Why does diversity matter?

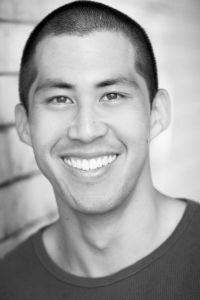

A response to Craig Donnell by Chris Fung

INTRODUCTION

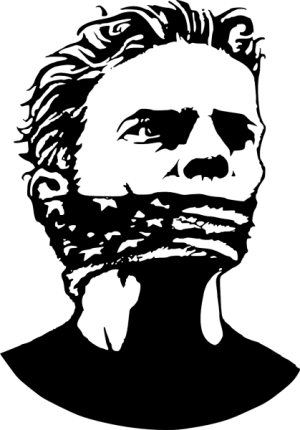

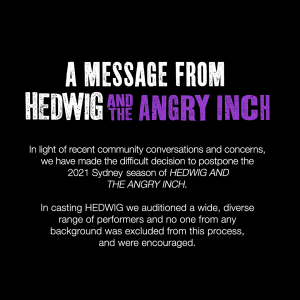

Recently my esteemed colleague, producer Mr. Craig Donnell invited members of the Australian Industry to engage with him on the controversial decision of his peer, Mr David Hawkins, producer for Hedwig and the Angry Inch Australia, to cancel/postpone his show. Mr. Hawkins made this decision after an open letter from the Queer Artist Aliance in Australia was published asking the production to reconsider their casting philosophy in their engagement of non-trans actor Mr. Hugh Sheridan in the title role of ‘Hedwig’ (pictured above) rather than an actor from a trans or non-binary background.

There are many competing viewpoints that are raised by Mr. Donnell’s article. Many of these questions are shared widely by members of the public as well as the industry, and so they are very much legitimate and valid. Reading between the lines lie the questions ‘What is fair criticism?’ and ‘Why can’t any actor play any role?’ and ‘Can cancel-culture advocates go too far?’

It is NOT my intention to provide a definitive answer to these questions, instead it is my intention to objectively outline and present the major arguments for and against these legitimate questions. This is intended to be a one-stop argument outline shop. We might not get there, but that’s okay. If you believe I have made a mistake or overlooked something critical, write in!

I should say that this article is a long one. Many of the questions raised by Mr Donnell are nuanced, and require unpacking. I think that if you are going to answer complex questions, you may as well do it well.

Before we do any of that however, it’s important to acknowledge my personal bias.

BIAS, OWNERSHIP, the RIGHT TO SPEAK

Equity vs Equality. Illustration by Angus Maguire from the INTERACTION INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL CHANGE.

I am biased.

I’m a CIS male performer with a Chinese heritage, born in Australia. I was a member of the Australian touring cast of ‘The King and I’ in 2014 where I understudied New Zealand born baritone Mr. Teddy Tahu Rhodes, where he played The King of Siam, a role that has been central to the debate on diversity in Australia over the past few years, and which was referred to directly, by my esteemed colleague Mr. Donnell.

Personally, I would benefit directly from an industry that provides more opportunity to performers from diverse backgrounds. I am heavily incentivised to influence people towards adopting that viewpoint.

I left Australia in 2018 to pursue performance in the UK, and have since enjoyed consistent professional engagement. My last two shows were nominated for a combined 7 Olivier awards in 2020. I document some of my considerations towards lack of diversity and my decision to leave Australia because of it here.

For me, the current discussion related to trans and non-binary voices and bodies on professional stages, is directly relevant to the marginalisation of all diverse communities, including my own, because philosophically, many of the same arguments apply.

Given these influences, I still intend to provide a balanced accounting.

There are many who believe that ONLY affected diverse voices should speak when contentious issues are raised, many who would say that because I have no background as a trans or non-binary person that I have no right to write an article like this, which on the surface seems to seek leadership of, or to represent the trans or non-binary community.

That is a legitimate and valid criticism, but I believe differently. I think that everyone has the right to speak up when they see something that they disagree with. A big part of that is listening to the central viewpoints and issues raised by key stakeholders. In this case, the trans community.

I should specifically clarify that I do not intend to lead the trans and non-binary community here. There are many well-spoken advocates who are already doing a great job presenting the interests of the trans and non-binary community: the Queer Artists Alliance Australia, Equity Australia to name just two. Instead, I view this article as an attempt to gather and clarify the major arguments surrounding the contentious and vital issue of trans and non-binary and diverse representation in Australian theatre.

