The Lifespan of a Fact

A crackling three-hander comedy that goes much deeper than ‘funny’ – even while staying funny till its final moments. On a Friday afternoon, Emily Penrose (Nadine Garner), editor of an up-market New York literary magazine, assigns intern Jim Fingal (Karl Richmond) to fact-check an essay by esteemed writer, John D’Agata (Steve Mouzakis). It’s a straightforward assignment, maybe three or four facts, a make-work thing, really – and the magazine must go to the printers first thing Monday…

Within seconds, The Lifespan of a Fact establishes itself as a comedy. That is, we are given permission to laugh. You might think, with some apprehension, that the comedy will depend on the clash of no-nonsense grown-up realist Emily and tone-deaf intern Jim– an ambitious, desperate to please, literal-minded, nerdy Harvard graduate. But our interest – and a different kind of apprehension – deepen as we realise that Jim will go all the way out on an obsessive limb in defence of ‘fact’. The piece to be checked runs to 15 pages; Jim’s fact check runs to 130…

John D’Agata insists that his piece ‘What Happens There’, about a teenage suicide in Las Vegas, is an ‘essay’ not an ‘article’ – that is, not journalism. He insists that he has conveyed the theme, mood, ambiance, and deeper ‘truth’ of the story. He is adamant about the poetry and rhythm of his prose rather than strict, checkable accuracy.

But Jim insists that it’s a fact that some of John’s ‘facts’ are not ‘factual’: some bricks are in reality brown, not red, something happened ‘near’ a building, not ‘at’ it, and so on. As Jim point out to John, on social media, folks won’t care about the poetry; they will pounce on John as a liar.

As we watch and listen to the back-and-forth between John and Jim – and realist Emily’s attempts to umpire – we are torn between both sides of the argument. From what we hear of the ‘essay’, we can understand – and sympathise with – John’s intentions – even if he is just a little precious and arrogant. At the same time, we must acknowledge Jim’s sense of responsibility to the readers, who expect the facts to be sourced, verifiable and undeniable – even if Jim himself is maddeningly irritating and literal-minded. Some untruths that Jim seizes on maybe don’t really matter that much, but others really do – such as the manner of another suicide the day of the ostensible subject of ‘What Happens There’.

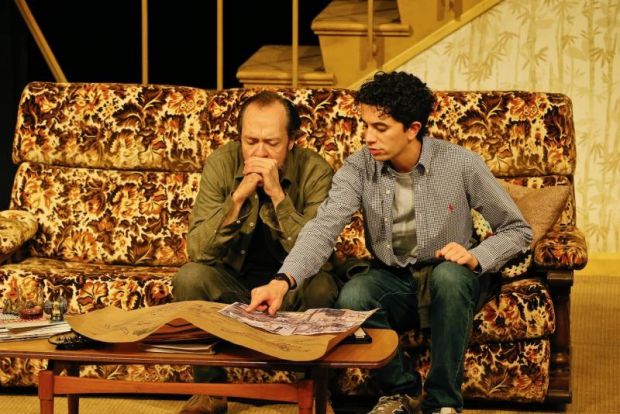

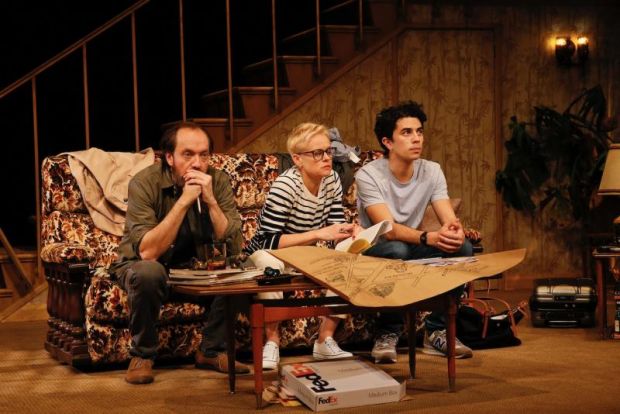

Andrew Bailey’s design makes a telling comment on the conflict. Emily’s office at the magazine in New York is all uncluttered glass and metal – a site of power and prestige. John D’Agata’s house – a superb reveal when we get to it – is a shabby, dated townhouse with ugly furniture. Paul Lim’s lighting emphasises the contrast, and Kat Cham’s costumes show us Emily’s New Yorker style, John’s daggy careless writer, and Jim’s millennial just-outa-college jeans-and-sneakers for all occasions.

‘Fact checking’ is a relatively new phenomenon, but in the current political environment of ‘fake news’, straight-out lying and casual bullshit, it has become central, crucial and topical. John D’Agata (the character and the real writer) is hardly the first writer not to let facts get in the way of a good story. The whole ‘New Journalism’ movement of the 1960s (Tom Wolfe, Hunter S Thompson, Norman Mailer, et al.) made non-fiction fiction an exciting phenomenon, but then did Herodotus tell the absolute truth about the Greco-Persian wars? Athenian Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War? Shakespeare’s propaganda for the Tudors? Didn’t Picasso say that the artist must lie to tell the truth? But what is truth?

It is these questions that give us the depth as well as the comedy, the clash of personalities as well as ideas, of The Lifespan of a Fact. Petra Kalive never lets debate dominate the comedy, nor the entrenched positions become static. She and the cast give us physical comedy entirely in keeping with the characters and text – which makes the evening all the more entertaining. Nadine Garner makes the most (as you would expect) of a largely functional role, but when she has had enough and exerts a commanding authority, we are thrown back in our seats. Steve Mouzakis gives us a John D’Agata initially simply, irritably astonished at being questioned and then – he’s by no means a bad man – supressing an understandable rage. As for Karl Richmond, whose debut with the MTC this is, his Jim Fingal is a wonderful, sustained performance. With perfect comic timing, he generates a fine and essential ambivalence in the audience.

Some may be disappointed in the lack of ‘resolution’ – but how could there be one? The ‘truth’ that John D’Agata went after is that some people died – and that is a fact. Why or how is open to interpretation.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Jeff Busby

PS: The assigned writers’ credits as per the program is misleading. Gordon Farrell worked on his adaptation adaptation alone. Mr Kareken and Mr Murrell began the project, collaborating with producer Norman Twain on their version and that is the version produced here by the MTC. So perhaps the writers credits should read: Gordon Farrell and Jeremy Kareken & David Murrell. This correction comes from Mr Kareken himself, so we can take it as a fact.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.