through Craemer’s quick footwork and perfectly co-ordinated lighting. Like Paul Castro’s earlier work piece Massacre, the fourth wall is broken with direct audience address, reference to writing the text, and the grandfather character offering judgement on Craemer’s life and of the play itself.

The show is comprised of a series of evocative and frightening yet beautiful nightmarish images, and small, fascinating sub-narratives, which fit together piecemeal rather than as a traditional story. Craemer commands attention, aided by excellent production support. You can see the artistry of director Paul Castro who has a fine visual sensibility in the theatre of the absurd tradition. The design by Christiane Nowak is Dada-esque, with clean white everyday objects on a pristine reflective metallic surface forming an almost forensic setting; fitting for the dissection of a psyche. A window which frames static images or silhouettes sets up character changes through Craemer’s quick footwork and perfectly co-ordinated lighting. Like Paul Castro’s earlier work piece Massacre, the fourth wall is broken with direct audience address, reference to writing the text, and the grandfather character offering judgement on Craemer’s life and of the play itself.

Craemer uses German language on occasion for the poetry and harshness of the language as much as for meaning, but non-German speakers shouldn’t worry that they’ll miss something as much of the German text is repeated in English.

Anyone who enjoys experimental theatre will appreciate the cleverness of this visually stunning piece.

Cathy Bannister

Photographer: Shelly Higgs

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.