A Clockwork Orange

I’ve been struggling to find the words to review something, which is so visually simple, and yet so utterly compelling. When Anthony Burgess wrote his novella A Clockwork Orange over 50 years ago he had no idea the impact and cult following his tiny text would have. It wasn’t just that the language was so interesting – a joining of Russian and English slang into “nasdat” - but more its central themes of free will and what it means to be young which have resonated for half a century. When Kubrick adapted the text for film in 1971, the 1962 novella became one of the most important texts of the 20th Century. This importance, however, came in the fear of glamourized “ultraviolence” and tended to forget the core messages of Burgess’ work - what happens when you take away free will? What does it mean to be an adolescent? What is power? It also spawned countless stage adaptations based on the film.

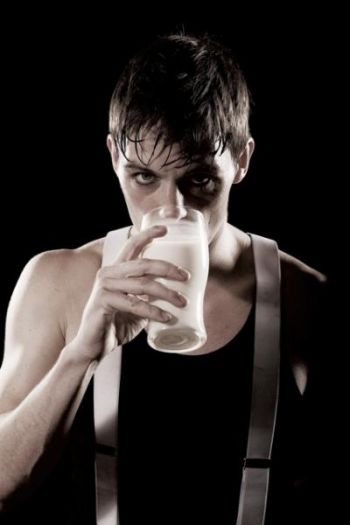

So what do you do when your text is getting lost in the translation? Write the definitive playscript. And that’s exactly what Burgess did. Director Alexandra Spencer-Jones and her Action to The Word theatre company have staged an all male adaptation of Burgess play and it is immaculate. With the use of four chairs, a table, a hospital bed and four glasses of milk she has managed to transport the audience into the streets, “milk-bars”, schools, prisons and homes of a futuristic dystopian London. This is achieved in large part by the utterly mesmerizing performance of Martin McCreadie as the lead droog Alex DeLarge. McCreadie has a foreboding physical presence and yet seemingly effortlessly switches between the naughty schoolboy aspects of Alex and the insanely violent and nihilistic leader of his droogs. Played out in 90 minutes with no intermission, McCreadie owns every piece of the stage, which is a good thing because he never leaves it. Whether it be prowling with menace in his eyes or cowering and convulsing in pain after the aversion therapy known as the Ludovico technique, it’s hard to keep your eyes off this extraordinary young actor.

So what do you do when your text is getting lost in the translation? Write the definitive playscript. And that’s exactly what Burgess did. Director Alexandra Spencer-Jones and her Action to The Word theatre company have staged an all male adaptation of Burgess play and it is immaculate. With the use of four chairs, a table, a hospital bed and four glasses of milk she has managed to transport the audience into the streets, “milk-bars”, schools, prisons and homes of a futuristic dystopian London. This is achieved in large part by the utterly mesmerizing performance of Martin McCreadie as the lead droog Alex DeLarge. McCreadie has a foreboding physical presence and yet seemingly effortlessly switches between the naughty schoolboy aspects of Alex and the insanely violent and nihilistic leader of his droogs. Played out in 90 minutes with no intermission, McCreadie owns every piece of the stage, which is a good thing because he never leaves it. Whether it be prowling with menace in his eyes or cowering and convulsing in pain after the aversion therapy known as the Ludovico technique, it’s hard to keep your eyes off this extraordinary young actor.

McCreadie is backed by a wonderful ensemble of male actors. Neil Chinneck effortlessly switches between the snide and overly confident Dr Brodsky into the troubled F Alexander and even takes a turn at playing one of only two female characters in the play, Alex’s mum. Chinneck embodies each of these characters so well that you actually forget that it’s the same actor. The ensemble is solid and focused but in the end this is McCreadie’s show.

Spencer-Jones blends modern industrial, pop and classical music to provide transitions and evens some stellar dance numbers. Hannah Lee’s choreography of the Billy Boy sequence introduces the audience to the violence of the world we inhabit with an unnerving amount of grace The audience is transfixed by Alex’s treatment sequence, as the Scissor Sisters belt out Comfortably Numb and Jefferson Airplane sing the ethereal White Rabbit. The actors become the set as Alex climbs the ladder in his hallucinations.

There has been much made about the homoerotic nature of this production and so it rates a mention here. Whilst Spencer-Jones claims that the production stays true to the text, except some girls are boys, this may be a little naïve. One of the themes of the original text revolves around power and the young Alex DeLarge exerts his power over women in sexually violent ways. Changing those young women to young men may well change that theme to something wholly more testosterone driven and to some less horrific. That said, this play is riddled with sexuality and sexual violence and does not try to shy away from the horrific sexual proclivities of its antagonist. Similarly there are always some problems with the depiction of this text, given that Alex is only 15 at the beginning and 19 by the end and of course McCreadie is clearly in his 20s.

In the end, however, McCreadie holds the audience in the palm of his hand as Alex, matured, looking for love and having grown out of his ultra-violent ways. It’s a thing of mesmerizing beauty, which leaves the audience with as many questions as answers. Spectacular.

L.B. Bermingham

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.