Blood on the Wattle

Playwrights often have a lot to say. Sometimes they try to say it all at once. Sometimes that can be a little confusing, a little overwhelming, even a little disturbing. Such is the case with Blood on the Wattle. It touches on tawdry party politics, climate change, refugee detention, racism, discrimination, misogyny, stalking … even rape. Significant themes. And theatre is a good way to air them. But packaging them into one play means a fair bit of manipulation. And a fair bit for the audience to navigate.

In Blood on the Wattle, Geoffrey Sykes creates Karl Matters (Ken Welsh), a federal politician representing a country electorate for the fictitious, conservative “Country First “ party. Karl has ‘fallen out of favour’ with his conservative party leadership because of his views on climate change. He may even lose preselection. His secretary and stalwart supporter, Louise (Kloud Milas), is determined to stand by him. A play in itself, perhaps?

But it becomes more complicated.

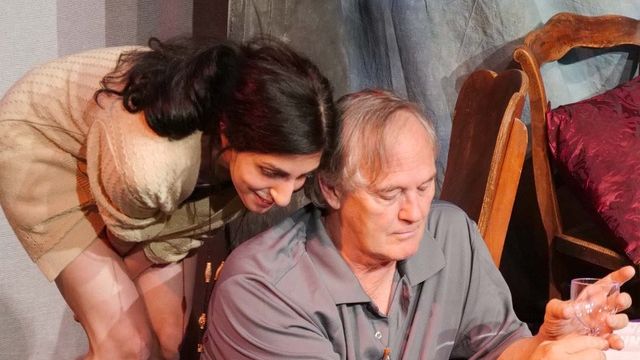

Karl meets Vania Azadi (Befrin Axtjärn Jackson), a newcomer to town, who has found employment at a local farm. When Karl offers her work in his office, Louise’s prejudices are revealed. As Karl becomes more obsessed with Vania, his persistent personal questions about her past lead to a theatrical treatise on government immigration policies and disturbing disclosures that might require prior warning for audiences. Vania’s story itself could be a second play.

Most of the action occurs in Karl’s office on one side of the stage, and Vania’s small flat on the other. Many of the scenes are short, and Sykes feels the need to identify the quick changes via slides on a screen, which prove a relatively unnecessary distraction (and an annoying light source) due to the clearly differentiated staging and his actors.

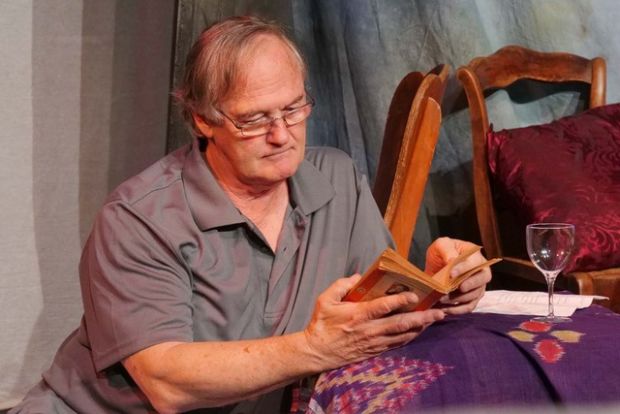

Welsh is realistically ‘political’ as friendly, sociable local member Karl. His voice resonates in brusque political phone calls, but carefully changes tenor as his confidence and bravado slowly erode. Welsh shows that gradual erosion perceptively, especially in some of the longer scenes in the second act.

Axtjärn Jackson is a thinking performer who brings believable sensitivity to her interpretation of Vania’s story. Though it is often very hard to hear her in the first act, she finds more vocal intensity in Vania’s angry reactions to refugee policies and her acute pain in the retelling of her treatment in detention. Some of these scenes demand intense control of emotion – and real guts to enact.

Milas is consistently supportive as Karl’s electoral and business office manager, despite some repetitive dialogue which is always hard to vary.

Sykes has the making of a good play here – or two good plays. There are some pertinent messages, and some moving, heart-breaking moments. The fact that they are told in so many short scenes that move so quickly diminishes their intensity. Fortunately, it is the anguish of some of the later scenes that remain with the audience.

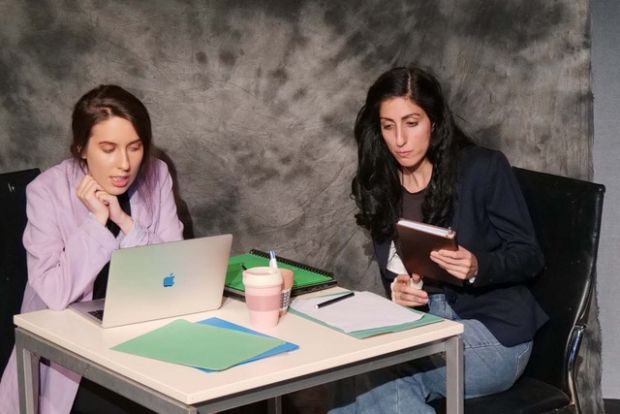

Plays that encompass so many themes and backstories can become confusing without serious workshopping – and it’s very hard for playwrights to workshop and critique their own work. Or to direct it effectively without engaging the assistance of a dramaturg. This is where dramaturgs come into their own. In a complex play such as this, a dramaturg’s experience, distance from ‘ownership’ and impartial advice would have been of great benefit.

Carol Wimmer

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.