The Maids

‘Mistress is kind,’ says Claire, though her sister Solange isn’t so sure. The two siblings are maids under a powerful woman who keeps them in line with fear and faux friendliness. Whilst their mistress is out, the two maids play with her clothes and make-up, acting out extreme versions of their interactions – their sadomasochism building them both to a sexual frenzy.

Claire has written letters that have put a man in jail – the partner of their mistress – and as the two sisters act out the fantasy of strangling their employer, the thoughts that their part in the arrest may be discovered, elevate the make-believe to a real plot to murder.

French writer Jean Genet first presented The Maids to Parisian audiences in 1947, and they were shocked then by the blurring of fantasy and reality, love and hate, from the working classes to their masters and mistresses. When Andrew Upton and Benedict Andrews translated and updated Genet’s words to twenty-first century English, the same themes of class revolt and simmering sexuality lifted it above the profanity and pop-culture.

Director James Watson has taken this later translation and made it his own, as the opening play of his second year of residence at Goodwood. His 2023 productions were powerful, intimate portrayals of self-love and hate, and that body of work earned an Adelaide Critics Circle award for ‘Famous Last Words’, the production company run by Watson and Emelia Williams.

Director James Watson has taken this later translation and made it his own, as the opening play of his second year of residence at Goodwood. His 2023 productions were powerful, intimate portrayals of self-love and hate, and that body of work earned an Adelaide Critics Circle award for ‘Famous Last Words’, the production company run by Watson and Emelia Williams.

Williams plays the younger sister, Claire, and it’s a superb performance: she’s a convincing, over-played seductress when pretending to be the mistress, and terribly sympathetic when genuinely fearing for her life, after being repeatedly abused by her older sister’s words and actions. It’s Williams’ portrayal of the dichotomy of loving and hating someone at the same time, that shows just how brilliant she is under the intense direction of Watson.

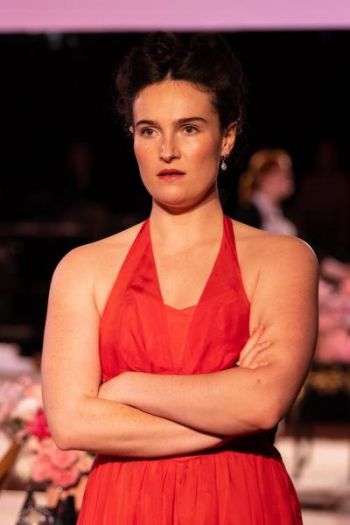

As her older sister, Solange, Virginia Blackwell is extraordinary. She unleashes a threatening thesaurus of insults at her mistress – both to her imagined presence, and to Claire who plays that role in their intimate theatre, then calms to soothe her sibling, her sisterly affection cutting through her barbed words. It’s exhausting to watch her – she never stops – but you dare not avert your eyes. Blackwell’s Solange can be like a furious, manic Villanelle (from TV’s Killing Eve) but she seizes the character of Solange as her own – with ferocity, love, anxiety, and bold sexuality.

This lengthy single-scene play is simply dressed, with a chaise central in the space, a rack of evening wear on each side of the stage, and the entire rear mirrored to reflect the performers – allowing for clever sightlines when the actors are looking away from us, and an opportunity for the sisters (and their mistress) to demonstrate their narcissism.

The audience is looking in – ‘Keep away from the windows!’ warns Solange, every time Claire dares to glance our way – but being opposite the mirrors, they also reflect us, and we’re never just observers in this theatre. Indeed, Solange not only breaks the fourth wall but charges through it, pushing intimidation and seeking validation.

The players are completed by the Mistress, played by Kate Owen: initially, she is the presence of the employer, slowly moving around the edges of the room, always there in the minds of her maids. When she returns home from a night out, her character is larger-than-life, and we see the clear difference between the Mistress as played by her maids and the real thing. She not only knows how to play a powerful woman, as Claire does so well, but she demonstrates that she alone HAS the power. Her mood swings from friendly to officious, but Owen pours patronising so well, always creating clear space between her and the servants.

And it’s here that we see the paradox made clear: the servants play at being her, and they clearly enjoy it, albeit in an abusive way; yet they hate her and what she stands for. They have been seduced by the luxury that the maids clean and tidy – they want rid of the mistress not to redress a power imbalance, but merely to take that power for themselves.

It’s a weakness of the story if you’re looking for justice, but a strength if you want realism. Despite the absurdist and extreme nature of much of the action and dialogue, the underlying fantasy of each maid is to become the person they hate.

Watson’s works are never easily consumed. Unlike some fast-food Fringe fare, his plays are fine-dining that need time to settle, and be digested. Watson’s aromas and flavours are complex, stirring heart and mind: after the initial psycho-sexual sado-masochistic flurry of the opening scenes, I’m breathless with both arousal and fear of the two sisters. Am I laughing because I’m relieved the tension has been released a little, or is it a nervous reaction to my discomfort?

The play is confronting from the very start, and it rarely lets up – Upton’s and Andrews’ translation introduces language not found in Genet’s original, and the initial shock of one too many C-words is quickly blunted, its power lost. Though the power of abuse – verbal, psychological, physical, and sexual – is retained, emphasised, and Genet’s exploration of its connections to one another is wonderfully played out.

If you step back from the exhilarating and exhausting performances, particularly from the two sisters, I wonder how much of the story still stands, and how much of what’s left is ultimately satisfying, frustrating, or just uncomfortable? I couldn’t tell you whether the original 1940s French dialogue left audiences with the same residual emotions – but mine were shellshocked on leaving the theatre, and I was unable to talk about it for a long time. New revelations from the play were still sparking from my mind whilst writing this.

And that’s great theatre, that lives on in your head long after the brilliant immersion into the oppressive world of two sisters working for an upper-class woman. It resonates well with the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ of 2024: we might hate the ultra-rich with a passion, but we still want to be them.

Review by Mark Wickett

Photographer: Philippos Ziakas

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.