The Convict Theatres of Early Australia 1788-1840

The colourful and surprising history of those who played in Australia’s convict theatres is now published as an Ebook by Currency House. Martin Portus reports that as well as the odd riot and rude thespians there were quality performances and lots of money to be made.

Robert Jordan combed through British and colonial newspapers, official and private correspondence, court records, statistics and logbooks to uncover compelling stories about our first theatrical steps as a penal colony.

And he’s dispelled a few myths already formed around Sydney’s debut production in 1789. The convict staging in a slab hut of Farquhar’s The Recruiting Office was given a fictional treatment in Thomas Keneally’s novel The Playmaker and Timberlake Wertenbaker’s subsequent play, Our Country’s Good. But as in all subsequent convict theatres, the participants actually organised their own theatricals, without guidance from their superiors, and were generally not of the lowest and most uneducated orders.

The first permanent theatre in 1796 sat on Windmill Row, once atop the jumbled, illicit lanes of The Rocks, offering playgoers a sweeping view beyond of Sydney Harbour. It’s now under thirty feet of concrete, buried under the highway approach to the Bridge.

It’s owner/manager Robert Sidaway was a London house-burglar who made himself indispensable and relatively rich as the colony’s first baker, and was pardoned just seven years after arriving on the First Fleet. Indeed, Jordan’s story is full of such convicts who won early opportunities to earn money, including through the theatre, and rapidly went on to be granted full pardons. Sidaway, like many, was originally sentenced to death; he went on to be a publican and noted philanthropist.

Whether in Sydney or Emu Plains, Port Macquarie or Norfolk Island, these convict theatres were established for reasons of educational enlightenment, pecuniary ambition, artistic aspiration or out of just sheer boredom. Only later, after Governor Macquarie left in 1821, were theatres regarded with suspicion as either offering convicts too much respite from proper punishment or leading them further into sin. These moral objections stiffened with the consolidation of a conservative religious establishment in Sydney.

By the time Barnett Levey’s commercial playhouse opened in 1832, it was conditional on him not employing convicts. Jordan quotes the story of a prisoner who was given evening leave from Hyde Park Barracks but who went directly to perform in Levey’s new theatre as Richard III. He was arrested on stage during Richard’s death throes. It could be the tale of the last convict – if not emancipist – to grace our Sydney stages, but it could be fanciful.

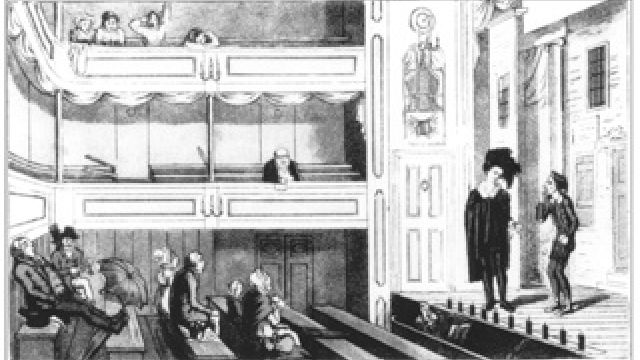

Sydney’s often-fractured elite society were desperate for entertainment but usually kept away from the theatre to avoid the risk of mixing with former or current convicts in the audience. Sidaway’s theatre was, though, relatively smart with front and side boxes for better society, and ticket prices rivalling those of London’s theatres.

And with plays such as She Stoops to Conquer and The Revenge, and standard afterpieces like Bon Ton and Miss in Her Teens, his program too was no more high or low brow than back in London. Indeed, arguably the convict players themselves may have made these choices, and left the audience to enjoy what they got. Decades later, when convicts had left the stage, Australian theatre like in London shifted to less uplifting, more vulgar entertainments, reflecting new audiences everywhere as they now flooded to theatres.

Meanwhile, theatrical careers were made in the colony. Almost no convict arrived here with thespian experience, but Sidaway’s theatre regularly ran benefit nights, denoting considerable status for such chosen actors and bringing them sizable takings.

Meanwhile, theatrical careers were made in the colony. Almost no convict arrived here with thespian experience, but Sidaway’s theatre regularly ran benefit nights, denoting considerable status for such chosen actors and bringing them sizable takings.

