Ms Julie Gabler: Trapped

Here is a powerful, engrossing play in which a gripping tension is maintained to the very end. Audiences will recognise elements of Strindberg and Ibsen plays in the title – and then, in the spine of the show itself, Shakespeare’s Othello. But the references - indeed quotations - are there to be questioned and subverted. And as for the extra word in the title ‘Trapped’, the play questions how much its characters – and us – are trapped inside the structures and expectations represented by these literary sources. Sources which we accept as ‘true’ and the way the world is.

Playwright Kathleen Mary Fallon (who is also the producer and director) wants her play to be a warning to the women in the audience. Yes, it is that, but it is more than just that. As well as those literary references, this many layered play is an unflinching depiction of obsessive jealousy and coercive control that here puts racism – that is, an internalised, self-hating racism – at the centre.

But Ms Julie Gabler is also delivered by heightened yet all too credible fine performances from its cast of three... Its three characters are theatre people, saturated in theatrical culture, including the ‘classics’, and so their quotations and banter are not only thematic but credible dialogue – even if they are at times a touch contrived and ‘on the nose’.

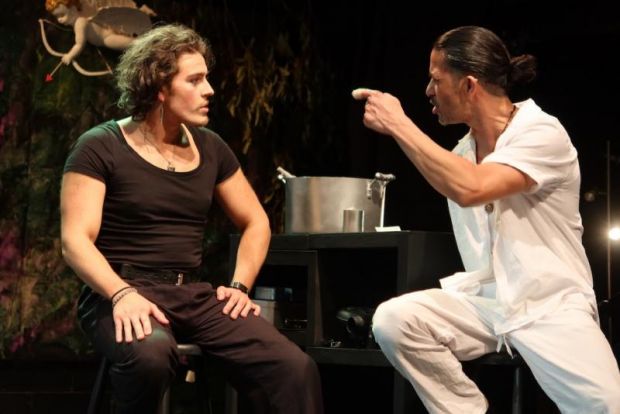

Robert (Sermsah bin Saad) is a deracinated indigenous man, an actor and filmmaker. He is in a fractious, aggressive relationship with white Julie (Ruth Gilmour) also an actor. It’s a relationship that can seem opaque and mysterious to outsiders. But – what can we say? – she loves him. Lately, however, as she tells her friend and confidante Mal (Lenny Cullen Gorman) – also a hopeful actor – that Robert has become occasionally impotent but even more paranoid and obsessively suspicious. He keeps a notebook of all her absences, her comings and goings, and phone calls. Whose is that green car outside?

Robert is an eternally thwarted and ashamed man; he acts out his past traumas and shame on Juile; he’s hypersensitive, bitter, always on edge, always spoiling for a fight, able to turn Julie’s most innocent remarks back against her. And he’s frightening: under the verbal aggression, there is always the threat of violence. In one unforgettable sequence, Robert is cooking rabbit stew. Julie gently reminds him she doesn’t really like rabbit stew... In a flash, he turns that into a racist attack on himself – and he mimes a cute, Disneyfied rabbit, but transforming into a giant, menacing creature from Aboriginal dance. It’s an image that lingers long after this play is over. Julie’s only defence is her own sweet nature, a determination to see the good in him, and a lucky ability to defuse such moments with an ironic swap of apposite theatrical quotations with him.

Robert and Mal are supposedly mates who hug warmly – but they’re also rivals – both wanting to be cast as Othello in a forthcoming production in which Julie will play Desdemona. Mal, meanwhile, has his own constricting backstory. People want him to be and to cast him as indigenous, but in fact he is the descendent of South Sea Island canecutters (Kanakas). Born in Australia, it is background from which he had to escape but which he misses heartbreakingly as he tells us in a beautifully written and performed monologue at the start of Act Two. He too is trapped in a role – but in his case consciously.

Ms Julie Gabler: Trapped is a long play and there is an interval. I sensed an audience suspended and almost resenting the interruption. But such is the outstanding power of the performances and the strength of the text itself that our engagement and the dramatic tension survives over the interval – and over the other elements Fallon adds to her drama: a Voice Over representing Robert’s self-lacerating thoughts, and live music from on-stage musicians. Fraught scenes between Robert and Julie feel a touch repetitious – variations on a theme. Fallon is so driven for us to understand that she is perhaps over-emphatic and over-enhances her text.

But what resonates as we leave the theatre is the performances – Sermsah bin Saad in particular. Only at the end, is what we suspected and hoped for revealed and confirmed. Shakespeare, Ibsen and Strindberg are overturned – but as much as that might be a victory, we are left with the pathos of Robert, stranded in his violence and self-pity. All that we’ve seen and felt is happening now and will happen again.

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.