CAN ONLY TRANS AND NON-BINARY PEOPLE PLAY TRANS AND NON-BINARY ROLES?

My esteemed colleague Mr. Donnell, wastes no time in getting to the heart of the matter in his article, and neither shall I. However to fully consider this question, we must make a brief detour to discuss some very commonly held misconceptions by debaters on both sides.

There are only two reasons why Diverse Performers are cast professionally: When it is germane to the plot of a show, and when it is not.

Some examples of diverse casting when it is germane to the plot : the African Villagers in The Book of Mormon, Ragtime, Miss Saigon, The King and I etc. Generally these shows are about a specific community group, and in Musical Theatre this is frequently along racial lines. You get African-Americans to play African-Americans, you get LatinX actors to play LatinX roles etc. The heavy inference is that if you do not, you are being culturally insensitive. This is where the outrage for blackface, and cultural appropriation comes from.

Related to this idea is the thought that creatives must have authentic and specific lived experience in order to present a community story well. Why this might be the case, and what the consequences are when this is deemed not to be the case will be discussed slightly later.

In modern times (the past 30 years or so), there has been an explosion of commercially produced works which examine sexuality and gender, and so this idea of germane casting to a show, can be extended to include sexual and gender diversity also.

With Hedwig, it is asserted that the show is fundamentally about the trans and non-binary experience, and thus it is germane to the plot that a specific cultural group, trans and non-binary people, be headlined. My esteemed colleague, Mr. Donnell contests this, and we’ll dive deeper into that a little later also.

Diverse casting when it is not germane to the plot can be defined as any casting where the relation between what an actor looks or sounds like has a negligible impact on the show’s storyline. Maybe the show is not about a particular cultural group or setting. Perhaps it is, and there is widely agreed upon dramaturgical license for the audience to suspend their disbelief. Here is the idea that anyone should be able to play any role.

But does that hold? Can anyone really play any role, or have some cultural groups been excluded from the room?

For the trans and non-binary community specifically, and for this discussion regarding Hedwig, it is argued that there are extraordinarily few professional opportunities for trans and non-binary performers to be cast when being trans and non-binary is germane to the plot, and when it is not germane, those same trans and non-binary performers do not have the same access to opportunity. They cite the much storied and well documented lack of diversity on Australian stages in the last 50 years, and the many layers of gatekeeping that lie between trans and non-binary performers and opportunities in professional theatre. This production of Hedwig, therefore represents a precious opportunity for trans and non-binary performers to be seen, and when the production of Hedwig chooses not to feature a trans and non-binary performer in a fundamentally trans and non-binary role, it perpetuates what is seen to be a systemic exclusion of an entire community group, which is harmful.

To be very specific, there are FIVE issues at stake here which are all readily confused with one another. They are all distinct and separate. It is my intention to clarify this differentiation.

1. Actors can transform.

Can’t anyone play anything? Can’t we use our imaginations to suppose that Mr Sheridan is trans and non-binary? Is that not the craft of the actor? Why is this wrong? Is it germane to the plot that a trans and non-binary actor play Hedwig?

2. Trans and non-binary performers have a significant lack of opportunity.

Do they? Didn’t Mr Sheridan get the role because he was the most talented? Are there really that many trans and non-binary actors of a high enough skill level to take on a job like this? Why is this one role so important? Is it really Mr Donnell’s fault if trans and non-binary actors were considered and if they simply were beaten out because Mr Sheridan was more suitable/talented than other candidates?

3. Even if there is a systemic lack of representation for trans and non-binary people in the arts, what’s the harm?

Is lack of representation or less than accurate representation in one show even relevant? What is more evil, the opportunity for harm, or the cancellation of a contract for an entire company?

4. Do producers have an ethical/moral/legal responsibility to champion diversity?

What is the nature of that responsibility, and how do we measure whether a company has done enough? Is there ever such a thing as ‘enough’?

5. Is it reasonable or unreasonable for trans and non-binary performers to demand representation and opportunity?

What reasonable measures *should* companies adopt towards addressing this and what are the gains?

It is important to reiterate that these are all separate but very closely related concerns. They frequently get intermingled.

IS HEDWIG EVEN A TRANS AND NON-BINARY SPECIFIC ROLE?

