Ghosts of Theatre Past

Coral Drouyn looks at myths and traditions that are part of our love of theatre.

Do you believe in ghosts? Even a little bit? Chances are if you have ever stepped upon a stage in a theatre more than 100 years old, you have been watched from the wings by one. Spooky, literally. Melbourne’s Princess Theatre has its own benign ghost - Federici – so popular they named a restaurant after him and keep a seat for him on every opening night. More on Fred later.

The theatre is loaded with superstitions and traditions and we take them for granted now. But where did they start? When you consider that centuries ago actors (or mummers) were gypsies, who were highly superstitious people, it’s not surprising that so many have become theatrical history. There is probably a simple explanation behind them, or maybe not! In this two-part series we’ll look at some of the most famous superstitions in theatre and discover how they travelled from mythology to tradition.

The Ghost Light

There are many stories about Ghost Lights - that single bulb left burning, usually on a pole upstage centre while there is no-one in the theatre. If you’ve ever walked a stage when the theatre is empty, you can feel the ghosts of past actors and actresses around you. Are they just an imprint on the building itself, absorbed personality from dozens of past performers, or does the light attract them to the stages where they once performed? Some say it is a mark of respect to the ghosts themselves. Others say more practically that a total blackout is dangerous and anyone crossing the stage when the theatre is empty could be injured. In fact, that’s exactly what happened in a famous urban legend when a burglar fell into the orchestra pit, broke both legs, and successfully sued the theatre for not providing a safe environment. But it’s just as likely that Actors’ Equity was responsible for the safety measure, so that cast members leaving the theatre late at night would not trip over the set and be injured.

Personally, I prefer the idea that it is for the ghosts themselves, so they don’t feel abandoned in the dark, or even so that they can come out onstage and perform for each other - though I suspect applauding is difficult without solid hands. It’s the most romantic explanation. Whatever the case, the ghost light also symbolises that the theatre is never “dark”, and in these times it’s a great reassurance to all of us theatre-tragics.

Whistling Backstage

It has meant bad luck in the theatre for more than 200 years now. There are tales of mysterious deaths and accidents to the whistlers (and I’m grateful I have never been able to whistle), but can whistling actually bring about your death? Well, in fact, YES, if you look at the origins of the myth. In the 1700s, before theatres had full fly towers operated by flymen, where the stage cloths/scenery could be raised and lowered already unfurled, stage cloths had to be unfurled from the top, 3 metres and more above the stage, and then rolled back up again for every change of scenery. The “riggers” employed to unfurl them were ex-sailors from sailing ships, who were used to climbing masts and unfurling sails by hand. Since they were high in the air on the open sea, the signal they listened for was a whistle. Of course, the method carried over into theatres was the same - when you wanted a cloth lowered you whistled for it. The cloths, heavily weighted along the bottom with a thick wooden batten, would then be freed from above and quite often descend quickly with a loud thud.

So, if anyone was whistling backstage, the whistle could be mistaken for the signal to unfurl and anyone innocently crossing the stage could get their skull cracked open. So yes, whistling means bad luck - but there’s a perfectly logical explanation behind it.

Blue and Green, Seldom Seen

For a long time both colours were considered bad luck on stage - which would have made Wicked impossible to produce. But these two superstitions (my grandmother would never allow blue or green in her dressing room) are based in practicalities.

Blue was the most expensive colour to dye costumes. It’s why you rarely see Old Masters paint with it (Gainsborough’s ‘Blue Boy’ was a sign of the great wealth of the family, and boys wore pink right up until Victorian times), and you hardly ever saw it on stage, producers saving money by perpetuating the myths. In fact, there was another reason. Theatre lights, specifically spotlights, were originally limelights, powered by burning lime. The limelight on the beautiful rich blue made it look more like a muddy khaki, not justifying the money spent. On green, the limelight washed out the colour altogether in the costumes and often only the heads and hands of the actors could be seen - or perhaps the legs of the dancers along with smiling faces.

The sight of disembodied heads and legs certainly did not put bums on seats, so both colours came to be considered bad luck, at least until limelight was obsolete and entire actors who didn’t look like ghosts could be seen from the auditorium.

And speaking of ghosts….

The Theatre Ghost.

Actors’ superstitions may have something to do with an obsession with death. After all, if the audience is unresponsive, we talk about “dying” on stage - or “corpsing” with laughter when we lose control. Every theatre over 100 years old, no matter where in the world it is, claims a theatre ghost, and there is always a story to back up such tales - it’s up to us whether we believe them or not. Having spent most of my life in theatres, I must admit I’d rather be a friend to a ghost than an enemy.

Most ghosts seem to be benign - they just don’t want to leave the theatre (I sympathise) and sometimes they find empathetic performers to show themselves to. Some of them, comedians in this world, are still looking for laughs in their ethereal state - some performers just never know when to get off.

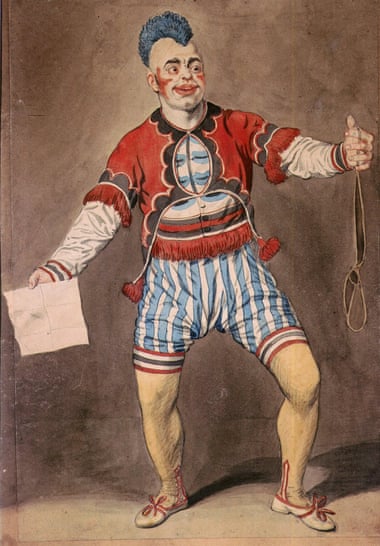

The most haunted theatre in the world is said to be London’s Drury Lane. Two of its most famous ghosts are the clown Grimaldi and the great Music Hall comedian Dan Leno. Though Grimaldi died in 1837, and Leno in 1904, aged 43, the two make frequent return trips to the theatre and have been witnessed by hundreds of people - performers, stage crew, cleaners and audiences alike.

