The Power of Sound

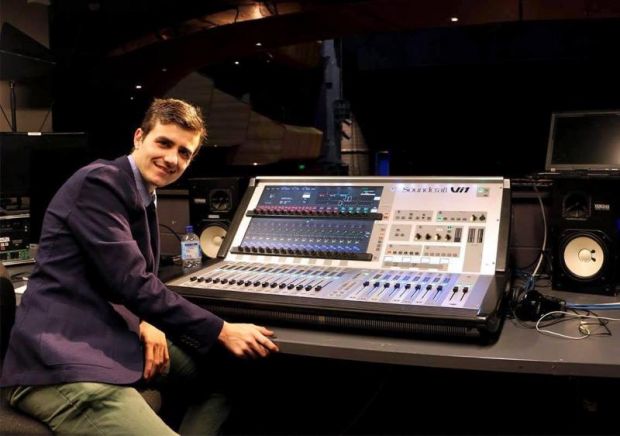

Image: Steve Francis. Photographer: Daniel Boud.

Beth Keehn speaks to four of our award-winning sound designers.

Sound design is like an invisible character in a stage play – it can tell so much of the story, yet you might only notice it when it makes a fumble, staggers into a performer, or hits a bad note on the piano!

A fascinating role, sound design is tackled by intrepid practitioners who often have to compose music as well. Interestingly, the four sound designers I spoke to recently came to the role in different ways – but all share a passion for sound and music, and working with directors, cast and crew to help them use the unique sonic palette to bring a play to life in engaging and innovative ways.

Steve Francis has worked for Australia’s leading State and independent theatre companies including Bangara Dance Theatre, as well as in film and television.

“The key to theatre sound and music is knowing when to stay out of the way,” he said.

As a guitarist and sound designer, Steve has an innate understanding of how sound can complement other storytelling elements.

“When I’m composing for a film, I always chat to the sound team because it’s good to know what they’re bringing to a particular scene. You don’t want to be telling the same story or stepping on each other’s areas. The key to theatre sound and music is knowing when to stay out of the way.

“Sometimes the playwright will have a distinctive idea for sound. In his play Appropriate, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins mentions cicadas, and Director Wesley Enoch (Sydney Theatre Company) had specific ideas about using them as a prevalent noise throughout the play. To add dynamic, I incorporated music into the sound effect.”

Image: Steve Francis. Photographer: Daniel Boud.

Image: Steve Francis. Photographer: Daniel Boud.

For Bangara Dance Theatre’s SandSong, Steve worked in the opposite way – adding sound to music.

“We took a trip to the Kimberley to document some traditional songs, but I also recorded atmospheres and natural sounds to add to the score – sometimes the non-musical aspects can ground you in the play’s particular world."

Steve is starting work soon with Director Sam Strong on Boy Swallows Universe for Queensland Theatre (QT).

“I will set up my studio in a friend’s garage space and I’ll stay for the 5-week rehearsal. I usually take in some schematic ideas – a mood board version of the music – but then I’ll respond to what Sam’s doing with the actors. I love being around rehearsals. Hearing the actors perform is an inspiration.

“Also, we’ll chat about the design – the set design by Renée Mulder is extraordinary, with a large video element. That informs my world. Boy Swallows Universe has some very bold moments and I imagine that we’ll have some very bold storytelling within the sound design as well.”

Image: Steve Francis, Bennelong, Bangarra 2017. Photographer: TIffany Parker

Anna Whitaker works as a composer, sound designer and audio engineer.

“There are so many different elements – that’s what I love about the role!” she said.

Anna thrives on collaboration and her work is multi-faceted across composition and sound. Her background was in classical music and violin, but it was while studying a Bachelor of Music Technology at the Queensland Conservatorium that she learned about studio production, mixing and live sound.

“As a composer and musician, it has been so useful having developed those skills for sound design in theatre. Having that understanding of the technical side has been incredibly helpful in workflow and efficiency, especially when you often have short periods to write a lot of music, or a client wants an orchestral piece recorded.

“Sometimes you wear a lot of hats – you have the creative process with writing the music, and then you have to mix it and master it all, as well as the sound design, making sure it all sounds unified and together, and then programming it all in QLab. I love getting in the space early, meeting the director and the cast, talking with the artists about the emotions, the feeling of the world that we are creating and get an idea of what that sounds like.

“I love the variety of doing technical work, sound design, composition and installations.”