Neil Patrick Harris as Hedwig on Broadway. Photo: Joan Marcus

The role of Hedwig has historically been played by a cavalcade of non-trans and non-binary actors. The writer himself has even played the title role as a cis white male. What’s the harm in continuing that tradition? Why is this wrong?

A fair question.

Trans and non-binary advocates have and would say that the show is fundamentally about the trans and non-binary experience, that it is less or completely irrelevant what the writer himself believes, or what the historical precedent has been for actors who have played the role professionally, because what a show means, and how it is received by an audience is something which is dynamic and fluid, and determined by specific audiences in specific places in specific contexts.

The Australian, and indeed global social context is a different world today than even a year prior. Particularly with the advent of social media, stakeholders now have a higher degree of expected public accounting for representation than in any other time in history. The theatrical community today has recognised the harm that lack of representation and opportunity can cause towards a diverse community, and this in turn has given rise to powerful social equality movements.

Mr. Donnell asks ‘Why is casting a non-trans and non-binary actor in a trans and non-binary role wrong?’

It is considered wrong for moral reasons.

It is wrong because enough people believe it wrong. It is wrong because many trans and non-binary advocates equate lack of visibility to an active devaluing of trans and non-binary people. Because lack of visibility perpetuates the idea that trans and non-binary people are not quite good enough, and in the wider community, this can and has led to physical violence, and other, less visible forms of harm. For these reasons, authenticity in casting and in the presentation of trans and non-binary stories is seen as vitally important.

It is important to understand why trans and non-binary advocates think this way, and for the cynical and financially focused, it is important to determine whether this viewpoint is one shared by the audiences that they wish to target.

For the former, there are a lot of researchers in this field specifically who have documented their answers to the above, and I would suggest each person reading determine for themselves whether there is a causal link between lack of opportunity, media portrayal of trans and non-binary people, and violence.

If you’d like to read more:

Solomon, Haley E., and Beth Kurtz-Costes. "Media’s influence on perceptions of trans and non-binary women." Sexuality Research and Social Policy 15.1 (2018): 34-47.

Lester, Paul Martin. "From abomination to indifference: A visual analysis of trans and non-binarygender stereotypes in the media." trans and non-binarygender communication: Histories, trends, and trajectories (2015): 143-154.

Jobe, J. N. (2013). trans and non-binarygender representation in the media.

WHY CAN’T ACTORS TRANSFORM? WHY CAN’T AUDIENCES USE THEIR IMAGINATIONS? CAN ONLY PEOPLE WHO IDENTIFY AS WIZARDS PLAY WIZARDS? SHOULD ONLY PEOPLE FROM SPECIFIC BACKGROUNDS PLAY SPECIFIC ROLES?

Here’s what my esteemed colleague Mr. Donnell has written.

‘If they wrote a musical version of A Beautiful Mind - should the role of John Nash only be portrayed by somebody who has had a lived experience of paranoid schizophrenia?

Should the role of Albin (La Cage) only be portrayed by somebody with drag experience? Should they at least be gay as a minimum?’

I believe that in a Utopian society, all actors should be able to play all roles. I personally have no issue whatsoever with Mr Hugh Sheridan taking on the role of Hedwig, or of Mr. Teddy Tahu Rhodes in taking on the role of the King of Siam, were things ideal. In a Utopian society we should all have the freedom and capacity to make ‘bad’ art, everyone should be able to play all roles, with only a nuanced understanding of what you want to achieve artistically as your guide. Creative companies should be able to cater to whatever audiences they desire. The issue is that we don’t live in that world, and we’ve stumbled upon a context where production companies are looked to to provide moral leadership in their expression of the ideals of equality.

Obviously, we as a culture are capable of the imaginative leaps that allow anyone to play any role. That isn’t the real issue at stake, indeed, I have yet to find any trained performer, who would argue that imagination, and the ability to pretend is not fundamental to the craft of being an actor.

The issue is that we are faced with a systemic, historic and global lack of opportunity for marginalised groups, so lack of diversity in the arts magnifies lack of opportunity in society. Because of that, production companies are now being held to a higher standard when their public decisions infer that particular community groups matter less.

Now is that fair and right?

Diversity is central to social consciousness right now. It makes sense that our art is a reflection of societal values. It makes sense that there is greater opportunity and visibility for traditionally under-represented and marginalised groups right now because of that primacy. Eventually, that will no longer be the case, and when that happens, diversity will no longer be contested, because hopefully, society will no longer see a need to.