Grimaldi, the first of the great world-famous clowns, had made the strange request that his head be severed from his body before burial, and there have been many reports of a smiling white faced head floating around backstage and even on stage - or perhaps he was just wearing green in the limelight!

Dan Leno’s ghost is most often recognised by the smell. Leno suffered from incontinence and hid the smell with use of an excessive amount of lavender water. It’s not unusual to be on the stage of the Royal and smell a combination of lavender and urine right beside you.

But not all ghosts are performers. Drury Lane’s most frightening ghost is The Man in Grey - a young man with a limp, in a white ruffled shirt and powdered wig, with a grey riding cloak and a tri-corn hat. He is frequently seen crossing from one side of the upper circle to the other and disappearing through the opposite wall. And it’s not at night-time, when such apparitions might be more excusable. It’s always in daylight hours. He has been seen by members of both casts and audiences at matinees, by firemen and theatre managers and crew. In 1939 more than half the cast of The Dancing Years, on stage for a photo call, watched open mouthed as the ghost went about his usual routine.

In the late 1870s, builders uncovered a hidden room behind the wall where the ghost disappeared. There they discovered the skeleton of a young man with a dagger protruding from his ribcage with remnants of grey cloth around the bones. Was the mystery solved - or did it just lead to a greater mystery?

Australia is not to be outdone in the history of theatre ghosts. Adelaide’s Tivoli Theatre (rebranded in 1962 as Her Majesty’s) has a resident ghost in a fly engineer who fell to his death on the opening night of the theatre in 1913. He is said to reappear on opening nights. Ballarat’s splendid Her Majesty’s Theatre boasts several ghosts and even Castlemaine’s theatre has a resident spook.

The Theatre Royal Hobart was actually saved by its resident ghost, an actor who died during a performance in the 1800s, named Fred (a fine name for ghosts). When the theatre caught fire last century, the fire curtain mysteriously fell (for no mechanical reason) preventing Australia’s oldest continuing theatre from being burned to the ground.

But it’s another Fred who rightly claims the honour of being Australia’s most famous theatre ghost, and he can still be found in Melbourne’s Princess Theatre.

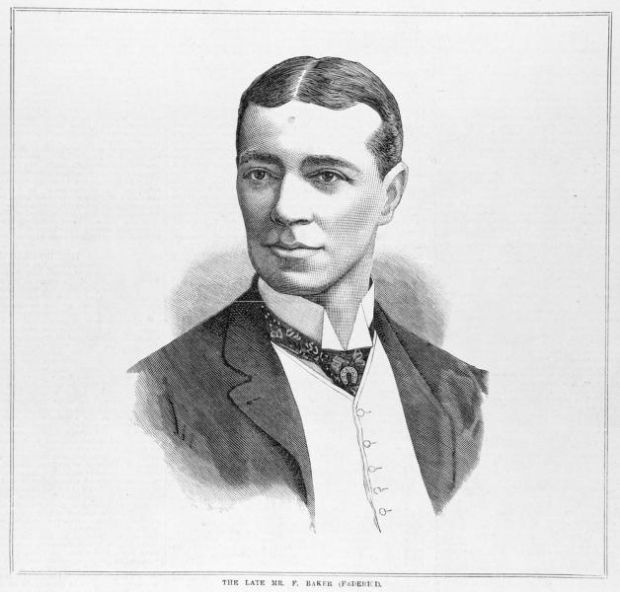

Frederick Baker used the stage name Federici. An Italian/British singer, he’d had considerable success in comic opera in Britain and was brought out by JC Williamson in 1887, appearing successfully in a string of comic operas.

Cast to play Mephistopheles in the opera Faust, opposite Nellie Stewart as Marguerite, on opening night March 3rd 1888, just as Mephistopheles is descending into hell with Faust, Federici suffered a massive heart attack and died within minutes. Although the cast swear that he was in the line-up for the curtain call, as if he returned from the dead to enjoy the applause.

The Press wrote: The tragic and appalling occurrence ... must command universal sympathy and regret. Mr Federici achieved considerable success both in England and America in comic opera, but he was also an excellent musician and the composer of several songs of more than average merit … It seems an act almost of irreverence to criticise the performance of an actor who has only just been carried to his grave. Nevertheless, it is only his due and his proper tribute to say that he both sang and acted on Saturday night in a truly artistic manner and that he has never been seen to greater advantage than he was on that occasion. ... The theatre was closed on Monday evening out of respect to the memory of the deceased artist.

Federici had left his mark on theatre history. It was his third show at the Princess, a theatre he loved so much that he refused to leave. He appears to give his blessings to each production there and the theatre always keeps an opening night seat in the third row of the dress circle. He's a benign presence, and stars like Lisa McCune, Bert Newton, Marina Prior and many ensemble and crew members have had the pleasure of encountering him. That’s an amazing legacy.

Images: Two photos of the ghost light in Sydney's Capitol Theatre in March this year; Grimaldi; Princess Theatre, Melbourne; Frederici.

Thanks to Dru Bartlett of the Victorian Drama League for inspiring this series.

Read Part Two in our October / November 2020 edition, as Coral explores more superstitions, including the long history of “The Scottish Play.” More details here.