work.txt

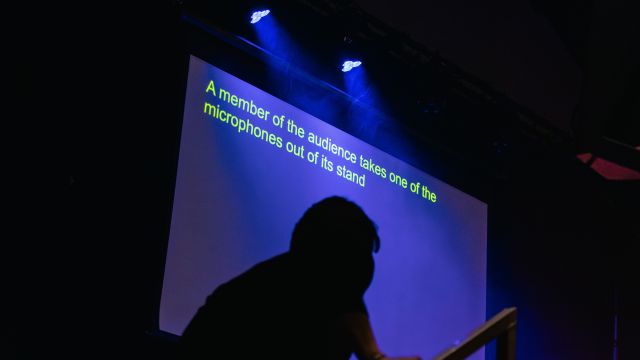

The stage looks as if something was interrupted. There are two microphones on stands, each with headphones; there’s a printer, and a jumbled pile of wooden blocks. Above the stage there’s a large screen. There are no actors. We, the audience, are the actors, but the text (questions and instructions) is supplied – and it begins on the big screen...

We are divided into categories, including who got up early, who got up late, who slept badly, who earns more than $90,000 p.a., those who’d rather be somewhere else, or in another, more traditional show, but nevertheless a story begins – the story of a day in the working life of a city. That’s what this show is about: work. And electronic text. And images.

(Apologies if I get the steps in the wrong order. As long as you get the idea.)

Somebody is asked to ask who is in charge. We’re told no one is in charge. No one in charge is true to the extent that we can ignore the questions and commands projected on the screen, but we don’t because – at this stage – we are curious about where this going, what will happen next. Of course, Nathan Ellis, who concocted all this, is in charge. That’s the central irony of work.txt, a show about work. No one is in charge – perhaps no one needs to be in charge - but we are all following orders, enmeshed in and therefore supporting and endorsing the systems that make up most folks’ work.

We’re told in a program note that work.txt dissects ‘productivity, technology, group think, classism, the corporate exploitation of art, and the nature of humans to achieve for achievement’s sake.’ Yes, that is the playwright’s intention, but the show relies on the audience – to perform and to understand.

Two volunteers go up on stage, tasked with moving a wooden block to anywhere they like on the stage. Then we are, all of us, invited up on stage to arrange those wooden blocks anywhere we like. Curiously, people build structures – squares, towers, arches... When we return to our seats, the screen tells us we have made a city. Now we need a character – that is, another volunteer from the audience.

This volunteer chooses a name: ‘Penelope’. (On another night, the volunteer could choose something else.) And from here the story unfolds. Penelope is ‘creative’: she writes social media content for various websites. But on this day she gets bored or tired or defeated and she lies down on the marble floor of her workplace’s foyer. This act of rebellion – if that’s what it is – invites speculation but no one asks Penelope why she’s doing this, or even if she’s all right. It is the only act of resistance in the whole piece.

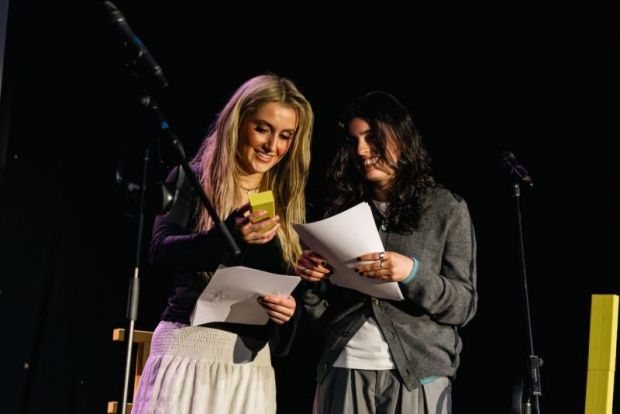

Two more volunteers come onto the stage and collect scripts from the printer. They read their scripts into the microphones. Although we learn their ‘characters’ have never spoken before, they ‘perform’ what they come to realise is a ‘water cooler’ discussion...

Photographs of prone Penelope go viral, go world-wide – and people (more prescripted volunteers) begin to speculate what uses can be made of them. Is the image of Penelope a work of art for instance?

As ‘entertainment’ the texts on screen are witty but the three pre-scripted two hander scenes are deliberately banal (to make point). Much depends on the quality of the volunteers’ ‘performance’ and the willingness of the audience to respond to on-screen questions and commands in a clear and lively manner. On our night, there was some resistance and occasional reticent mumbling – especially when the performers had to repeat text fed to them via the headphones.

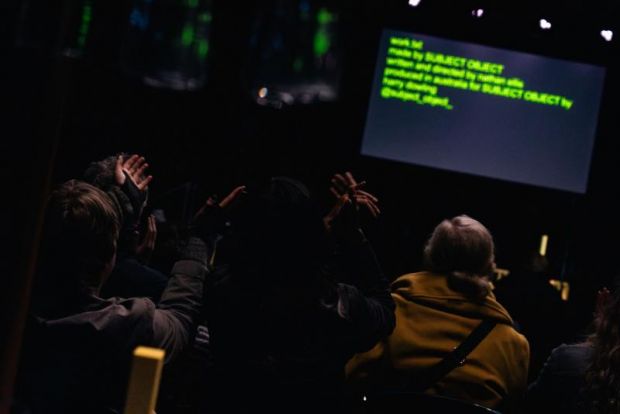

This piece of anti-theatre theatre has been met with wide acclaim and awards. David Byrne at London’s Royal Court even wondered whether SUBJECT OBJECT productions are ‘the future of theatre’. I hope not. I wonder if the acclaim is due more to an understanding of playwright Nathan Ellis’ subversive intentions and originality rather than for the work itself. What happens on stage generates a certain tension, as noted, about where it’s going and what will happen next, but that doesn’t entirely prevent longueurs that test our patience. Most of the audience will, I think, recognise a satirical version of their working lives depicted here – mundane and meaningless. Unfortunately, we might also have to admit that soulless, deadening work might be a sine qua non - necessary to ensure people get paid, can go shopping, go on holidays and watch Netflix. You might blame ‘capitalism’, if you like, but to think things are or could be different under socialism is surely an illusion – and I think Ellis knows this perfectly well.

What’s fascinating about work.txt and makes it very much worth seeing is the way it slyly plays with theatrical forms and audience expectations while questioning the systems and the technology that trap us all – even if it doesn’t do that at any great depth. We work for systems that don’t work for us - but their maintenance is the priority we all accept.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Liv Morison

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.