‘Should only members of the LGBTQI community play the role of Lola in Kinky Boots? What would happen if a straight man was cast?’

Right now advocates for diversity believe it ethically wrong to cast outside of marginalised community groups when it is germane to the plot. Of course there must be interpretation applied and generally it’s held that so long as sufficient consideration is paid to authenticity (however you determine that), that this rule can bend. Notably, I think that if you are a student, or a non-professional hobbyist, that you can be held to a less prescriptive standard, because students should be able to explore their craft, and because the implications for wider social outreach do not apply the same as they would for professional storying where the outreach is larger, where the implications for highlighting and excluding specific voices is greater.

I will provide my answers to Mr. Donnell’s questions above, though I think it is important to say that it is not my intent to speak on behalf of groups that I do not belong to - to speak on behalf of the LGBTQ+ community in order to pursue an agenda that they may not wish to push.

I base my responses under the philosophy that ideally, everybody should be able to play everything, but these are not ideal times, and it is clear that there are roles which are fundamentally about a particular people, and a particular time, in a particular context. I believe that especially when a community does not have equality of representation and opportunity, that germane roles should be reserved for members of that community.

I would expect a professional actor portraying Mr John Nash from A Beautiful Mind to not necessarily have had Paranoid Schizophrenia but for the portrayal to be respectful. I would expect an actor portraying Albin from La Cage to have drag experience and to have lived experience as a gay person, I would expect only members of the LGBTQI+ community to play the role of Lola in Kinky Boots.

Many gay and lesbian performers have been successfully playing heterosexual roles and vice versa for years so Albin and Lola provide the perfect situation to assess independently. If the LGBTQI+ community feel equality is achieved these roles can be played by anyone. Sexuality is fluid and just because someone is currently in a heteronormative relationship does not mean they have not lived a homosexual experience.

Image: A Wizard. Image: Pendleberryannette via Pixabay

THE JOB OF A PRODUCER

Image: 200degrees via Pixabay

The job description of a commercial producer has remained the same for the past 100 years. To accurately predict/gamble whether a specific financial investment for a particular idea will resonate with a paying audience and produce sales. The only difference being that the stakes for accountability seem so much higher now.

The pertinent question for commercial producers is: if your show is called out for discrimination, what will the effects be on your bottom line? Is ignoring your critics an effective strategy?

We don’t need to look far for a comparable situation. The producers of Pippin, the Gordon Frost Organisation, have recently been called out by Equity Australia for casting an international actor in a role traditionally played by a person of colour, citing a lack of appropriate local diverse talent and for refusing to agree to formal agreements with Equity over artist importation. It isn’t an exact replica of the situation faced by the producers of Hedwig, but there are lots of similarities. Only time will tell if the GFOs decision to make no real adjustments in response to community outcry, will have any impact on their bottom line.

Mr Donnell has a significant work history with Mr John Frost and the Gordon Frost Organisation, having until April 2020 held the post of Executive Producer and Managing Director of the GFO. Mr Donnell’s recent production and co-producing credits include: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Dreamlover and Evita. The GFO has incontestably been one of the most prolific production companies in Australia over the past 30 years, and has therefore faced a large amount of criticism for their role in shaping what is deemed by many critics as a systemic lack of opportunity for diverse performers.

It is important to note that I, and many other advocates for diversity would wish closure on no show. Indeed, the open letter from QAAA didn’t seek closure, they sought greater intellectual rigour and consideration for this and future commercial productions. It was Mr Hawkin’s choice to cancel/postpone his production. I think that that distinction matters.The cancellation of any show, and the loss of work for creatives is always a tragedy.

I hope that Pippin is a success, and that Hedwig is remounted.

‘WHY SHOULD I LISTEN TO COMPLAINTS ANYWAY. WHAT COMPELS ME TO GIVE YOU CREDENCE?’

Legally, except in corner cases, producers have little obligation whatsoever to heed criticism from the wider community. Fundamentally, they can spend their money how they wish, with whomever they wish, being answerable only to their investors and to their paying audiences.

Outside of the last 5 years, it is my observation that Australian producers have proven remarkably aware of this, sometimes making very few changes if any to controversial casting or programming decisions and public outcry. (See: Opera Australia’s contentious commercial success, The King and I in 2014).

