Appeal of the Bells - The Making of a Dynasty

John Bell’s direction of Bell Shakespeare’s The Tempest in 2015 is a fitting farewell to just one part of his life, and the symbolism of a man who has created magic, abandoning his island for a new life in retirement is lost on no-one. Coral Drouyn looks at the extraordinary Bell dynasty.

For 25 years Bell Shakespeare has been John Bell and Anna Volska’s gift to the nation, and we owe them for that. But we also owe it to this remarkable pair of actors to look beyond Shakespeare, and how and why the Bells can be credited with starting our premiere stage drama dynasty. Anna Volska is a stunning actor in her own right, Lucy Bell is likewise one of the country’s finest actresses, and Hilary Bell is one of our most prominent playwrights, with a third generation now in training at performing arts school to take over the mantle.

John and Anna will no doubt get to see their grandchildren on stage, but John Bell didn’t set out to be the Patriarch of a Dynasty.

It’s not unusual for a boy of 15 nowadays to decide he wants to be an actor, but when you’re 15 and living in a country town like Maitland, and the year is 1955, plus you have the handicap of an awful stutter, it does seem that John took the hardest route possible to a successful career in anything. In those years it was largely considered you had to be a bit of a “Nancy” or a “Flaming Galah gone crackers” to go on the stage…and yes, we did use that kind of language. The cultural cringe was upon us.

It’s not unusual for a boy of 15 nowadays to decide he wants to be an actor, but when you’re 15 and living in a country town like Maitland, and the year is 1955, plus you have the handicap of an awful stutter, it does seem that John took the hardest route possible to a successful career in anything. In those years it was largely considered you had to be a bit of a “Nancy” or a “Flaming Galah gone crackers” to go on the stage…and yes, we did use that kind of language. The cultural cringe was upon us.

Some, including John, would say it still is. But John wasn’t deterred.

“I have always had a love of theatre. I adored pantomime as a child and it has been suggested that sometimes I embrace that style when I play character parts. It’s probably a fair call for comic roles, but I hope the pantomime never becomes parody – it’s the delicious vulgarity of it that won me as a child.”

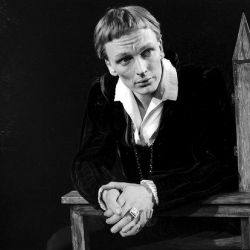

Coming from a strict Catholic family, John was sent to a Marist Brothers College, and it was there that Brother Elgar introduced him to Shakespeare by performing the text out loud, playing all the parts, to the whole class.

“It was an Epiphany,” John remembers, “and I told classmates ‘I’m going to be an actor’ right then and there, and couldn’t be swayed from my conviction.”

By the time John went to University he was alongside such luminaries as Clive James, Germaine Greer and Laurie Oakes, while Film Director Bruce Beresford was his closest friend. Did he think they would rule the world?

“With hindsight I’m sure we thought we WERE the world, and the Universe revolved around us.”

John’s first professional foray was at the Old Tote Theatre, so called because it was in a shed opposite Randwick Racecourse and housed the old, defunct Totalisator machine. This odd place for a theatre also housed the offices for NIDA. When 18-year-old Polish born Anna Volska joined the company to play opposite John as the juveniles in The Cherry Orchard, the future was sealed. Anyone who saw the production (myself included) could see how connected the two were. It was breath-taking

“Call it serendipity or fate…or love at first sight,” John says, “but we both knew even before Opening Night.”

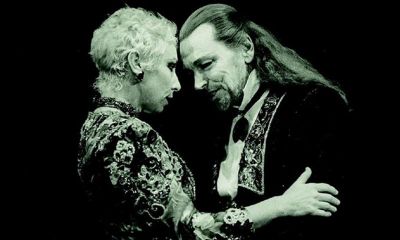

Anna has had a laudable career of her own, in television as well as onstage. She won a Logie award for her portrayal of Helena Rubinstein and was the star of a TV series some will remember called The Godfathers. She’s also proved herself to be a fine director and is currently one of a cast of six of our finest senior actors playing adolescents in Belvoir’s highly regarded production Seventeen (Belvoir previously housed the second incarnation of the Nimrod Theatre, founded by John and Anna, which only changed its name in 1988). Yet, as she grew from teenage years to adult, Anna was content to follow where John felt the need to go. After playing Ophelia to John’s “Too big, over-the-top” Hamlet, she agreed, with their contract over and nothing of interest facing them, to go with him to England to study on a scholarship at the Bristol Old Vic school. That in turn was the door to his five years at the Royal Shakespeare Company, with Anna somehow managing to fit two daughters into a family already full with Shakespeare and theatre.

“I remember Hilary was born in the Digs we were staying in (at Stratford on Avon) and I had to rush back to the theatre for a performance.”

Later Anna would again be Ophelia to John’s Hamlet in 1972, and this time it was for their own theatre, the Nimrod in Sydney.

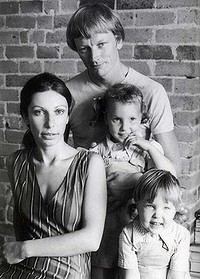

It was the longing for the kids to have a normal Aussie upbringing (“we really did think our childhood was totally normal….though in retrospect…” Hilary says without further explanation) that brought the family back to Australia and to Paddington, where the girls went to school.

