Corporel

A lot of performances are called ‘unforgettable’ by us hyperbole-prone reviewer types, yet few truly are written in indelible ink on one’s hippocampus. There’s not even a smidgeon of hyperbole in the following statement: I will never forget Corporel.

Presented by Brisbane Music Festival and performed by the brilliant Alex Raineri, this was a night where music and its definition was stretched, provoked, and reconsidered. Raineri is best known for coaxing beauty, clarity, and spine-tingling finesse from a grand piano. Working adjacent to his comfort-zone, Corporel featured compositions that saw him make music out of matches, radios, the human body, onomatopoeia, water, and even lunch. In doing so, he demonstrated a performer’s version of conceptual free-climbing: fearless, playful, and technically formidable.

The evening opened with Yoko Ono’s Lighting Piece. In the darkness of FourthWall Arts, Raineri struck the match, and the room contracted around the tiny flame. Instantly we became hyper-aware of how much sound hides in stillness. The scrape of a shifting chair, the hum of traffic beyond the wall, even our own breath became part of the composition. It set the tone for an evening of avant-garde exploration.

Jennifer Walshe’s becher received its Australian premiere, and Raineri tackled it with a giddy kind of precision reserved for musicians who find delight in the nearly impossible. The work ricocheted between musical references—pop, classical, everything in between—like skipping from one radio station to another in quick succession. Each fragment snapped into a new tempo or time signature before the last could settle. Raineri’s ability to thread coherence through the chaos was remarkable. His internal pulse, whatever clock he keeps in his bones, should be studied.

The show then swung into Chappell Roan territory with a gloriously camp piano arrangement (by James Dobinson) of Pink Pony Club. The brief, we were told, was to lean into flamboyant maximalism. Dobinson delivered and Raineri doubled down. The result was a dramatic homage that pirouetted through stylistic nods to Chopin, Mozart, Strauss, and even ragtime. It was decadent, joyfully over the top, and a firm favourite with the audience.

Cowell’s The Banshee, written entirely in extended techniques, was executed on what Raineri jokingly referred to as his “stunt piano.” With a dumbbell on the sustain pedal and hands plunged into the instrument’s interior, he summoned winds, sighs, groans, distant storms and spectral voices. Cowell’s score requires a kind of sonic spelunking, and Raineri inhabited the uncanny world with relish and control.

John Cage’s Water Music brought the comic absurdity, requiring the performer to keep a straight face while wrangling a radio, water bowl, duck call, a deck of cards, and a piano. It was a genuinely hilarious example of Cage at his most impishly theatrical. The score displayed on screen added to the delight; watching its cryptic instructions unfold only amplified the sense of joyous craziness.

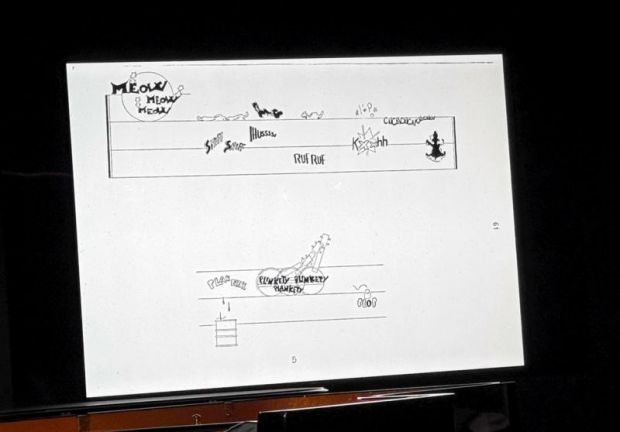

Cathy Berberian’s Stripsody was another graphic playground we could enjoy on screen. The score unfolded like a comic book cracking to life. Pops, bangs, whooshes, squeaks; the music consisted of an A-Z of onomatopoeia. Raineri fearlessly unleashed a flurry of vocal acrobatics as we watched the score on screen, matching it with the creative leaps he was making in real time.

Vinko Globokar’s ?Corporel marked one of the night’s most intimate moments. Shirtless, barefoot, cross-legged on the floor, Raineri used his own body as a resonance chamber. In this daring percussive work, his slaps, taps, clicks, consonants, breaths and claps created the beat. The artist’s literal pain was unflinching and the work’s vulnerability was unmistakable. At times it felt ritualistic, at others unsettling, but it was always compelling due to Raineri’s commitment to the work’s physical and emotional intensity.

The program closed with Ono’s Tunafish Sandwich Piece, performed with a mix of sincerity and cosmic whimsy. Sitting at a small table, now simply a man making a sandwich, Raineri returned us to the hyper-attentiveness of the opening work. The quiet chewing, the clink of cutlery, a cough, a shifting audience member, and the murmur of a passing car, all became part of the score. The piece’s collision of existential imagination and everyday nourishment landed beautifully: a meditation disguised as lunch.

Throughout the night, Raineri’s performance was a masterclass in versatility, discipline, and interpretive daring. Few artists could navigate such a kaleidoscopic performance. BMF deserves recognition for assembling a program that challenged and delighted, offering Brisbane a rare evening of unconventional entertainment.

Corporel was not an easily accessible, basic concert to please everyone and nor was it meant to be. It was an exhilarating reminder that music doesn’t just come from instruments. Sometimes it comes from matches, from bodies, from chaos, from courage, and sometimes, it comes from the perfect bite of a sandwich. After all, you can tune a piano, but you can’t tune a fish.

Kitty Goodall

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.