In 2019 Anna shared a Matilda Award for Best Sound Design/Composition as Associate Designer with Luke Smiles for Throttle – an immersive ‘B-Grade Horror’ dance-theatre piece by The Farm, set in a drive-in theatre space.

“(For)Throttle the audience sat in their own cars and watched it in a field. The sound was all heard through the car stereo system via a dedicated radio station. There was dialogue, atmos, sound effects – it was quite intense.

“I love collaboration and the variety of technical work, sound design, composition and installations because I want to be open to all areas of sound. I enjoy the constant stimulation and getting to work on so many different types of projects.”

Julian Starr works in Australia and London as a sound designer and composer in venues ranging from the West End to castles.

“My role is to collaborate with the director and creative team to deliver the best utilisation of sound and music,” he said.

“When I decided to work in the theatre, I wanted to become a stage manager. But, while working with Sarah Goodes at NIDA I realised I wanted to get more involved in music and sound. At the end of my third year I was awarded a scholarship that took me to the UK, where I worked with sound designer Paul Arditti at the National Theatre, and on the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo, and Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein.

“My role is to collaborate with the director and creative team to ensure creative problem-solving and deliver the best utilisation of sound and music to support the show’s narrative, character development and other design elements as a whole. In 2019, I designed and composed for 25 shows. Then – like so many others – I lost a whole year of work in one day. Back in Australia, director Heather Fairbairn reached out as she’d just started the Hive Collective at Metro Arts. When she gave me the script for Elektra/Orestes, I jumped at the opportunity.

“A month before rehearsals, Heather visited my studio and gave me three words: ‘dark, distorted and twisted’: I said ‘I can do that!’ The play is in two settings and the second half goes back in time – we used sound to set up the tension for what is about to happen. I like to bring something new and interesting to a show, and I had just received a custom-made synth from Resonant Garden in LA, so many of the sounds and musical textures I created for Elektra/Orestes were heard by Brisbane audiences for the first time.

“You do have to be flexible because if the show’s changing, you have to adapt with the show and other creators. For example, I worked on a devised show called Scrounger at the Finborough in early 2020 and director, Lily McLeish, played me a film soundtrack that sent me in a new direction. When that happens and a director likes a key element, then I know how to do the show. I usually lock myself away for 72 hours and complete the score - the ideas – you just have to work hard and fast to deliver.”

Where to hear Julian’s work:

Late Night Staring at High Res Pixels – Finborough Theatre online – finboroughtheatre.co.uk

Tony Brumpton has regularly worked for Queensland Theatre (QT) , Black Swan and Dead Puppet Society (The Wider Earth, Laser Beak Man).

“I am actually thinking of the audience and what their sonic journey is going to be,” he said.

Some sound designers start from a musical background, but it was Tony’s technical skills that got him his first gig. It was for QT – Absurd Person Singular by Alan Ayckbourn – an FX-laden script. Tony stepped up and found his route to sound design. He is currently back at QT and in rehearsals for Taming of the Shrew.

“Shrew is an unusual sound design because director Damien Ryan has reimagined Shakespeare’s play in a new time period – so we’ve been looking at music and sound that fits. We had meetings a couple of months ago about what the concepts were. On other shows, we can start years in advance. We’ve been working on Dead Puppet Society’s Ishmael for nearly three years – partly due to the lockdown, but also because it’s incredibly complex and we have to build the sounds from scratch.”

In 2017 Tony flew to London to help premiere Wider Earth as the first theatrical show to grace the heritage-listed Natural History Museum. The team had to build a new space to host the show in just six weeks.

“With puppets, it’s a more intensive process because you have to develop the sound design as the script is being developed – coming up with an ‘aural stenography’ – the whole world, rather than just separate sound and music. I am actually thinking of the audience and what their sonic journey is going to be.

“For Dead Puppets, the musicians are usually recorded first and then I come in. For other shows I tend to take on the whole thing – writing music, finding soundscapes. And, in theatre (unlike film) I am often designing the speaker system, making sure it suits the venue and is immersing the audience in the right way.”

Tony juggles his time between hands-on theatre work and lecturing at QUT.

“I choose theatre projects that have something technically or acoustically challenging, or that support culturally important stories – for example, City of Gold or Black Diggers. Academics should have some idea of practice – getting hands-on and being active and involved – so I can inform the next generation about the issues they will be working with.

“With every project, I try to pick one new thing to try. I also value the people you get to meet – it’s never like showing up to an office job – you still spend a lot of time looking at spreadsheets, but different ones each gig!”