Kate Mulvany’s Joy, Magic and Darkness

Image: Kate Mulvany in The Literati (Photographer: Daniel Boud).

As Kate Mulvany perfected her new work to open Sydney’s renovated Wharf Theatre, the celebrated writer and actor shared with Martin Portus her vivacious signature of joy, magic and darkness – and a remarkable career lived in pain.

Kate Mulvany was raised in the windy, if story-rich, port of Geraldton, north of Perth, but spent most of her first decade in the hospital. The little three-year-old was carrying a tumour the size of a football, and to remove it, they severed ribs, cut out organs and glands and blasted her with so much radiotherapy that her spinal cord is atrophied and her vertebrae still continue to shatter.

Lying there in the oncology ward, where some kids would just disappear, she discovered books. She consumed fairy tales of magical exploration and possibility, playful but with an uncompromising darkness, all of which power her writing today. And as a teenager, she read Playing Beatie Bow.

Image: Playing Beatie Bow - Sydney Theatre Company (Photographer: Daniel Boud).

Her adaptation of Ruth Park’s novel re-opened the Sydney Theatre Company’s Wharf Theatre in February after years of renovation. It’s an apt story to blow away the COVID pall and open our eyes to the world outside. It’s the modern tale of a troubled young girl who finds meaning and connection by following Beatie Bow back through the lanes and lives of The Rocks in 1873, right there on the Wharf’s very doorstep.

The STC’s Kip Williams directed, as he did Mulvany’s epic adaptation of Ruth Park’s trilogy The Harp of the South in 2018; this centred on Sydney’s then working class suburb of Surry Hills. With 18 actors playing characters spanning decades, Mulvany spent nearly three years translating the trilogy’s 900 pages into an astonishing six hours of theatre about love and grief, families and communities struggling against development. Her compass point?

“It’s to look up,” says Kate. “It’s for theatre audiences to look up and see the history around them that is often still engraved on the tops of buildings and see Sydney’s shifting light. Sydney itself was, and is, a fascinating character.”

Image: Playing Beatie Bow - Sydney Theatre Company (Photographer: Daniel Boud).

She’s cautious to avoid “poverty porn” but Mulvany has, unlike some young playwrights with something to say, always been comfortable writing in the Australian working vernacular – even with an occasional flowering of fairy storytelling.

“Working class, country dialogue and accents is my forte, since that’s where I came from.”

She can also turn Gothic with shocking theatricality, as she did in her first play, when a tomboy teenager at Geraldton High. Rosemary Lamb showed a wife cooking up her husband’s mistress and feeding her to him!

One favourite early play, Storytime, at Sydney’s Old Fitz in 2004, partly drew on her own family. Two criminals in a max security cell entertain each other telling dark Gothic tales. A part inspiration for the language was watching her uncles when she and her father (Danny) visited his home in Nottingham, England.

“I got a bit of an understanding into their dealings, their ‘bits and bobs’ as they called it; it was mostly just black-market Viagra, illegal steroids, but there was a bit of standover as well.”

Storytime was the antecedent to her award-winning autobiographical play The Seed, staged at Belvoir and around Australia from 2007. It grew from hearing that her childhood cancer had left her unable to have children, and her anger and growing militancy about how she had been likely poisoned by the defoliating dioxin Agent Orange, which her father had been exposed to while fighting in Vietnam. Danny had been conscripted soon after he migrated to Western Australia as a Ten Pound Pom.

“I was one of the Children of the Mist, as they’re often called,” says Kate. “He tried not to go but he thought later that he could have been more belligerent about what happened, so I think there was this level of guilt, real deep loathing, anger and bitterness, and in my Mum to some extent. So as a child having the disease, I had it too – I thought it was my fault.”

The Seed lays out this story, dramatizing three Mulvany generations as Rose/Kate, a journalist, and Danny visit his own estranged father in Nottingham, who’s a bullying IRA sympathiser with a criminal charm. The play’s considerable humour has equal touches of Irish, British and Australian.

Mulvany was reluctant to play Rose, but the director, Iain Sinclair, convinced her. “They’re your scars – show them,” he said.

Kate’s parents came to the Belvoir premiere along with dozens of other veterans.

