Michael Gow's Away Returns

Weather not unlike Sydney’s recent heat wave prevailed in January 1986, when Away opened at Sydney’s Stables Theatre – 37 degrees on opening night, and no air conditioning. “But it still worked, which was gratifying,” playwright Michael Gow told Neil Litchfield.

Three decades after the initial theatrical success of Away, so long a hot property on high school syllabi around the country, the play is having another of its many revivals thanks to a new Malthouse / Sydney Theatre Company co-production. I began my chat with Michael Gow by asking:

Do you ever marvel at the fact that Away has become such a core text in school studies?

I don’t actually. I call it a Trojan Horse for teachers, because they have to study the script, but then they get to drag in Shakespeare, Australian history, social history, and intergenerational themes. So on one level I’m not surprised at all, but at the same time I’m amazed that generations of school kids are tormented by this thing I wrote 30 years ago.

Do you really think the process of studying a play script (not specifically your own) does have that potential to spoil it for students?

From what I hear, Away is slightly different. The teachers that I’ve spoken to over the years said they love teaching it because the kids enjoy reading and studying it. Many of them actually cross the line from just reading it to doing scenes from it, or, indeed, making it the end-of-year show. So, I think it has a performance element built into it. My memories of sitting in a hot classroom, slogging through Antony and Cleopatra are different from the way they’re taught these days, and I think something that’s at least vaguely about the tortures of young people going through adolescence resonates with them anyway, so hopefully it’s not so damaging.

What involvement do you have in the current production?

I went to the first few days rehearsal in Mebourne, then I went back and watched their first few stumble-throughs.

The script, in it’s published form, was a bit rushed after it opened at Griffin, then it was on very shortly after at what was Playbox, now Malthouse, so there’s a few little anomalies which you don’t really notice. But when actors sit down for weeks and weeks and analyse plays, they go, ‘This doesn’t really make sense,’ and I say, ‘No, actually, it should be this.’

So we’ve done that, and we’ve been throwing around a few ideas, just in terms of making things a bit clearer.

You have a lot more stage space with this production. What’s the main difference between presenting the play on a larger stage, as against its more intimate origins?

It’s nice to think you’ve written something that can be that varied – that it can go down to a corner of a room, but it can also have a lot of space around it. That’s what attracts me to theatre – that there’s no definitive version, just this constant reassessment and playing with things, and trying new things. It’s very gratifying that people are still interested in something I wrote 31 years ago, and think it’s worth revisiting.

How has being a prescribed text on the HSC affected the play's success?

It’s been a large part of its success. Because it’s on, and kids are studying it, they therefore go to see it. It’s very popular on the schools end-of-year show list, and it’s also very popular with amateur groups all over the country because it provides lots of roles for people, and the cast can scale up or down according to how many people you want to put in it. When they find out who I am, people will come up to me and say, ‘I was in that play in 1994, when I was at school.’ I think it enters a consciousness if people have had to do it at school, and hopefully had a good time.

It went on to the HSC and the Victorian system very early, then it’s gone on and off ever since. Some books come on, and they go again, but the teachers that I’ve spoken to keep saying that they get so much out of teaching it, and the kids seem to enjoy it. So, as soon as it’s time for it to come back, it does.

The play is set in the 1960s (written in the 80s) but it has universal themes. Could it be reset today or is the 1960s setting crucial?

In a sense it has to stay set in the 60s, because the Vietnam War hangs over the whole thing, but that doesn’t matter. The boy could have died in Afghanistan. I think it’s dangerous to get too into the kind of 60s retro extravaganza, because that can obscure it a bit, so this production goes very gentle on that. The themes are very universal, so it could be set today.

When Richard Wherrett first did it, I remember after the production opened, the men’s cutter in the wardrobe department at the Sydney Theatre Company said to me, ‘You’ve written this fantastic AIDS play.’ Of course ’86 was the middle of the epidemic in Australia, especially in the Arts – the loss was enormous everywhere, and I hadn’t even thought of that. But as soon as he said that, I thought, of course it is. It’s about parents burying their children, and that’s such an awful thing. I think when you know things are definitely going wrong, is where children die first, whether it’s war or anything. So that certainly has an undercurrent of an era that’s not the 60s already going in it.

What inspired the idea of the play’s Shakespearean references?