“Dad was teaching at NIDA at first, and so I wasn’t really aware of the whole theatre thing,” Hilary recounts. “But we were still very young when they started Nimrod, and I do remember them working ridiculously long hours. We had a silver haired baby- sitter called Sylvia some of the time. But when there was no money, well they had no choice but to take us with them to the theatre. We loved it….beds made up in the stalls or under the dressing table while the tech rehearsals sometimes took all night.”

The Nimrod, in an old stables in Nimrod Street at Kings Cross, started with a brief to present new and contemporary plays.

“It was just a shambles of a place, full of rubbish, smelly, no real ventilation. The seats were planks and there were steps missing. The audience had to bring cushions to sit on. It would never get past health and safety now,” says John.

“Did he tell you there was no toilet backstage?” Hilary quips. “The only outlet was a plastic cup to pee in. Even that seemed totally acceptable.”

Nimrod gained some fame and suddenly the parents of Hilary and Lucy’s school friends were really interested in their parents.

“It was quite a Bohemian existence and money was very tight - we certainly never felt privileged – it was a different kind of notoriety,” Hilary says.

Lucy adds to the story, “I remember being fine with them being actors until my lovely mother had a part on telly in The Restless Years and she had to kiss Dr Bruce. All the kids were teasing me about it the next day and I remember going home upset and angry and confronting poor mum with, ‘Why can’t you be like normal people? They’re laughing at me’. She was mortified.”

John worked so hard in those days making the theatre he started with Uni friend Ken Horler viable, that the two girls welcomed the chance to go to dress runs and performances as a way of seeing more of him.

“They were marvellous, if a little unorthodox, as parents,” Hilary says.

“They weren’t big at imposing their will on us. We were allowed, even encouraged, to explore who we were. But our mother was the most organised person…someone had to be, and Dad’s hands were full trying to keep a roof over our, and the theatre’s, heads,” Lucy explains.

Lucy didn’t realise exactly what acting was until she was five or six.

“It was one of those nights when we didn’t have a sitter and so we went to the theatre with mum and dad. It was Chekhov again – The Seagull - and I was standing in the wings. Dad had exited OP and suddenly I heard 4 or 5 loud gunshots. I remember screaming hysterically,” she recalls.

Was she worried that her Dad was hurt?

“NO….worse than that. I thought he’d killed someone and the police would come and drag him out of the theatre.”

When Nimrod moved in 1974 to the old Cerebos Salt Factory it kept it’s name, and the girls remember amusing themselves behind the bar whilst the show or rehearsals were on.

“We weren’t big enough to reach the alcohol shelves,” Hilary remembers, “but we would make up ‘cocktails’ using cordials or flavouring and any soft drinks, then of course Lucy and I would have ‘tastings’ and sometimes insist our parents try the concoctions. It was a wonderfully bizarre time.”

And it was a time fraught with money troubles and John’s frustration at having to constantly pitch for funding to keep them afloat. Often it seemed they wouldn’t even make the following night’s performance.

John and Anna never encouraged their daughters to pursue normal careers, nor discouraged the theatre as a choice.

“They really wanted us to do what we felt passionate about,” Hilary remembers.

“Though of course, with our background it wasn’t likely that we’d feel passionate about becoming accountants or working in a shop,” Lucy adds.

Hilary knew she couldn’t overcome her shyness to become an actress, especially since her obsession, her passion, was musical theatre.

“It still is,” she tells me. “I’m working on a musical right now.”

At first she thought she might try set designing, but she became involved with Shopfront Theatre in Sydney and that was the impetus for her attending 1985’s Interplay (an international conference for young playwrights). From that point Hilary knew that she wanted to write. Lucy’s path was more secretive. She didn’t want to be labelled as John Bell’s daughter.

“I was very naïve,” she says. “I don’t know how I could have ‘snuck in” to NIDA, after doing a lot of drama at Uni, with no-one recognising me, when the admittance panel had on it friends of my parents who have known me since I was a toddler.” She laughs at the thought. And she actually turned down the chance to work with her father when she graduated in 1991.

“I was very naïve,” she says. “I don’t know how I could have ‘snuck in” to NIDA, after doing a lot of drama at Uni, with no-one recognising me, when the admittance panel had on it friends of my parents who have known me since I was a toddler.” She laughs at the thought. And she actually turned down the chance to work with her father when she graduated in 1991.

“It was too soon,” she says. “I wasn’t ready.”

And by 1990, the senior Bells, only 50 and 45 respectively, weren’t ready to retire, even though John had sworn never to run a theatre company again. When an old Uni friend, Tony Gilbert, said he had some money he’d like to invest in promoting Shakespeare, John was sucked back in.

“I never lost my wonder for Shakespeare; it’s as much a part of me as breathing. The girls were grown and Anna said, ‘yes, we must do this’,” John explains. “And she was with me every step, especially those first few years, when we were in a tent and every week could have been our last.”

The rest is history. Bell Shakespeare is 25, Hilary is an award winning playwright, Anna still a respected actress, Lucy graces our stages and television sets regularly…and John has even directed Lucy in a play by Hilary, and Hilary has written a play for Anna. That’s what makes them a Dynasty, and why Australian theatre owes them so much.

Our writer Coral Drouyn is herself the 4th generation of a Theatrical Dynasty.

Images (from top): Anna Volska and John Bell (Hamlet 1972); Anna Volska and John Bell (Macbeth - 1994); Bell Family (photo Woolfer Peters); a very young Bell Family; John Bell as Hamlet (1962); John Bell as Shylock (1991); John Bell and Anna Volska; and Lucy Bell in The Duchess of Malfi.

Originally published in the September / October 2015 edition of Stage Whispers.