Because the Night

Because the Night takes the story of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, removes all Shakespeare’s language, tweaks the story here and there, reduces the cast to six, changes a gender, relocates it to a 1980s timber town called ‘Elsinore’ where the timber workers and the very forest itself resist the old regime, and, boldest step of all, locates the production in an enclosed thirty-three room set through which the audience wanders at will, witnessing (but sometimes missing) the key confrontations of the drama.

Malthouse Theatre bursts out of COVID lockdown with this theatre event, which they claim with some justice is ‘Australia’s first fully realised immersive play’. And they have gone all out, throwing all their resources at it, taking over the Beckett and Merlyn theatres, dressing rooms, storage areas, and even the staff car park and making of all these spaces the key rooms of a royal regime in decline: a surveillance centre, throne room, a royal bedroom, a gymnasium, a child’s bedroom, a playground, a bunker, workers’ bars and carnival spaces, a sawmill… and so on. All linked by dim-lit lime-green and red plush corridors.

Director Matthew Lutton has recruited two talented and distinctly contrasting casts who alternate between shows: Hamlet (Khisraw Jones Shukoor or Keegan Joyce), Claudia (Nicole Nabout or Maria Theodorakis), Gertrude (Belinda McClory or Jennifer Vuletic), Ophelia (Tahlee Fereday or Artemis Ioannides), Polonius (Rodney Afif or Syd Brisbane) and Laertes (Ras Samuel Weldaabzgi or Harvey Zielinski).

Meanwhile, the audience is restricted to sixty each performance, and divided into groups of twenty, each group necessarily entering the space via a different door. Once inside, audience members are asked (ordered?) to don long black cloaks and black masks that suggest either a rabbit or a devil. (The masks are disinfected, and the cloaks dry cleaned after every performance.) Masks and cloaks may be irksome (and possibly make us look like extras in Eyes Wide Shut), but as audience members can almost always see other audience members, they successfully make us into spirits or ghosts, and enhance the atmosphere of incipient evil and dread. They also distinguish the audience from the contemporary dress actors (who totally ignore their audience) and the ushers, who wear white masks.

Once we enter the complex proper, the idea is to ‘follow’ one character or another so as to construct their story – or ‘choose your own adventure’. My particular entrance took me into what is then my Scene 1, in what appears to be a surveillance centre – a wall is lined with surveillance tapes, and screens reveal other rooms and characters. An agitated but trying-to-be-decisive Claudia (Maria Theodorakis on my night) confronts a paranoid Polonius (Rodney Afif), and we learn that Claudia is the new ruler of ‘Elsinore’ (and if we know Shakespeare’s play, we assume she has murdered Hamlet senior and usurped the throne.) Polonius warns that the ‘crosscutters’ are restless and making demands. She shocks him by wondering if those demands should be considered. Then both characters go their separate ways. Who to follow?

I take off down a corridor, but I am immediately distracted by the numerous highly imaginative rooms that open off it, designed by Dale Ferguson and ‘decorated’ (a most inadequate word in this case) I assume by Marg Horwell and Matilda Woodroofe. I’m further distracted by the overwhelming attention to detail and by wondering if Ms Horwell and Ms Woodroofe collected all this stuff themselves – such as the two rooms lined with myriad pigs of all sizes. The amount of work and thought is quite astonishing.

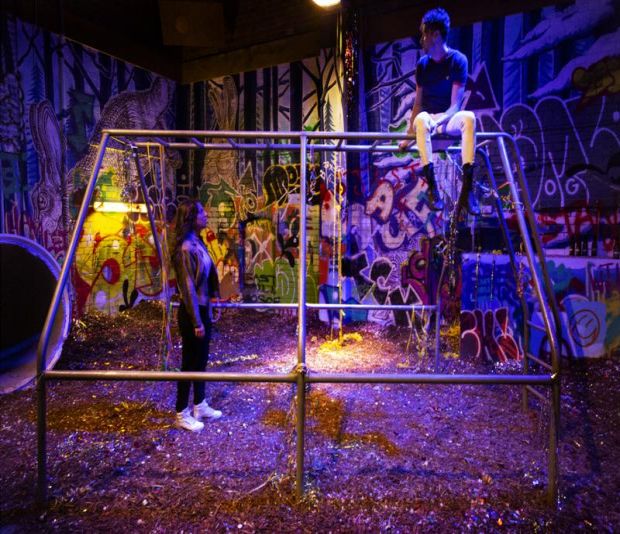

As it turns out, the cast will never enter many of these rooms, but they are in themselves allusive, suggestive, and tangentially support the mood or ambiance of the story. A room packed with toys somehow suggests Hamlet’s or Laertes’ childhood – two men reluctant to grow up? Play equipment on a floor of sawdust and woodchips. Push through some coats and furs and you are in a snow cave. A neon sign beckons into a nightclub. Other rooms suggest the time warped recreations and hangouts of the timber workers, with beer bottles and vending machines. But those ‘crosscutters’, ostensibly a threat to this fragile regime, are not represented by any character, their presence entirely a matter of exposition and ‘noises off’. A set-up without a pay-off.

If you are trying to construct or follow the story, you naturally attempt to integrate these rooms into it. Is this room important to the story – or, more precisely, the plot? As it turns out, no. They are, as it were, atmospherics, spooky and sad in being empty – or abandoned - but packed with things that meant something once.

I arrive at the royal bedchamber, still littered with funereal floral tributes, and find Gertrude/Belinda McClory, and I choose to follow her, perhaps because Ms McClory is so wonderful and has so much presence and authority. But this is a bad choice because, with all due respect to Ms McClory, Gertrude spends a lot of time alone, grieving or thinking, and then she’ll suddenly take off at speed – to go to another room - perhaps to cajole Claudia, who is Gertrude’s lover – but the corridor is choked with more cloaked and masked spectators who are following some other character – and Gertrude disappears.

Sometime later, and by chance, I find her in a gymnasium, berating angry Hamlet and warning him against Ophelia – whom I have yet to see at this point, but, in this iteration, of course, no maddened shrinking violet…

Across the ninety-minute running time, it is almost impossible to get or understand the whole story. Comparing notes with The Companion afterwards (we had gone our separate ways), we both realised that each of had missed different key scenes – so that in the final scene – the only one in which all cast, except Polonius, is on stage together – bits of the jigsaw are missing, and it does feel, after so much intrigue and set-up, somewhat anticlimactic and uninvolving.

Malthouse would like you to come again to fill in the gaps. It seems people are sufficiently intrigued to do so, but some familiarity with the Shakespeare original will help.

Perhaps the most interesting and contemporary aspect of Because the Night is the ecological strand, that of the resurgent forest. The trees, exploited as the source of this ‘royal’ family’s wealth and power, have had enough. Indeed, there are signs in a number of the rooms warning that the trees are already dangerous. And yet, this strand of the show feels like a gesture, an added layer of jeopardy (like the ‘crosscutters’), provided only by more exposition, lighting and ominous sound (J David Franske) and comes into full power only in the final moments.

Here then is a show that is adventurous and imaginative, but one in which the concept takes priority over what is, actually, a simple story, and over character and emotion. I remained curious throughout but had no emotional connection. I have been making up stories for forty years – and getting paid for it. I’d rather not do that in the theatre. I want the theatre-makers to tell me a story, to take me into another world and yet here another world has been made for me in excessive bewildering detail. For Because the Night to be truly immersive, it needs less distractions, more focus, more poetry, and wit, and more pay-off for what is set-up. Nevertheless, the concept and its originality will provide beguiling experiences for many.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Pia Johnson

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.