Ode to The Tivoli Theatres

A glittering array of Australian theatres once shared the same name. Susan Mills, archivist with the Seaborn, Broughton & Walford Foundation, investigates why just one remains standing, operating as a theatre.

Why is ‘Tivoli’ a seemingly popular name for theatres, worldwide? The name derives from the resort town of Tivoli in Italy, located just outside Rome. Famed for idyllic lush gardens, it consequently became associated with pleasure and entertainment.

The Jardin de Tivoli in Paris, established in 1795, and the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, opened in 1843, are named after Italy’s Tivoli. In London, the Tivoli Beer Garden and Restaurant opened in 1876 on the Strand, to feed audiences of the nearby Adelphi Theatre, and in 1890 became the Tivoli Theatre of Varieties in its own right, a popular music hall venue until its closure in 1914. After World War I, the popular Tivoli Picture Theatre was built on the site.

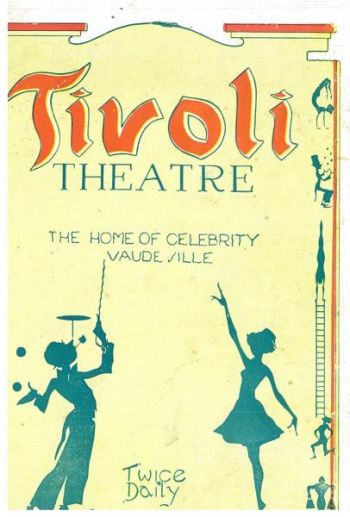

The venue which was to become Australia’s first Tivoli Theatre was built in Sydney in 1890, at 79-83 Castlereagh Street, and was first called the Garrick Theatre. It was in 1893 that Cockney comic singer Harry Rickards took over the lease for his company of vaudeville variety acts and renamed it the Tivoli Theatre. The theatre was bought and subsequently rebuilt by Rickards after being destroyed by fire in 1899.

Rickards’ Tivoli, a Sydney vaudeville fixture until the Great Depression, was briefly bought by all-round entrepreneur Hugh McIntosh in 1928.

It failed to meet structural requirements of having exits into two streets and this, along with the popularity of the talkies, led to its closure in 1929. The building was mostly rebuilt in 1934 by new owners British Cinema Ltd, operating as a cinema, the Embassy Theatre, until its closure in 1977, before its eventual demolition in the 1980s.

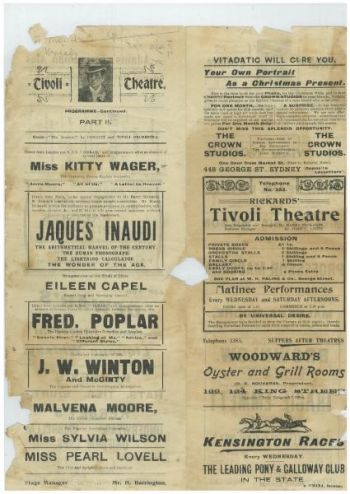

An example of a programme in the Foundation’s archive for Rickards’ Tivoli introduces the vaudeville acts assembled for the week commencing Saturday 31 January 1903. A particular favourite on this bill was the ‘mental calculator’ Jaques Inaudi, an Italian shepherd turned mathematical prodigy with astounding calculation abilities.

The billing for the show explained, “Mr Harry Rickards invites the audience to prepare problems in multiplication, subtraction, division, &c., and Inaudi will give correct solutions without the use of the blackboard.”

The line-up also featured American Comedian Gracie Emmett and her comedy company, English concertina player John ‘Professor’ Maccann (and inventor of the ‘Maccann system’ for this accordion-like musical instrument), Gilbert & Sullivan baritone Wallace Brownlow, and ventriloquist J.W. Winton, accompanied by his droll sidekick McGinty.

The final programme for the original Tivoli is for the last shows, beginning the week of 23 September in 1929. The programme begins with a farewell as the Tivoli prepares to ‘close its doors forever’.

