Vasily Petrenko Conducts The Rite Of Spring

Image: Vasily Petrenko. Photographer: Mark McNulty

Nobody really knows why the famous premiere of Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring caused such a riot at Ballet Russes in Paris in 1913. One scholar says Stravinsky spent his long life telling lies about it.

They were rioting from the start, as that first solo bassoon began such a yearning Lithuanian folk song. Some suggest it was Nijinsky’s monotonous choreography, or the discordant explosions of instruments, colliding with each other in different keys and rhythms, creating a thrilling modern music familiar to us now through jazz and cinema – but not in 1913.

The most likely offence was Stravinsky’s terrifying story of a pastoral community from Pagan Russia, and his unrelenting liturgical sequencing as elders gathered for the sacrifice of a young girl left to dance herself to death. The horns and woodwinds alternative as rival tribes, quieter reflective periods come, then give way again to an orgiastic thrust and the climax which is savage. It’s scary stuff.

The face and hands of Russian-British conductor Vasily Petrenko express the detail and sometime delicacy of the score, and with his agile body he keeps (almost) balanced this full commotion of instruments. It’s a joy to watch him and each section of the vast SSO from above as they synchronise and individually build the hysteria. Without the ballet the story is unseen but the ghost of it is so vivid throughout the score and in the musical clarity of this performance.

The first half of this SSO Concert features a more modest, less demanding work, Camille Saint-Saens’ Cello Concerto No.1 with German-Canadian cellist, Johannes Moser.

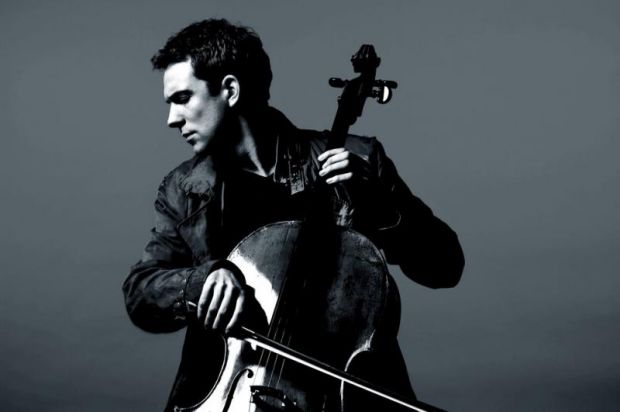

Image: Johannes Moser. (c) Manfred Esser - Haenssler Classic

Image: Johannes Moser. (c) Manfred Esser - Haenssler Classic

Giving room to the soloist, the orchestra’s size is much reduced and Petrenko’s conducting is noticeably softer and discreet, but at first Moser’s cello still seems over-powered. He fully dances to the fore in the minuet-like second movement, beautifully conversing with the woodwinds, and leads to a virtuosic final movement with high harmonics.

More magical for me was Moser’s beguiling encore with the SSO cellists, playing Sarabande from Edmund Grieg’s Holberg Suite.

Photographer: Daniel Boud.

The concert opened with another commission in the SSO’s 50 Fanfares Project, the premiere of Nineteen Seventy-Three by Elizabeth Younan. This was less a heralding fanfare than a major albeit abbreviated symphony, one rich in sudden orchestral rises and falls and, indeed, a herald of Stravinsky to come. And of course it’s a big fanfare. Younan dedicated Nineteen Seventy-Three to the collective sacrifice and effort to build the Sydney Opera House, completed that year.

Martin Portus

Photographer: Daniel Boud.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.