Theatrical Secrets of the Colosseum

On a recent trip to Rome’s Colosseum, Michael Sutton discovered how this world famous icon functioned as a theatre, thanks to a team of German archaeologists. Underground halls were the wings where animals, scenery, performers and Gladiators stood by, and vertical shafts allowed the scenery and talent to rise instantly into the arena.

Built on the site of the tyrant emperor Nero’s former palace, the Colosseum was originally named the Flavian Amphitheatre (Amphitheatrum Flavium) in honour of the Flavian Emperors who built it. Emperor Vespasian started the building to erase all memories of the tyrant Nero. Upon Vespasian’s death in AD79, his son and heir Titus continued the building works and inaugurated it a year later.

When Titus died in AD81 his brother and Vespasian’s youngest son Domitian became Emperor. He made additions to support the workings of the arena, including additional seating capacity in the form of a top gallery.

Estimates of the Colosseum’s seating capacity range from a conservative 50,000 up to a staggering 87,000 people. Even at 50,000 bums on seats, in today’s terms this is one seriously large theatre. There were 76 entrances for the general public and four reserved for the Emperor. Every spectator had a ticket indicating which entrances they had to use and where to sit. The tickets were free but were issued according to social rank. Each spectator reached their own section along a fixed route.As a point of interest to all of us who volunteer or work front of house, they claim they could load-in or empty the entire space in 15 minutes. Try that one in your local community theatre.

Estimates of the Colosseum’s seating capacity range from a conservative 50,000 up to a staggering 87,000 people. Even at 50,000 bums on seats, in today’s terms this is one seriously large theatre. There were 76 entrances for the general public and four reserved for the Emperor. Every spectator had a ticket indicating which entrances they had to use and where to sit. The tickets were free but were issued according to social rank. Each spectator reached their own section along a fixed route.As a point of interest to all of us who volunteer or work front of house, they claim they could load-in or empty the entire space in 15 minutes. Try that one in your local community theatre.

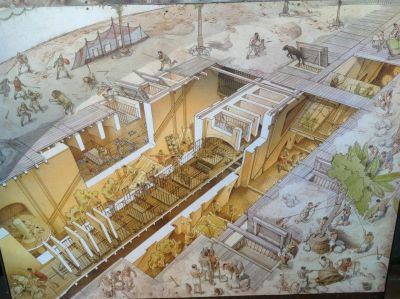

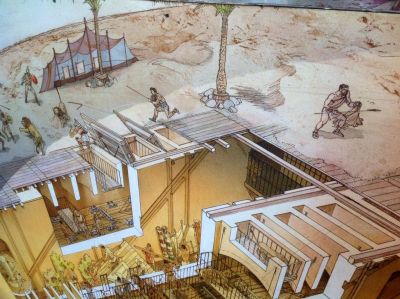

In 1996 a team of archaeologists from the German Archaeological Institute began an investigation into the development and construction of the wooden arena flooring and the mechanisms used to produce staging effects. The design would sit comfortably in most of our venues today.

Eight years of measuring and hypothesizing later, the German archaeologists released a very detailed written report. They shunned the use of modern technology such as laser measuring devices, and computer aided design methods, insisting on crawling all over the place, measuring everything by hand. They touched everything they measured and totally immersed themselves in a tactile experience which they claim gave them a far deeper understanding of the structure and how it functioned.

Today, thanks to their good works, a portion of the floor has been rebuilt and there is a display featuring models of the scenery flying systems. The sophisticated conglomeration of ramps, pulleys and trapdoors, even some of the original counterweights, are on display.

To walk into the Colosseum at any time is a breathtaking experience. For me to walk in, after seeing the displays and reading the background notes on how the venue functioned mechanically, the place all of a sudden jumps to life.

Reading through the original German report is like being in an episode of one of the many CSI type programs on television today. Their deductions, based on the physical evidence and in some cases the lack of evidence, present very compelling reasons why something worked and how.

They pieced together a veritable puzzle, reconstructing a two level network of underground corridors, passageways and tunnels. Some connected to holding areas outside the arena. These underground halls were the wings where the cages of animals, scenery, performers and Gladiators were standing by beneath the arena floor before entering.

Over 28 vertical shafts were identified as locations where the scenery and talent instantly rose, flown into the arena. Contemporary accounts described these entrances as “they appear as if by magic”. Very large capstans operated by trained slaves would supply the power to raise and lower the cages, platforms, scenery and performers on cue. One could only imagine what penalties would have applied for missing a cue or entry.

Larger hinged platforms would drop down allowing a range of animals from lions all the way up to elephants and giraffes to run in on cue.

With the pull of a lever, counterweighted scenery such as artificial forests, even castles made of papier-mâché would raise into the arena.

The Colosseum was obviously far more than what we usually imagine - a blood soaked gladiatorial killing field.

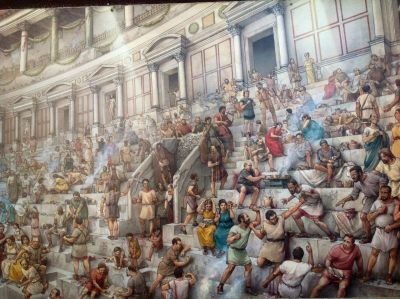

Events often went all day, with the emphasis on spectacular. The day began with a parade called a Pompa, presenting all of the participants. This was followed by hunts called Venationes in which the hunters tackled wild animals lurking among sets replicating the geographical contexts they came from.

During the lunch interval, executions ad bestias took place. The condemned, naked and unarmed, faced the wild beasts which would eventually tear them to pieces. During the intervals there were also performances by jugglers, acrobats and magicians, as well as parodies and re-enactments of ancient myths. Finally in the afternoon, the gladiatorial combats took place. Those who were defeated in a duel could hope to be pardoned by the emperor or by the audience.

During the lunch interval, executions ad bestias took place. The condemned, naked and unarmed, faced the wild beasts which would eventually tear them to pieces. During the intervals there were also performances by jugglers, acrobats and magicians, as well as parodies and re-enactments of ancient myths. Finally in the afternoon, the gladiatorial combats took place. Those who were defeated in a duel could hope to be pardoned by the emperor or by the audience.

Thanks to their popularity the day’s activities were often financed by politicians who hoped to curry favour with the public whereas intellectuals saw these spectacles as a cause of spiritual decadence. Food and drinks were served to spectators at their seats throughout the festivities.

Accounts from that time describe full days of lavish entertainment with a variety of pageants, classical mythology performances and mock sea battles scheduled around the gladiators.

Emperors’ reputations were enhanced by their ability to stage ever bigger, more extravagant and exotic events.

What I really liked about looking at it through theatrical eyes is the fact we can go and look at something made the best part of 2000 years ago, see how it worked and instantly recognize how we do the very same things, using the same bits and pieces or variations of them, in our own venues today.

The problem with having “a visit to the Colosseum” on my bucket list is now - I can hardly wait to get back there.

Originally published in the May / June 2015 edition of Stage Whispers - click here for more details.