The Dictionary of Lost Words

Set against the slow, meticulous, and selective creation of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), The Dictionary of Lost Words traces the story of Esme Nicoll (Brenna Harding) – a fictitious character - from a precocious child of four in 1886 to a thirty-three-year-old mature woman in 1915 – plus an epilogue set in 1889. The play is the story of Esme’s education – literary and moral - change and growth from a cossetted, insulated, timid, curious girl to a complex and courageous young woman who becomes a lexicographer, but finds experience in the wider world, is challenged and inspired through the Suffragette years, who chooses a loveless but sensual sexual initiation, suffers the loss of a child, but finds real love at last. It is in watching Esme, a kind of exemplar of that time of the changing place and status of women, that engages us through this rather over long play.

Esme always wanted to be a lexicographer like her widower father Harry (Brett Archer); he is just one of the lexicographers employed by Sir James Murray (Chris Pitman) Senior Editor of the OED. Countless words are sent in by ‘volunteers’, each word accompanied by a quotation, dated, showing the word’s use. The lexicographers are nicely individualised – cold, rude Mr Crane (Carlos Sanson Jr), Esperanto speaker Mr Maling (Anthony Yangoyan) and the solemn Mr Sweatman (Angela Mahlatjie) - all men. Esme must prove herself and earn Murray’s trust…

The question explored is whether words mean different things to men and to women. Who uses which words and what do they mean by them? And so the making of Esme’s own dictionary of ‘lost’ words emerges. They are words collected over most of her life – via questioning, via her alert awareness. She doesn’t quite know what she will do with these words beyond keeping them secret in her maid, Lizzie’s (Rachel Burke) trunk, but she is compelled to collect them – and always carries pencil and paper ‘slips’ – just like those the volunteers send in and the lexicographers use in compiling the OED.

Esme’s lost words – from Lizzie, from old ex-prostitute Mabel (Ksenja Logos) at the Covered Market, from racy actress Tilda (Angela Mahlatjie) and her louche brother Bill (Anthony Yangoyan) - are not in the OED and won’t be. Such words are rejected as ‘unsuitable’, ‘surplus’, unvindicated by any written, printed quotation. They are merely spoken - mainly by women – or are slang, colloquialisms, the language of the street and of the working class – but in common, everyday use. (I’d have liked more examples than we get.)

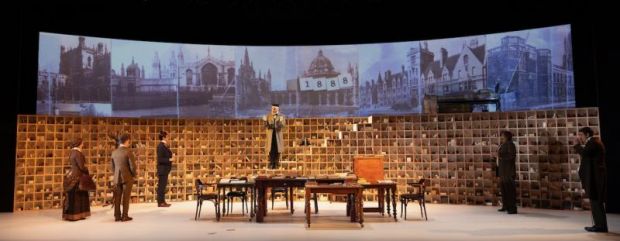

Multiple locations and character development are conveyed by some brilliant collaborations of set designer, costume designer and director. Jonathan Oxlade’s set design is suggestive, utilitarian and inspired. His double height bank of seven hundred pigeonholes, fronted by desks covered with books and papers immediately tells us we are in the ‘Scriptorium’ where the work on the dictionary takes place, but those pigeonholes can also be lit from within to suggest other times and places, and contain spaces for sitting room cups and saucers and a teapot, and conceal doorways and a flight of stairs. The stairs go up to a second level where we find Lizzie’s room – and her trunk – and a cyclorama on which are projected signs, streetscapes, embroidery, handwritten notes and the horrible cost of WWI. Ailsa Paterson’s costumes not only suggest the passage of time, but with five of the cast of eight doubling up, distinguish multiple characters. When Esme visits the Covered Market with Lizzie and meets Mabel, the stage is transformed in seconds via Jessica Arthur’s imaginative, efficient direction, more costume changes, economic choice of props, Trent Suidgeest’s lighting and Max Lyandvert’s subtle soundscape. For the moment, the pigeonholes seem to disappear.

In adapting Pip Williams’ much-loved, best-seller novel, Verity Laughton faced a daunting task. My paperback copy is 406 pages, and the story’s timespan is nearly thirty years. A sort-of rule about biographical drama is to restrict the telling by rigorous choice to one or at most a few key incidents in the subject’s life that might suggest the whole. Instead, Laughton bravely takes on the whole thing – her artistic choice made perhaps because Esme is mostly a reactive character, plus Laughton being well aware of the novel’s status and not wishing to disappoint its readers.

Certainly there are wisely chosen elisions and deletions, but in ‘covering’ so much there is an over-reliance on careful but wearying exposition and ‘explaining’ context – and also a certain flattening effect tending toward a ‘niceness’ that can be felt as anodyne. Esme’s decision to sleep with Bill – because she’s curious about desire and her body (as she explains later) – is glossed over rather quickly and is as unconvincing as it is in the novel. Despite illiterate Lizzie explaining to Esme why she is ‘knackered’ all the time, I wondered – in a story about words and liberation – why Esme never teaches Lizzie to read. Esme’s slow burn love interest Gareth (Carlos Sanson Jr) is a typesetter in the novel – and therefore there’s a class difference between them. But on stage, Gareth has a rather upper-class accent and looks a bit of a toff. In the novel, toothless Mabel is so filthy that Esme recoils from her stench. Ksenja Logos makes a fine transformation into the character (from the upper-class intellectual godmother Ditte), but it is rather sanitised and unconvincing.

In a play about words, one can’t help feeling that there are too many. By contrast, there is a sequence without words: it is when Esme is dutifully obliged to confess to Bill her sexual past and its aftermath. Instead of a long speech (which Laughton would’ve had to invent), Jessica Arthur stages a brisk, silent but absolutely clear summary in movement of Esme’s past. It is a magical and beautifully directed moment. Would that there were more like it here.

Readers of the novel – and clearly, they are legion – will be well-equipped to follow the story as each of the key incidents are dramatised or ‘covered’ – without, I think, feeling too much has been left out. Those who’ve not read the book may struggle just a little. As a play, The Dictionary of Lost Words is a mix of touching scenes, of comedy as Esme encounters the outside world, and wordy narration and at times rather preachy idealism. It is certainly an ambitious and admirable but somewhat mixed achievement.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Pia Johnson

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.