If any obligation exists to embrace diversity then, it is a moral and ethical one, where production companies acknowledge a responsibility to model and shape social consciousness for themselves.

Over the past 20 years, a greater custodial responsibility has been thrust upon this industry. There now exists an expectation that arts institutions uphold and reinforce positive societal values.

Today production companies face social pressure in order to embrace that role of moral custodianship. Does the public have the right to impose that? Is it really okay to tell someone else how to think and what they should do?

I think it’s not okay to impose or mandate a way of thinking, but it’s important to advise and to be understood, and we can make the stakes clear for change.

Image: Ear Protection.Clker-Free-Vector-Images via Pixabay

BUT I’M ONLY DOING ONE SHOW, WHY SHOULD THE HISTORIC LACK OF REPRESENTATION IMPACT MY DECISION TO PUT ON THIS ONE SHOW WITH AN ACTOR/TEAM I WISH TO WORK WITH?

My esteemed colleague Mr. Craig Donnell didn’t ask this question, but it is a very reasonable one. Let’s discuss.

My esteemed colleague Mr. Craig Donnell didn’t ask this question, but it is a very reasonable one. Let’s discuss.

Fundamentally, all engagements for commercial shows are contract based. Australian theatrical history is a collection of one-time engagements with the most continuity had by production teams. If you accept that there is a systemic lack of diversity in Australian arts, then it is the product of a consistent and collective set of decisions with one of the few points of consistency being production.

Shows live within a particular context with specific implications for taste, and wider interpretation. It behooves one morally and financially to be aware of what is allowable in the global context of social appetite. What will audiences go for? How do these considerations affect programming, the composition of your creative team, and casting?

Image: Teamwork. OpenClipart-Vectors via Pixabay

ACCENTS

‘In Australia it appeared acceptable for Teddy Tahu Rhodes to portray a Frenchman in South Pacific but not the King in the King and I. Is that because one is white and just putting on a French accent and the other is Thai and should not be portrayed by a white man with a good tan?

Should the cast of Billy Elliot only be cast with genuine Geordies? Or when it comes to doing accents is it acceptable that a white actor can do the accent of a white race only but never anybody of colour?

Should an Australian be allowed to use an American accent to get the role of an American if there is a genuine American accented actor available?’

Accents are trainable elements and part of the actor’s craft. They can be put on and taken off just like pieces of costuming or spray tan. Is membership of a marginalised community group something you can put on and take off like an accent? Is it just another trick to ‘act more trans and non-binary’? Many trans and non-binary advocates would find the comparison naive to the extent of being negligent. I don’t however, I’m going to take Mr. Donnell at his word that these are genuine questions.

Are accents allowable in professional theatre? Absolutely. Is it considered better to cast actors who have as close to an authentic experience to the show requirement when casting for a diversity germane show? I think today, yes. Anecdotally, I’ve witnessed an emerging trend for both theatre and screen moving towards the redundancy of having accents as a skill, where actors are being sought specifically for their natural accents. Mileage may vary, and philosophically that doesn’t really impact the much larger issue which is the idea of authentic casting. But what happens when you can’t fin

d the exact right folk for the job?

Then, you must consider the difficult question of if inauthentic representation of a marginalised diverse community in your show will be viewed by enough of the wider society as harmful. This includes the decision making for accents. No one-size-fits-all approach will work. Personally I think that this social context urges creatives to consider authentic representation above all, and so professional use of accents and casting should be as close as possible to authentic.

I think that this doesn’t apply for the representation of non-marginalised, generally white cis communities, because the arguments towards lack of representation for those groups don’t apply. This is open to contest.

Image: Freedom of Speech. OpenClipart-Vectors via Pixabay

REDUCTIO AD ABSURDUM

Who gets to decide what should be respected and what shouldn't? Should a boy wizard only be played by somebody who identifies as a wizard?

Who gets to decide what should be respected and what shouldn't? Should a boy wizard only be played by somebody who identifies as a wizard?

Is the lived exclusion and background of being a trans and non-binary person, equivalent to the fictitious history of a Wizard?

In debating, there is a tactic known as Reductio ad absurdum, whereby you take an opposing view, and you extend it, showing that it will inevitably lead to a ridiculous or absurd conclusion. It’s a way of contesting the validity of opposing viewpoints and is generally considered poor form, because it displays a lack of understanding of nuance.

