It’s Time

It’s Time, written and directed by Chamkaur Gill and presented through a collaboration between Panda Entertainment Networks and Robina Literary Club, is an intimate and confronting exploration of post-war trauma. Based on real conversations with Vietnam veterans, the play centres on a man attending his first psychiatric session. Throughout the production, the man attempts to unpack years of buried guilt, memory, and pain. Rather than simply recounting events, the production places the audience inside the psychological space of its protagonist, inviting us to sit with discomfort rather than observe from a safe emotional distance.

The story unfolds primarily within a psychiatric consultation between Tom Maarschalkerweerd (Carey Parsons), a Vietnam veteran attending his first evaluation for post-war trauma, and Dr Phillips (Craig Thompson), the calm but probing psychologist attempting to guide him through memories he has long suppressed. Sharing the stage is Tom’s inner voice, embodied by a Soldier (Rowan Hinton), who externalises the thoughts, fears and intrusive recollections Tom cannot yet say aloud. As the session progresses, the audience witnesses not only a conversation between patient and doctor, but a layered confrontation between a man and the parts of himself he has tried to bury.

Hinton opens the play alone on stage, delivering a monologue as the embodied conscience of the veteran. He paces, circles, stares directly at the audience, and reacts to the dialogue spoken between Tom and Dr Phillips. The concept is effective as his trauma is shown as something separate yet ever-present, lingering in the room and refusing to be ignored. Hinton speaks aloud the anxieties, intrusive memories, and unspoken thoughts that Tom cannot yet articulate. While he struggled at times to authentically connect to the more rage-driven sections, occasionally appearing disconnected from the anger he was attempting to portray, there were moments where he found powerful grounding. One particularly powerful monologue centred on grief and remorse was deeply affecting. Hilton let his eyes glisten with real tears and, in that vulnerability, he truly shone.

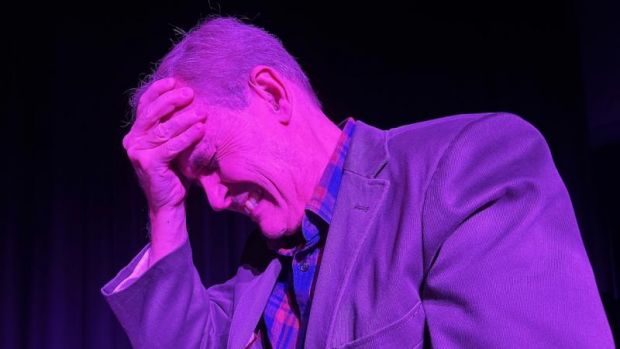

Carey Parsons carries the emotional weight of the production as Tom. His performance is physically detailed from the outset. Throughout the piece, Parsons is constantly flinching at sudden sounds and tightening his posture all while wearing pained expressions that show his wounds still feel very much alive. A visceral reaction to a ringing phone stands out as a moment where the trauma becomes unmistakably embodied. Initially reserved and controlled in his interactions with the psychologist, Parsons gradually allows the character to unravel. It is truly compelling to watch as the macho character of Tom slowly unwinds and release years of repression without even fully realising it. By the final reconciliation scene, the emotional dam has clearly broken, with genuine tears falling as a clear testament to the passion these performers had.

Craig Thompson was perfect as Dr Phillips. He presented the character with a wonderfully calm and measured presence. However, when Thompson first enters, he is visibly nervousness. With shaking hands and tapping feet, it was clear to see that he is not used to the pressure of the stage. And yet, this nervousness never disrupts his vocal delivery. If anything, the slight trepidation adds authenticity to the idea of meeting a new patient with complex needs. Thompson’s tone is steady and soothing throughout, projecting clearly and providing a stabilising counterpoint to Tom’s volatility.

In the second act, Doll Nguyễn Ashenden appears as the Vietnamese mother. Despite limited stage time, Ashenden leaves a strong impression. Her presence is quiet but powerful, and the final scene carries such heavy emotional weight that it was a struggle to take your eyes off her grieving expressions.

In the second act, recorded voiceovers performed by Thiện Đình Trần recite the poetic letters that Tom has kept since the war. During these moments, Hinton stands in the background, visually representing the deceased soldier. The recordings themselves, however, shift the tone significantly. The audio-visual effects throughout the second act unfortunately break some of the immersion built in the first half, and the production does not fully prepare the audience for this tonal change. What initially feels like an intimate therapy session becomes more stylised and distanced. While the recordings could be interpreted as a ghostly echo of the past, the choice ultimately lessens the immediacy of the moment.

Then the ending arrives quickly. Just as Tom seems most emotionally exposed, the session concludes with an abruptness that starkly mirrors the reality of therapy itself. You open up, reach a vulnerable place, and then time is up and you are left to sit with what has been unearthed.

The script itself is dense and at times overly verbose. There is extensive use of psychological terminology and military-specific language, including detailed references to trauma responses and the amygdala. While clearly written with a particular audience in mind, this level of vocabulary risks alienating viewers who may otherwise benefit from the subject matter. That said, the dialogue is often poetically descriptive and conversational in tone. Even when the cadence feels uneven, the exchanges between characters feel responsive and natural. The progression of Tom opening up unfolds emotionally in a way that feels rapid, even though the overall pacing of the play is slow.

The staging is simple but effective. The set resembles a standard psychologist’s office, complete with white shelving, fake plants, stacked folders and an ageing corded phone. The openness of the space is striking. Although it is meant to be a contained therapy room, it feels large and exposed. That spaciousness allows the themes to take up room instead. The theatre itself is intimate, with no strong divide between the audience and the playing area, which heightens the sense that we are witnesses inside the session rather than detached observers.

Costuming, sourced by the cast themselves, subtly supports the themes of the play. Tom’s muted clothing and army green jacket hint at his military past and practical nature, while Dr Phillips’ neat navy suit and patterned tie reinforce his professionalism and composure. The only distracting element was the Soldier’s dog tags, which appeared visibly homemade and pulled focus from an otherwise cohesive look.

Behind the scenes, this production clearly feels like a passion project for everyone involved. With a team bringing backgrounds in academia, medicine, literature, community theatre and lived cultural experience, the creative voices shaping the work come from places of personal connection rather than commercial ambition. That sincerity is evident throughout. The play feels driven by a genuine desire to honour veterans’ experiences and to spark empathy and conversation. Whatever its imperfections, the heart behind the project is unmistakable.

It’s Time is an important work that seeks to humanise Vietnam veterans and confront the long shadow cast by war. It tackles masculinity, mental health, faith, and reconciliation without shying away from discomfort. While uneven in pacing and occasionally heavy in language, the production clearly encourages empathy and reminds audiences that trauma does not end when the battlefield is left behind. It is a reflective and challenging evening of theatre that asks for patience and rewards it with moments of genuine emotional truth.

Review by Rebecca Lynne

Photo credits: Bee Chen Goh

Tickets: https://hota.com.au/whats-on/live/theatre/its-time

Robina Literary Club: https://www.instagram.com/robina.lit.club/

Panda Entertainment Networks: https://www.facebook.com/Pandanetwork

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.