Worstward Ho

Worstward Ho is not a play, it is ‘prose’ – that is, not written in 1981 as a play to be performed by an actor. Robert Meldrum and Richard Murphet thought otherwise and over three years, they have been ‘decoding’ (Murphet’s term) it so as to render Beckett’s difficult text clear in performance – but without diminishing its difficulty.

Because it is difficult. It is a one-hour monologue by one man. There is no story. There is no plot. Worstward Ho is a depiction of man intensely thinking – thinking as one thinks should one think as this man does and about what this man thinks. That is, thinks – not remembers or reminisces - although any thinking by a human being will be informed by life experience, an individual imagination and shaped by that person’s fears and values. Here, overall, is an awareness of ‘the void’. Prayer is mentioned, but there is no response.

The text, however, is not ‘logical’; it moves forward but it also moves back – but when it moves back it may discard its first meaning – the word ‘No’ occurs over and over – or it discovers new meaning. It is necessarily repetitious – or seems so but only because of the thinker’s pursuit not just of meaning but meaning as a reason to go on. The first word spoken is, ‘On.’ That is, how to go on. A central and crucial series of lines is the familiar:

Already tried

Already failed

No matter

Try again

Fail again

Fail better

There is a dogged determination to that. (Those lines are usually ‘Try again/Fail again’, but ‘Already tried’ – Déjà essayé - seems to me even more courageous.) But the text is not always necessarily grammatical as that. It plays with words and word associations. There are Beckett-ian puns. (E.g. the title of the work.) There are flashes of vivid visual images that illuminate the thinking by metaphor – the ‘dim void’, a skull, a fixed stare, clenched eyes, an old man with a small child walking hand in hand, plodding, in the dim void, kneeling, barefoot, a supplicant …

It would be near impossible to summarise beyond this: a solitary man (Meldrum) wrestles in his thinking about teleological and existential questions. Given the lack of ‘story’, the (only apparent) lack of logic and grammar, it is an astonishing achievement by Meldrum to retain and deliver this text so forcefully, intensely and, yes, as engagingly as he does. In lesser hands, a spoken rendering of this text could not work, could not communicate.

The process, so Murphet told me, began with Meldrum ‘scanning’ every line, finding they are all iambic pentameters (the natural rhythm of human speech) and then committing each to memory – and finding the emotion appropriate to each.

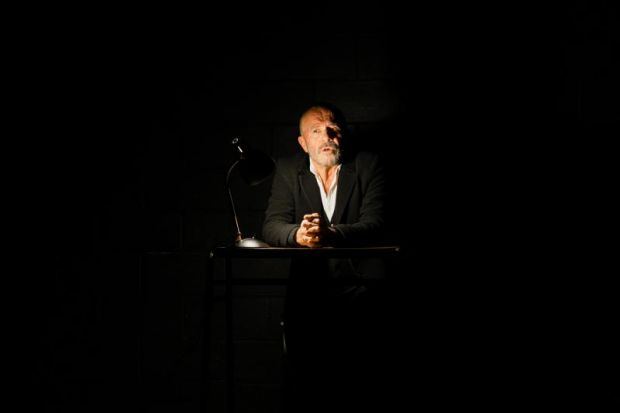

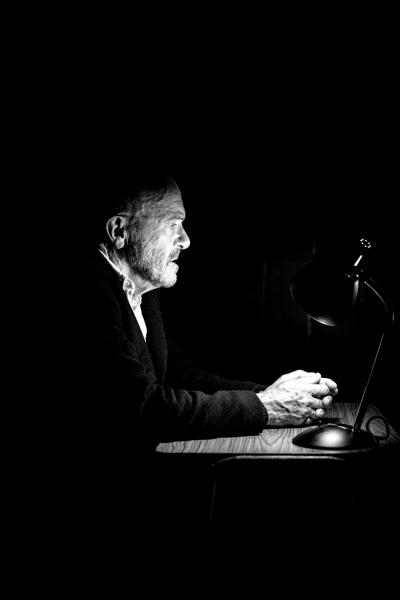

In performance, Meldrum is one man in a black frock coat, alone on a stage bare except for a desk and chair, with lamp, a bench and an armchair. He walks about, squats, presses against the black, bare back wall, or moves among these props, sometimes briskly, sometimes slowly – or wearily. These movements are not arbitrary: they reflect the movements of his thought. A new thought, an old thought, a dead end, a ‘try again, fail again…’

The moves are given resonance by Murphet’s lighting design. Seated at the desk, Meldrum is the traditional image of the scholar thinker, but his thought is too restless, too urgent, too disordered to stay there. At times he is in total darkness, then in a spot, then cross-lit, the lighting warm or freezing. He comes toward us as if to be with us… and then disappears, as it were, back into his thinking, back into the ‘dim void’. We care about him – and then we can only witness his struggle.

Worstward Ho is not an ‘easy work’; it requires intense focus, attention, and concentration to follow this man’s thinking and to discover its coherence. Yes, maybe one is limp with mental exhaustion by the end (or earlier), but one is rewarded. Yes, we may remember Meldrum’s performance longer than we remember what Beckett is showing us, but Meldrum’s (and Murphet’s and producer Matthew Connell’s) devotion to presenting this gnarly, jagged text to us is truly impressive, and truly moving.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Chelsea Neate

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.