I started as an actor a long time ago, and I was in a production of King Lear at what was Nimrod. I had a little role and a few walk-ons – I played a character called Oswald, a kind of messenger, who carries letters. It had a great cast – Judy Davis was in it, and Colin Friels, and John Howard and Robert Menzies – and Aubrey Mellor directed it. We played it for a long time – 10 weeks – some of it in the Western Suburbs of Sydney. I sat and listened to this play over and over again, thinking how amazing it was, and wondering how does my little Australian suburban life mesh with this incredible play?

Of course it’s about families, and I sort of started from there. The notion of going on holidays in Australia for the Summer and Christmas is a bit like all those pastoral comedies like As You Like It, Twelfth Night and The Dream, where people leave the city, go into the countryside and go through stuff. That became interesting to me, and I think that’s really where it was born.

It’s also a kind of homage to Patrick White’s play Season at Sarsparilla, which is also about three families, and it’s like those three families from that play go on holiday, and what happens to them. He was such a fore-runner for so many of us playwrights.

That whole idea of the title, of going away for the holidays, is very Australian. So is the play ‘largely autobiographical’, as the Wikipedia entry suggests?

It’s hard to use that word because it tends to mean it’s about your actual literal life, but it’s as much about other people who I knew at the time, or who I now know, who went through things at the time. So it’s not strictly speaking my life on stage, but it’s a kind of compendium of a whole lot of people’s lives of that period.

Away is a text in a HSC topic titled ‘Discovery’. How do you feel it fits into that theme?

The play is largely about denial, so I suppose the process of the play is people discovering what they’ve been suppressing, or ignoring, or refusing to accept.

You’ve actually had a diverse career, so what sparks you to write?

Something that won’t let go I suppose. Writers have ideas all the time, and scribble down things, and they don’t last, or they die, but sometimes there are things that don’t let go, and I suppose that’s what happens.

For the last three years I’ve been working for Opera Australia. I’ve been doing tours of Mozart operas, and writing the English libretto for each of those. That was a huge writing task, so in a sense that’s been a huge output for me. But it doesn’t register in the world as being another play from me, but it’s basically writing three whole plays. I’m not Ayckbourn or anyone like that, pushed to pump out one a year or anything.

I like to keep my earnings abilities within the industry I work in. Many people will take other jobs, or work, say in writing TV, but I’ve never wanted to go there. Yet, I’ve done other things - I’ve directed plays, I’ve run a theatre company – just to keep myself close to theatre. Sometimes you don’t have the energy to write when you’re doing all these other things.

I also like building up pressure, and getting to the point where if I don’t write this play I’ll go mad. Sometimes when it appears you’re doing nothing, you’re actually carrying something around in your head for a long time.

Is it more difficult now for playwrights, particularly with issues like Australia Council cuts?

Probably it is. The difficulty with the big companies is the risk-taking on a new work – the pressure to keep it down to three or four actors is enormous, and that’s kind of boring. I think it’s difficult, too, because there’s this cult of the premiere now. Once if you wrote a play that worked, or even semi-worked, and people paid attention, it would get on in other states and cities. So you got to see your work interpreted by other people, which is always a great learning process. That doesn’t happen now. It’s very rare for an Australian play to get a couple of productions. I think Switzerland is the only one recently that’s been done all over the place.

What do you hope audiences, and in particular students, will take away from the play?

That they come away saying that was great – it’s clear, and fun, and moving, and they were all really good in it - and maybe I’ll go and see something else, if I can afford it.

Originally published in the March / April 2017 edition of Stage Whispers.

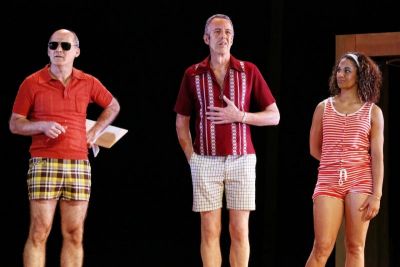

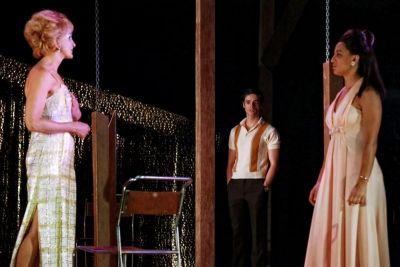

Images from the 2017 Sydney Theatre Company production of Away by Prudence Upton.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.