The nuance that you’re missing, Mr. Donnell, is any credence to the idea that there is harm in inauthentic casting. This is the central argument presented to you in the open letter produced by the Queer Artists Association, a letter that you were responding to.

Many of the points raised by myself have been made available to you previously. If your interest, Mr. Donnell were truly to have a debate to learn about and explore these ideas, would it not have done you credit to speak with a wide range of advocates for trans and non-binary and diverse equality in Australia BEFORE publicly posting your questions? If you had done this, you may have been able to present a more informed piece of writing than the one you have.

A Clown. Image: OpenClipart-Vectors via Pixabay

TALENT TALENT TALENT

The claim by Mr Hawkins and his team here is that Mr Sheridan was simply the best for the job, that everybody was seen including members of the trans and non-binary community, and that Mr Sheridan was simply better suited.

The claim by Mr Hawkins and his team here is that Mr Sheridan was simply the best for the job, that everybody was seen including members of the trans and non-binary community, and that Mr Sheridan was simply better suited.

The implication here is that if there were a trans and non-binary actor who simply had more skill and suitability to this production, that that trans and non-binary person *would* have been cast, or taken another way, that lack of trans and non-binary representation in this case is due to a lack of suitability and/or talent.

This is a very valid presentation of events, the difficulty being that it’s almost impossible to verify because privacy around the casting process is considered, quite rightly, as sacrosanct.

Can systemic bigotry hide behind the idea that ‘the best person was simply chosen for the job?’ Clearly the possibility exists.

Australia has a well-documented lack of diversity in the arts, particularly for the casting of diverse performers in professional engagements when diversity is not germane to the plot. It hardly happens.

‘Australia’s Creative Industry is shockingly white, but don’t be discouraged’ by Beverley Wang

‘No diversity: Australian musical theatre award accused of overlooking non-white artists’ by Stephanie Convery

‘Australia’s art institutions don’t reflect our diversity: it’s time to change that’ by James Arvanitakis

‘Why are Australian musicals so white?’ by Catherine Lambert

‘Most trans and non-binary Australians are silenced in the press: report’ by Jesse Jones

While some of the examples above speak specifically towards racial diversity, all lack of diversity affects all marginalised communities. Many of the arguments are philosophically the same.

The justification that the best person was chosen for the job, and that there is no systemic exclusion, fits for the micro: individual performers not meeting ‘the mark’, single shows, single talent competitions. This idea falls apart when you consider the macro, that this argument has led to lack of diversity over 5, 10, 15, 20 years.

Yet, it must be pointed out that there is merit to the idea that diverse performers are not talented or numerous enough. I think it’s important to talk about this.

Acting is a fickle industry. Actors as a demographic (like all professions) get better with more opportunities to work. If there are significantly fewer opportunities to work for certain community groups, it stands to reason that the overall capacity of that specific talent pool is going to be less developed in relation to other community groups.

A cycle.

The difficulty with this is that the evaluation of acting skill is never just objective. Yes, there are things you must be able to do, notes you have to hit, dance numbers that must be danced, and these are undoubtedly elements of skill.

However, the criticism is that the historic and widespread lack of non-germane-to-the-plot casting in Australia has less to do with ability, and more simply to do with preference. That producers are looking to reflect the preferences of a specific paying public, and how can you measure the line between preference and skill objectively?

I view acting skill as existing within a nuanced hierarchy. That the ability to hold a stage as a principal character in a show is fundamentally different, and more exacting, than the role of an ensemble member. The responsibility for storytelling is larger, and it takes a refined appreciation of craft that is undoubtedly slow to develop. I believe that there can be significant disparities in skill between individuals, wide gaps of experience, and so I give the idea that marginalised performers are on the whole less suited than their centralised peers, particularly in a small market like Australia, credence.

I also clearly see a lack of developmental opportunities for diverse creatives, which if left unaddressed, will continue the cycle. If there are fewer diverse performers entering our top training schools, and commercial casts, then it stands to reason that there will be fewer high level and battle-tested diverse performers, and creatives, and producers and stage managers, and designers.

But is that Mr Donnell’s responsibility? Is it the responsibility of training institutions? What next?

WHAT NEXT?

Teamwork. Image: GraphicMama-team via Pixabay.

This is the part where I bow out of the conversation. It is not up to me, as a non-member of the trans and non-binary community to make specific proposals on their behalf. I also do not represent the actors union in Australia, Equity, who are ready and waiting to enter these complicated discussions with heart and consideration. What I will do instead is collate some of the suggestions which have already been made by diversity advocates before me, in handling similar issues.