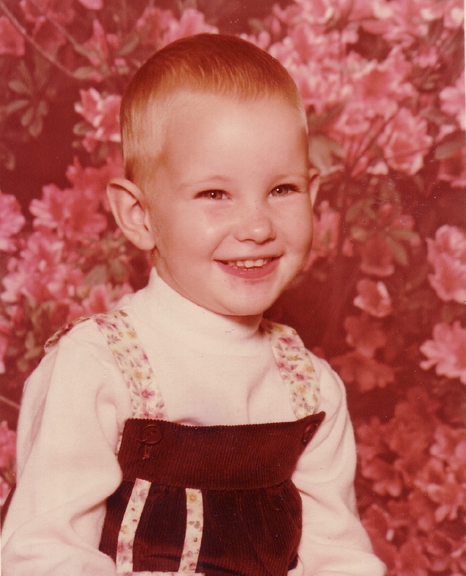

Image: Young Kate Mulvany.

Image: Young Kate Mulvany.

“They hadn’t read the play - they trusted me; I offered it to them to read because there’s a lot of eggshells and cliches around veteran stories.”

She saw her Dad after in the foyer, for the first time truly happy, proud, head high, now with her “a different ally in a different kind of war.”

As Ambassador for MiVAC – Mines, Victim and Clearance - Kate later travelled with her father to Vietnam and Laos, along with her husband, the actor Hamish Michael. Danny Mulvany died in 2017 of a suspected Agent Orange cancer. It was in the same week Kate opened in what is arguably her greatest role, as Richard III, her own disability for the first time fully laid bare to play the ‘crippled’ king.

Image: The Seed at Belvoir. (Photographer: Heidrun Lohr).

Image: The Seed at Belvoir. (Photographer: Heidrun Lohr).

“My Dad was my best friend, my ally and my muse,” she says.

Kate Mulvany suffered another profound loss in 2008 with the suicide of the well-known TV actor Mark Priestley, then in the top rating hospital series All Saints. She’s still haunted by memories of hospital staff asking for his autograph, some even disbelieving the actor’s pleas for help, and then the media intrusion. She suffered a long depression and anxiety, didn’t act for nearly three years, but suicide and mental health continues to feature in her plays and her public advocacy.

“There was a lot of suicide in my community around me growing up and again that was due to the absence of mental health facilities. It was in the first play I wrote after Mark with The Web; it’s a very raw story about a woman who has just lost her partner to suicide and has to deal with the trauma and getting on with life.”

Another quality in Mulvany’s work is storytelling, often set in country towns and told through the eyes of young males. The Web is about social isolation in a regional town, cyberspace crime and an ill-fated friendship between two male teenagers. The Danger Age shows how World War II might threaten a country town, as seen through the imagination and innocence of a ten-year-old boy.

“I learnt that the most dangerous age for a male is at ten – the time we take risks – it’s the Danger Age!

“I think my ten-year-old boys are an amalgamation of myself, a little ten-year-old tomboy as I was just after I was cleared of cancer. And I got up to mischief because I was finally free! I idolised my father and I grew up in a very masculine community. So, in a way these boys are me and the ones I grew with and love, and who became fine young men.

Image: Young Kate Mulvany, with her dad Danny.

Image: Young Kate Mulvany, with her dad Danny.

“And I often set my plays in country towns or small communities because I think they’re the perfect petri dish or microcosm of the bigger world.”

In the same tradition is Mulvany’s acclaimed adaptation of Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones, as narrated by nerdy young Charlie, during the Vietnam War, in a country town thriller around the mysterious Aboriginal boy, Jasper.

While one focus may be on the juvenile male, Mulvany ensures her plays and adaptations expand the women in the story into meaty roles she’d be attracted to play. It’s what you’d except from a writer known, especially recently with works like The Mares, for her feminist assertions … let alone as an actor who’s excelled in new gender-blind role-playing, notably in Julius Caesar, Richard III and An Enemy of the People.

Medea (2012) was a masterpiece of these different sensibilities. With two boys who’d never performed before, and her frequent collaborator, director Anne-Louise Sarks, Mulvany developed the story of Jason and the traumatised Medea through the eyes of her two young sons playing and bantering in their bedroom.