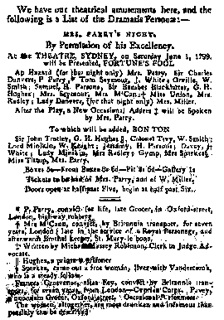

Frances Parry, a fence and probable prostitute in Drury Lane, was the group’s leading lady within a year of her arrival in Sydney in 1798. Like for her fellow performers, her felonies are standard entries under her name on the surviving playbills. Frances married well in Sydney to a grocer-turned-highwayman Philip Barry who, helped by his London connections, inveigled himself into the colonial commissariat as a clerk. By 1800, both were free and on a ship back home.

Sideway lost connection to his theatre well before it closed sometime before 1807. Jordan notes other occasional and charity performances that followed but there is no record of a permanent theatre in Sydney (even under Macquarie) until petitions for one emerge from 1822.

Another sporadic performance was recorded a few years later, when the hit Bombastes Furious was staged in the debtors rooms of the Sydney Gaol.

“Persons of respectability,” said one commentator, “witnessed the rude performance through the iron gratings of the window; their astonishment, no doubt, being excited at the cultivation of the drama being pursued in such a place, and by such persons.”

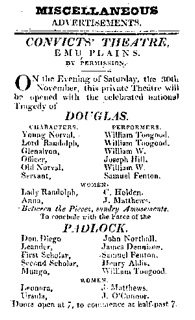

Through the 1820’s a near permanent theatre flourished not in Sydney but beyond, near the Blue Mountains, on a remote convict agricultural station in Emu Plains. Drawing on some 200 convicts, the all-male performance troupe also toured locally to good profit. They were praised especially for their singing and the effectiveness of the costumes and dresses to “trick forth the male performers”.

As at Emu Plains, a belief in theatre’s socialising benefits was behind the encouragement of one at the very end of the world – on lonely Norfolk Island. Here convicts could quickly become settlers holding considerable land, and tensions between them and soldiers often turned nasty. A dispute over seating in the local theatre, a converted granary, broke into a riot and produced a draconian over-reaction back in Sydney from Governor King.

As at Emu Plains, a belief in theatre’s socialising benefits was behind the encouragement of one at the very end of the world – on lonely Norfolk Island. Here convicts could quickly become settlers holding considerable land, and tensions between them and soldiers often turned nasty. A dispute over seating in the local theatre, a converted granary, broke into a riot and produced a draconian over-reaction back in Sydney from Governor King.

Before the theatre was closed in 1794 it housed some of the most colourful names and stories in Jordan’s history. Theatre did return to Norfolk Island forty years later but it was by contrast the province of lesser mortals, often illiterate and low-skilled – just as their audiences too had shifted.

The last energetic convict theatre movement was again in an outlying area, this time in the 1840s at Port Macquarie in northern NSW. James Tucker, after chronicling the Emu Plains theatre, was sent there in 1845, as a second-time convict charged with forgery. Three of his own plays were likely staged at Port Macquarie. Topical afterpieces and small local works had been staged before in convict theatres but Tucker is likely our first fully staged Australian playwright. An epoch was ending already: the official end of transportation to New South Wales came in 1840.

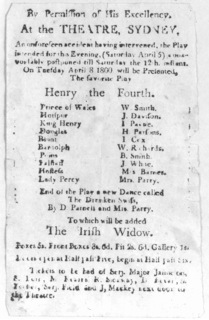

Images: a view of early 19th century provincial British theatre likely similar to the look with boxes of most of the convict theatres; a play bill from Sidaway's Sydney theatre promoting the famed Mrs Barry (with felonies listed, and being a pro in some code); another playbill from same with Mrs Barry featured, and a playbill from Emu Plains clearly calling it Convict Theatre.

Martin Portus is a critic, media strategist and long time director of Currency House.

The Convict Theatres of Early Australia, 1788-1840 by Robert Jordan is available on Amazon, i-tunes, google books and kobobooks in a variety of e-formats.

Originally published in the January / February 2015 edition of Stage Whispers.