In the Solitude of Cotton Fields

A man, known only in the text as the ‘Client’ (Rob Meldrum) goes for a walk… No, he asserts he is walking with a purpose, to a destination, from one place to another, without interest in what lies between. Or, his protestations to the contrary, does his walk have perhaps an entirely different but unadmitted purpose? Somewhere in a city’s dusk, in a lonely place, he encounters the ‘Dealer ‘(Tom Dent), who offers to supply whatever it is the Client wants… The Client claims the Dealer has nothing that he could want or need. Every line here is open to interpretation.

But the Client does not leave; he stays (of course he must) – and he and the Dealer exchange claims and counter-claims, accusations and explanations. They shift in tone and emotion through proud denial, to sales pitch, to aggressive attack and counter-attack, to fear, to wheedling, to rejection… and so to a nihilistic inevitability.

The play and the nuanced, detailed performances of Mr Meldrum and Mr Dent draw out every permutation of a transaction between a buyer in denial and an insistent seller. And yet, here the transaction, such as it is, remains non-specific. We never know what the Dealer has to sell or what the Client may or may not want or need since he admits to neither want nor need – that is, for what the Dealer might supply. Their exchanges are not anchored – or should I say not ‘tethered’? – to any ‘real’ transaction’ between, say, a drug dealer and a respectable middle-class client, or a rent boy peddling his pleasures to a client in denial. An allegory of capitalist commerce? Or the blandishments of consumerism and resistance to them? Or desires that cannot be or are too shameful to be admitted? No. M. Koltès pushes beyond the metaphor of a mere transaction.

Director Richard Murphet anchors this play of ideas in his casting and direction of Mr Dent and Mr Meldrum. Mr Dent is burly, heavily bearded, physically dominating the smaller, quicker Mr Meldrum. Mr Meldrum’s movements – darting away, advancing, cowering – are all finely judged contradictions of his confident speech. These intelligent actors mine the text by their movements, by the clarity with which they point up the key moments of physical contact that the text specifies. Mr Murphet’s mise en scène brings out the instances of fear, pride, evasion, aggression, psycho-sexual undertone and desperation – the last leading to the inevitable final exchange – or what the playwright Bernard-Marie Koltès considers inevitable. It is a pessimistic piece.

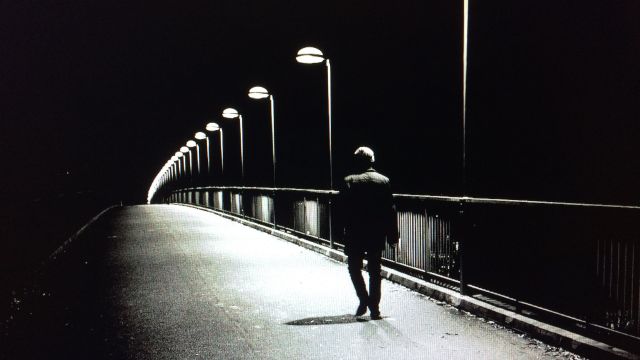

There is no set. A plastic milk crate against a wall is the single naturalistic gesture, but John Collopy’s apparently simple but actually subtle lighting design establishes a setting of urban desolation – a subway pedestrian tunnel or a menacingly dim lit passage by the docks or railway yards, dissolving from dusk to night. Adam Casey’s sound design enhances this uneasy, dangerous milieu, helping the play in (almost) overcoming its resolute non-specificity.

Chatting briefly with Mr Murphet before the show, he remarked – perhaps ironically - that the play is ‘very French’. He is right. It is ‘very French’ in that way of the French love of rhetoric, of disputation, of hair-splitting, of combat by contradiction – and often therefore of clever evasion. Rendered in English, however, there is, unfortunately and despite the skill and conviction of Mr Meldrum and Mr Dent, a feeling of rather forced contrivance, of verbose artificiality. I have at times had the same feeling with the plays of Yasmina Reza – for instance, ‘Art’: very clever and ‘very French’, but it rings not quite true. That is, English- speaking people just would not have these conversations – at least, not this way. But that cannot be held against the playwright.

Nevertheless, In the Solitude of Cotton Fields is a play that, underneath its digressive surface, charts the frailty and pathos of men (women are excluded: in this text, they are mere ‘fiancées’ or the opposite of men). Despite all the words, the play suggests the impossibility of communication, and how that leads to violence. In that respect, what the play has to say is as timely – perhaps suddenly more so – as it ever was.

Michael Brindley

Image by Richard Murphet

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.