Image: Rory Potter, Blazey Best and Joseph Kelly in Medea. (Photographer: Heidrun Lohr).

Their games show they grasp some of the adult issues beyond the door; Medea enters rarely, finally lingering to feed them poisoned cordials. It’s horror theatre and, oddly, we almost understand the abused Medea. Medea won success in five overseas productions but – in a familiar provincial crime of Australian theatre – is another fine play barely staged beyond its origin city.

Euripides of course is much too dead to take issue with anything done to his famous story. And so too is Friedrich Schiller, whose Mary Stuart Mulvany adapted for the STC two centuries after he wrote it. She was the first woman in a long line of males who’ve adapted it – and was staggered at all the information and revelation about the two feuding queens left out of the original play.

“The whole play is about men moving the women, the queens, around as pawns, and I wanted to shift that to having the women move the men, the ‘obscure men’ as they’re called in one contemporary document.

“Adaptations usually start with talking to the author, if possible, in the process of babysitting their child and being very grateful for what they’ve created, but leaving room for your own contribution. I’ve never met a writer or their estate which hasn’t let me do that. But I ask them to tell me everything they think I need to know and their perspective on what they think this is about. It’s really important that all of us – and the creatives – have a piece of the jigsaw, and that includes the audience as well.”

Mulvany’s journey to adapt Kit Williams’ celestial fairy tale Masquerade – for a three city tour of Australia – had her flying to England, at his request, and knocking on his cottage door in Stroud exactly one year after Mark Priestley’s death. This simple love story between the moon and the sun had entranced young Kate back in that oncology ward. Williams gave his permission but only if she included her own story.

“That, out of all my plays, was where real life and fiction melded in the best of ways.”

One of Kate’s godmothers, Tessa, a local farmer’s wife, first brought her this fantastical riddle of the lost amulet. Tessa later took her own life but she lives on in Masquerade as the mother. One of Tessa’s sons, Joe – young Kate’s best friend – is reborn as the boy in that oncology ward, amalgamated with kids in the real ward who Kate befriended and who never left it alive. In Masquerade Joe travels with his Mum in search of the amulet, but he dies in the end.

Image: Masquerade (Photographer: Brett Boardman).

Image: Masquerade (Photographer: Brett Boardman).

Mulvany doesn’t pull punches – and certainly not for kids.

Her career as an actor has rocketed since playing the Helpmann Award-winning role of Richard III in 2017.

“Through all this time my spine has been gradually crumbling beneath my body and skin. I wasn’t aware I could use the word disability; I didn’t know how to claim that this far in, because I’d been in hiding. For fear of people not hiring me, I didn’t mention my chronic pain.”

“But I was encouraged by seeing those bones dug up (in a Leicester car park in 2013) – where everyone could see what Richard lived with every day – with such severe scoliosis.”

She understood why Richard, in battle, so desperately cried for his horse – for its supportive high arching saddle – and why he turned to red wine to dull the pain. And so, in the first week of the Bell Shakespeare rehearsals, Mulvany stripped off her shirt and showed the cast her condition - how her body lands when released.

“The moment I came out of my spinal closet, my Richard closet, life got a lot easier.”

She won another Helpmann for her solo role in the British audience participation play Every Brilliant Thing, rejecting suicide for the simple joys of living. It was cathartic, life-affirming theatre, but tough.

Image: Kate Mulvany in Every Brilliant Thing at Belvoir (Photographer: Brett Boardman).

Image: Kate Mulvany in Every Brilliant Thing at Belvoir (Photographer: Brett Boardman).

“I never enjoyed performing that one as much as it looked because you had to be so careful with its impact. It would be rare to have a group of 300 people who haven’t been through that experience in some way.”

Mulvany is perhaps on safer ground now, playing in the Amazon Prime series Hunters, opposite Al Pacino, as the Nazi hunting nun and ex-spy Sister Harriet.

Kate Mulvany spoke to Martin Portus for the State Library of NSW oral history collection on leaders in the performing arts. The full interview will be available soon on the Library’s website.

Purchase Kate Mulvany's scripts at Stage Whispers' Books.

Image: Kate Mulvany with Al Pacino in Hunters.

If you or anyone you know needs help:

Lifeline on 13 11 14

Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636