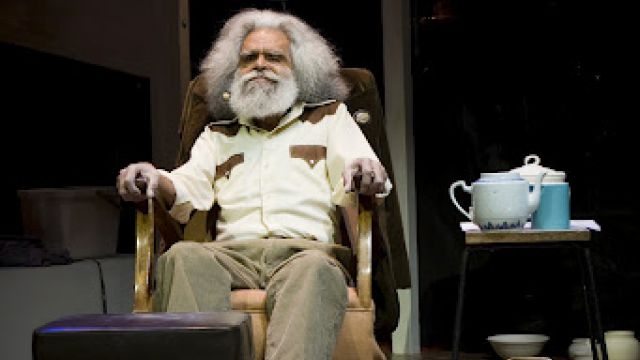

Jack Charles v The Crown

Advance publicity, billing Jack Charles as a recently reformed heroin addict and cat burglar, made me ponder what kind of tale he was going to spin; cautious lest, albeit subtly, it excuse, even glorify, social destructiveness.

Despite a frank introduction to the actor's former heroin habit, I needn't have been concerned. Strangely, the performance, though dealing much with them and offering subtle insights into their genesis, was not about Charles's former bad habits. Rather, it featured the life within which they occurred: a childhood of the Stolen Generation; a career littered with performance success; repetitive punitive action; and the merest hints at sustained systemic abuse and violence toward him.

Yet what Charles chose to focus his audience on was not even these sustained features of his life, but rather the freedom he had, even in harsh prison conditions, in his spirit.

What is this freedom that keeps a man so advanced in years and experience so obviously young in motion and attitude? Evidently, whatever it is, it keeps him creative and appreciative, and this is what shines through his work. Jack Charles is a veteran film, television, and stage performer, and his ability to hold us with a sprinkling of songs merely knocks up one more talent. But he can hardly be bettered in his ability to mesmerise with an overtly simple tale.

Charles's approach to his own story is fascinating in explicating the inexplicable: failure in success, success from failure, and, above all, the return to himself of a man who, having been stolen, was lost and now is found.

Charles's approach to his own story is fascinating in explicating the inexplicable: failure in success, success from failure, and, above all, the return to himself of a man who, having been stolen, was lost and now is found.

Charles's mixture of humility and pride might have evoked distaste had it subtly excused, even glorified, poor judgement; but his openhearted honesty, his ability to connect with others, and his preparedness to put himself aside in entertaining us very obviously evoked a great deal of fellow feeling even in those of us whose life paths have had nothing, or at least nothing obvious, in common with his. Supported by interesting but unobtrusive stage design, very effective lighting, and great audio, the performance succeeded in keeping audience focus where it was meant to: on a well-told story.

As if this journey weren't enjoyable enough, the act is accompanied by a trio of musicians whose performance was utterly virtuosic. Led by musical director – guitarist – violinist Nigel Maclean, with Phil Collings on drums and percussion and Mal Beveridge on electric bass, and with Gary Dryza's audio engineering evidently providing solid support, this trio rescues modern jazz from doo-wop and sends it mainstream, making it music you can hear as song and feel as dance. Come for the music alone, and you'll leave feeling that you've gotten your money's worth. The musical performance that allows me to speak of impeccable timing is a rarity to the point of near extinction. That alone delineates this trio from the majority. Its timing is not merely impeccable, but exquisite: as exquisite as its blend of vocal and instrumental harmonies and its sound design.

As if this journey weren't enjoyable enough, the act is accompanied by a trio of musicians whose performance was utterly virtuosic. Led by musical director – guitarist – violinist Nigel Maclean, with Phil Collings on drums and percussion and Mal Beveridge on electric bass, and with Gary Dryza's audio engineering evidently providing solid support, this trio rescues modern jazz from doo-wop and sends it mainstream, making it music you can hear as song and feel as dance. Come for the music alone, and you'll leave feeling that you've gotten your money's worth. The musical performance that allows me to speak of impeccable timing is a rarity to the point of near extinction. That alone delineates this trio from the majority. Its timing is not merely impeccable, but exquisite: as exquisite as its blend of vocal and instrumental harmonies and its sound design.

With such talent accompanying the show, it is perhaps unsurprising that Jack Charles and co-author John Romeril's creativity has fruited so sweetly in Charles's remarkable performance.

John P Harvey

Photographer: Bindi Cole

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.