The Father

The great risk French playwright Florian Zeller takes with The Father is to tell its story from inside the mind of an elderly man who is losing his mind. ‘Dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer’s’ are not mentioned, but we nowadays, we know all too well.

What we see on stage may or may not be ‘true’, but it is as André (John Bell), a retired engineer, sees it and attempts desperately to understand it. Via his fractured apprehension, identities change and the past keep changing, and where he’s sure he is, in fact, is not there at all – or so he’s told. He’s bewildered – though he strives to hide it by being irritable and ‘forceful. He is (literally) ‘losing the plot’ – and he tries desperately to resist. He becomes fearful: no one is talking any sense. Are they trying to deceive him? At first, for us, the audience, this is amusing: he’s just a cantankerous, forgetful old man, but as inexplicable things pile up and he becomes afraid, the laughter fades away.

Is André in his own flat, in Paris, which he flatly refuses to leave, or is he in his daughter Anne’s flat? Anne (Anita Hegh) seems to be trying to look after him, including getting him a new carer since he keeps driving them away. She seems to love him (there’s more warmth in the performance than in the words), but he says he prefers her sister Elise (whom we begin to suspect is not around any more) – and he is very rude to and about Anne. She may or may not be moving to London, and she may (at one time?) have had a husband called Pierre (Marco Chiappi), but then there’s this other, smiling fellow (Glen Hazeldine) who claims that he’s Pierre – and there’s a blonde woman (Natasha Herbert) who says, with complete certainty, that she’s Anne… But then Pierre and, separately, the man who says he’s Pierre become shockingly violent and ask André how long he’s going to hang around, getting on everyone’s tits. Did that really happen? Twice? Short, sharp scenes are divided by the blackest of blackouts and with a new scene can come a change of time, of people, of furniture – or no furniture.

Is André in his own flat, in Paris, which he flatly refuses to leave, or is he in his daughter Anne’s flat? Anne (Anita Hegh) seems to be trying to look after him, including getting him a new carer since he keeps driving them away. She seems to love him (there’s more warmth in the performance than in the words), but he says he prefers her sister Elise (whom we begin to suspect is not around any more) – and he is very rude to and about Anne. She may or may not be moving to London, and she may (at one time?) have had a husband called Pierre (Marco Chiappi), but then there’s this other, smiling fellow (Glen Hazeldine) who claims that he’s Pierre – and there’s a blonde woman (Natasha Herbert) who says, with complete certainty, that she’s Anne… But then Pierre and, separately, the man who says he’s Pierre become shockingly violent and ask André how long he’s going to hang around, getting on everyone’s tits. Did that really happen? Twice? Short, sharp scenes are divided by the blackest of blackouts and with a new scene can come a change of time, of people, of furniture – or no furniture.

Alicia Clements’ set design is risky too. It’s naturalistic: a shabby but convincing old-fashioned Paris apartment with rather ill-matched furniture. So, when André is told, ‘No, Dad, this isn’t your flat; we moved you in here…’, the confusion mounts because it looks just the same – except that now there’s just a couch – or nothing. At the end, when he is definitely not at his flat, or Anne’s, does he think he is?

The Father is not quite a ‘puzzle play’, but we must twig at some point that there is a puzzle, but one with no answer: we are simply experiencing André’s world as he does. If we were to source all his disordered memories and reorder them, there would be a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. But here, not in that order. His misinterpretations and misapprehensions do have a certain logic to them, but it’s only revealed in the play’s final scenes and it doesn’t quite bear too close a scrutiny.

I’ve remarked before that you cannot have a mad person as a protagonist, but in this case, André is not mad; he is, as it were, the remains of a man who could be one of us. Our sympathy is increased by the fact that the other characters react to him in ‘normal’ ways – that is, in ways one might react to someone who’s behaving like André – with insouciance, exasperation, indifference, ‘patience’ or impatience. (No one, however, acts or reacts as if they recognised that ‘this is a man with dementia’ – which is somewhat of a contrivance.)

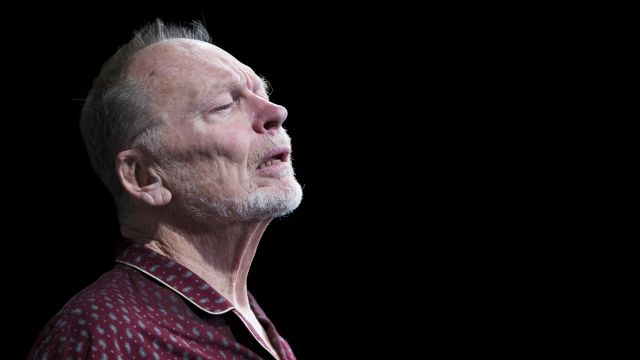

A powerful element of this production is, unavoidably, John Bell’s stage presence, bolstered by his years of experience, in contrast to the role he plays here: a man who is losing his mind. But when André claims he is intelligent (among other, clearly ridiculous claims) we believe he was. When Laura, a carer (Faustina Agolley) finds him ‘charming’, and he agrees that he is, we believe that too. When she treats him like a child, we are outraged on his behalf. Were Mr Bell merely ‘likeable’ or ‘interesting’ or ‘a good actor’, there would be pathos, but this performance goes beyond that. He is the focus and he carries the play. At the climax, when André loses the battle he has been fighting the whole play, it is tragic.

A powerful element of this production is, unavoidably, John Bell’s stage presence, bolstered by his years of experience, in contrast to the role he plays here: a man who is losing his mind. But when André claims he is intelligent (among other, clearly ridiculous claims) we believe he was. When Laura, a carer (Faustina Agolley) finds him ‘charming’, and he agrees that he is, we believe that too. When she treats him like a child, we are outraged on his behalf. Were Mr Bell merely ‘likeable’ or ‘interesting’ or ‘a good actor’, there would be pathos, but this performance goes beyond that. He is the focus and he carries the play. At the climax, when André loses the battle he has been fighting the whole play, it is tragic.

If, on reflection, The Father seems just that bit tricksy, even gimmicky, and rather lacking in development, it does succeed (as far as we know) in making us see the world as someone with dementia might and it is enriched by this excellent cast. Director Damien Ryan, an actor himself, draws detailed performances from his cast with nice judgement as to when to play it straight and when to take a sudden turn into the bizarre. This is an award-winning play and it cannot be simply because it has an ‘important’ subject. It’s not a great play, but it is written with insight and skill and its shading from comedy to fear and despair holds the audience for all its 90 minutes.

Michael Brindley

Images: John Bell, Faustina Agolley, and Anita Hegh & John Bell. Photographer: Philip Erbacher.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.