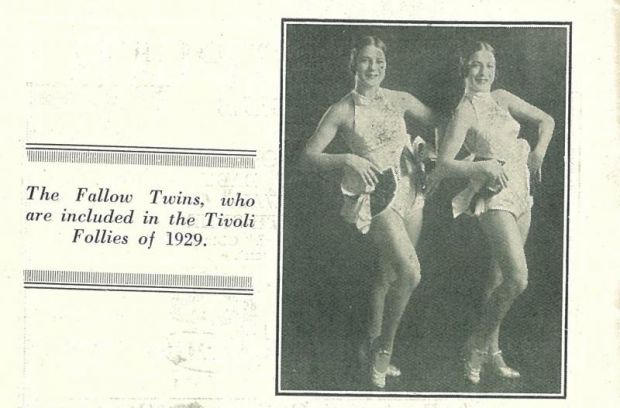

It goes on, ‘No other theatre has such a history. No other theatre is tenanted by ghosts of such talent.” The ‘Tivoli Follies of 1929’ revue included ‘jovial’ Lancashire comedian Jack Edge, dancers ‘The Fallow Twins’, and talkie interludes. Extra special was the appearance each night by Tivoli old time performers in ‘The Tivoli Old Brigade’.

A sidenote about the Tivoli (touring) Circuit, which had grown out of Rickards’ original Tivoli of 1893. After Rickards’ passing in 1911, the lucrative circuit, which also covered Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth, was taken over for £100,000 by sporting entrepreneur Hugh D. McIntosh, then sold three further times, finally to David N Martin in 1944.

In Adelaide, Rickards had leased the Bijou Theatre in King William Street in 1900 and renamed it the Tivoli. In 1913, Rickards’ Tivoli Theatre moved to Grote Street, where the building still stands, now known as Her Majesty’s Theatre. It is the only Tivoli Theatre building still standing and operating as a theatre.

In Bourke Street, Melbourne, Rickards’ New Opera House was renamed the Tivoli when it joined the Tivoli Circuit in 1912 under Hugh D. McIntosh. It eventually closed in 1966.

In Brisbane, the Tivoli Theatre opened across from Brisbane City Hall in Albert Square in 1915, and was converted to cinema in 1927. The building was demolished in 1965. In 1988 another art deco building in Fortitude Valley Brisbane was restored and re-named The Tivoli Theatre. It is still going strong as a concert venue.

What was to become Sydney’s second Tivoli,built as the Adelphi Theatre in 1911 on the same street as the original, this time at 329 Castlereagh Street.

When Benjamin Fuller took over in 1916, he renamed it the Grand Opera House. In 1932, husband and wife entertainers and producers Mike Connors and Queenie Paul and their Con-Paul Theatre company took over management. The theatre was then renamed the New Tivoli Theatre, in honour of Rickards’ original Tivoli.

Opening night on 23 July 1932 featured Roy ‘Mo’ Rene and a cast of entertainers, as well as a blinding £4000 installation of modern neon lighting. In 1934 it became part of the Tivoli Circuit. This Tivoli (the ‘New’ was soon dropped) lasted until its closure and inevitable demolition in 1969.

The last production at the second Tivoli was Hadrian VII, starring Barry Morse, which opened on 23 May 1969. The flyer contains a ‘letter’ from the Director and General Manager of J.C. Williamson Theatres Limited to celebrate the soon to be demolished theatre.

The last production at the second Tivoli was Hadrian VII, starring Barry Morse, which opened on 23 May 1969. The flyer contains a ‘letter’ from the Director and General Manager of J.C. Williamson Theatres Limited to celebrate the soon to be demolished theatre.

“The Sydney Tivoli has had a long and varied history … Margot Fonteyn has danced there; it has twice housed the famous ensemble now known as The Royal Shakespeare Company, and some years ago Laurence Olivier, one of the greatest actors of our age, appeared there with Vivien Leigh…”

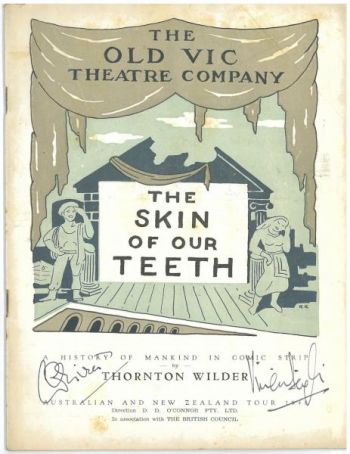

The Old Vic Theatre Company’s tour of Australia for the British Council in 1948, featuring Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier, visited Perth, Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, Brisbane, and Hobart before moving on to New Zealand.

As part of the tour, they played an eight-week season at the Sydney’s Tivoli Theatre, consisting of 18th Century comedy of manners School for Scandal, modern comedy-drama The Skin of Our Teeth (both produced by Olivier), and Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard III.

The season opening night included police herding a crush of onlookers in the foyer, and six curtain calls. Vivien Leigh thanked the audience from the stage, saying “I hope the audience really liked us as much as they seemed to.”