- Prioritise the casting of actors with authentic lived experience in roles which are fundamentally tied to a specific cultural identity.

- Engage cultural consultants for shows which are fundamentally about a particular diversity group.

- Take a census of the artists you invite to audition so that you can adjust your engagement with underrepresented communities.

- Have quotas of audition slots earmarked specifically for actors from diverse backgrounds.

- Specifically seek out and invite members of underrepresented communities to your auditions.

- Run mentoring and training programs with higher level practitioners specifically to upskill under-represented performers.

- Hire an officer whose responsibilities include social outreach towards, and the nurturing of underrepresented talent.

- Consult with advocacy groups such as Equity Australia and the Queer Artists Association when concerns are raised.

- Seek out and hire more creatives and executives from under-represented backgrounds.

Now that we’ve done all that, it should be easier to answer the questions that Mr Donnell poses at the end of his open letter.

MR. DONNELL’S CONVERSATION STARTERS

Where does the responsibility rest to attract and develop the number of BIPOC performers in our industry? Government funded education programs - NIDA, WAAPA, VAC? Subsidized Companies like MTC, STC, QTC, STCSA? Commercial Producers? Everybody?

Where does the responsibility rest to attract and develop the number of BIPOC performers in our industry? Government funded education programs - NIDA, WAAPA, VAC? Subsidized Companies like MTC, STC, QTC, STCSA? Commercial Producers? Everybody?

Yes.

Should quotas be considered across all of them? Yes.

How do we avoid tokenism? By treating opportunities extended to marginalised performers with dignity. By putting into place plans to mentor and train creatives who show promise. By holding these creatives to the same rigorous standards which stand at the highest levels of professional performance, but putting into place scaffolded support if they are less experienced.

Do we have a systemic racism issue in our productions, our writing, our casting, our teaching - and with our audience? Yes.

How do you successfully address or create awareness of systemic racism? A big question. Talking. Measures as I’ve suggested above are a start. By listening to the suggestions of stakeholders.

How can we be more immediately inclusive at a time when there are so few productions and theatres open? Just because there are fewer opportunities going, does that remove a moral responsibility to be against bigotry? Can I be a little bit bigoted because everything’s shut? Does the harm caused by poor or lack of representation change if there are fewer shows open? Many of the measures suggested in this article, and by other diversity advocates require very little financial investment, since they mainly fall under the purview of operations and strategy.

Who are the appointed and approved change monitors and observers? We all are. You should be. Advocacy groups exist to provide leadership around this, you have a plethora of options when seeking a measured response. I suggest you contact Equity Australia and QAAA as a start. Ideally, it’s a responsibility shared between all gatekeepers, training institutions, agents, casting directors, actors themselves, and above all, producers.

Finally - should the arts be the voice of change? Yes.

Do people care what our industry has to say or do they just want a 'nice nights entertainment'?

This is harder to answer, and will require you to do a little more research. It is valid to think that the concerns raised are less relevant if a statistically small percentage of the population reflect them. There are a great many articles, and a large social outcry right now. How do you measure proportional audience appetite? How do you measure the depth to which a particular attitude has penetrated within a demographic? Is this not the very central question to your entire profession Mr Donnell?

Should we be (or hold) the mirror the world needs to look into even if that damages support for our industry?

I have no idea what you mean by this, and think that your question is poorly worded.

Image: A Detective. GraphicMama-Team via Pixabay

CONCLUSION

The questions raised by Mr Craig Donnell are valid. They’re widely held in the hearts of many. I leave you with two thoughts.

Is diversity a burden to be dealt with, or can it make the work better?

Is the arts simply a transactional industry where businesses exchange talent and a ‘nice night out’ in exchange for money, or do the arts have a more human purpose of asking societally relevant questions, allowing audiences to question and explore elements of their own humanity? Do arts producers like Mr Donnell have a moral responsibility to uphold, and how do we determine how they are doing?

Over to you!

Chris Fung is an Australian performer based in the UK. His last two engagements (Cyrano de Bergerac at the Playhouse/ NT Live, and Evita at Regents Park) combined for a total of 7 Olivier Award nominations in 2020, as a writer he was previously written on diversity for AussieTheatre.com and TheatrePeople.com Photo: Robert Boulton

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.